My husband, Neil, and I were staying at our summer house in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. I love that house because it’s a rustic cabin on a wooded lake but also a short walk to a bookstore and a 15-minute drive to an enchanting stone chapel that is one of my favorite places in the area.

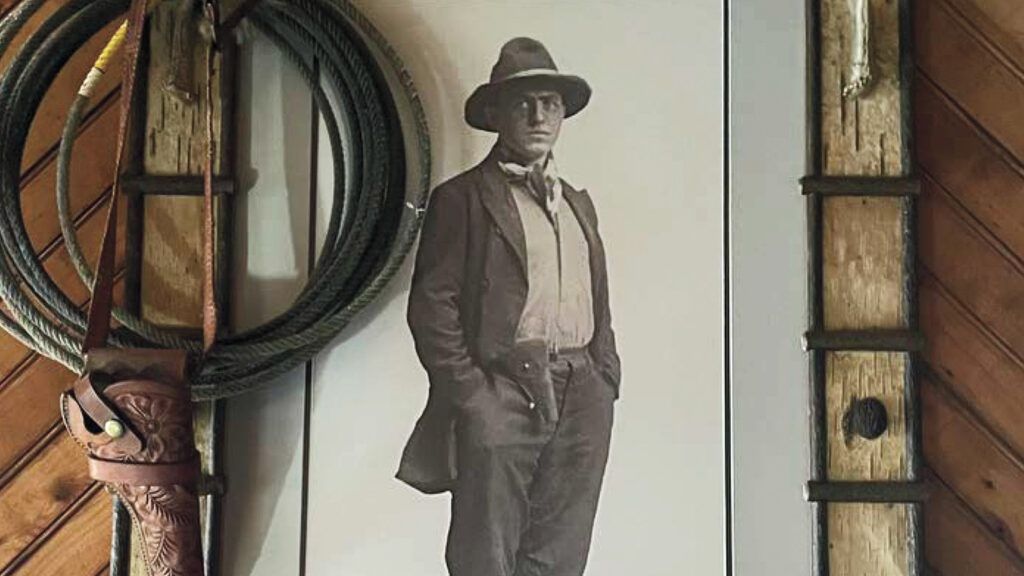

Browsing at the bookstore one day, I spotted a slim, green paperback called The Earl Covey Story: A Master Builder in the Adirondacks. According to the back cover, Earl Covey was an early-twentieth-century renaissance man of the mountains, renowned as a wilderness guide, an innkeeper, a stonemason, a trapper and an inventor. He also built several remarkable, one-of-a-kind structures using trees and rocks from the surrounding woods.

Why hadn’t I heard of him, I wondered? I’d read a lot of local history.

I was flipping through the pages when my eyes fell on a portrait of a young woman with long, thick hair.

I gasped. I’d seen that picture before. In my grandmother’s photo album!

I bought the book, hurried home and read it.

Earl Covey and I, it turned out, were related. The girl in the photograph was Emma Chase, Earl’s mother and my grandmother’s first cousin. Here was a long-lost family connection to the mountains I loved.

Ties between Earl’s branch of the family and mine started early, I learned. Emma, Earl’s mother, grew up on a lake owned by my grandmother. In the 1800s, my Chase family ancestors purchased 3,006 acres of cheap Adirondack wilderness, including two namesake lakes—Upper and Lower Chase.

Grandma inherited the upper lake. Memories flooded back of tales she told about life on those lakes, with their pine-shrouded shores, tangles of blueberry bushes and warm sand beaches. In August 1915, four visitors caught 444 bullhead there, in one day! And that’s no fish tale.

For Emma, the happy days didn’t last. She was only 14 when she married Adirondack pioneer Henry Covey. They had two sons, Clarence and Earl, and lived in various towns before moving to Big Moose, an even wilder, uninhabited Adirondack lake. Emma contracted tuberculosis and died when Earl was 13 years old.

For Earl, it was the beginning of a life shadowed by tragedy.

Two years after their mother died, Earl and his brother were out on Big Moose Lake in a canoe fashioned from a pine log. The canoe flipped, and Clarence drowned.

Soon after, Earl quit school to help run a hotel built by his father. He married at age 19 and fathered five children in quick succession.

Itching for a place of his own, he purchased a tract of land on an undeveloped neighboring lake. It was the middle of winter, but Earl set to work building what became Twitchell Lake Inn. He and a friend backpacked to the site and camped in a snow cave while starting construction.

The inn was a success, but two decades later, tragedy struck again. Earl’s wife died of pneumonia. Then one of his sons succumbed to the 1918 flu pandemic. Earl built a lovely stone bridge over the outlet to Twitchell Lake as a memorial to his son. A few weeks later, a second son died after an injury.

Earl seemed broken. He began talking of leaving the Adirondacks and moving to California.

That summer, a woman named Frances came to work at the inn. She was 13 years younger than Earl and a college graduate who had grown up in Boston. She knew nothing of the woods, but she fell in love with her stoic boss and they married.

Earl was regarded by his contemporaries as a real-life Paul Bunyan. He felled trees by himself and once hauled an entire cast iron stove on his back into a hunting camp. He could build a log cabin in days. He ran his hotel, guided hunting parties and organized weekly square dances.

Somehow, in the midst of all that, Earl also built numerous beautiful buildings that still stand today.

One of his best-loved buildings is Covewood, a summer resort on Big Moose Lake now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The first time I went there, I knew nothing of its history but I was wonderstruck. With its woodsy exterior of bark-covered spruce slabs, enclosed balconies, a wide veranda and a stone staircase, the inn appears at one with the landscape. It reminds me of a giant fairy house.

Also on the national register is Big Moose Community Chapel, Earl’s masterpiece. Turning to that part of the book, I realized with a start that the chapel is the very same chapel that I had been visiting and loving for years without ever knowing I was related to the architect. The story of the chapel distills everything else in Earl’s life of resilient faith.

The chapel is actually the second place of worship Earl built on that site. The night before it was to be dedicated, someone called Earl at home: “The chapel is on fire!”

Volunteer fire companies rushed to the scene but the pump they brought wasn’t strong enough to bring water from the nearby lake. Earl stood helplessly as his meticulously fitted spruce log beams and rafters, his hand-rubbed birch paneling, even his hand-laid fireplace succumbed to flames.

Having endured so much sorrow and so many setbacks in his life, no one would have blamed Earl for shaking his fist at God and walking away. Instead, he allowed himself only a few hours of teary-eyed silence before proclaiming, “We will rebuild!” Earl was accustomed to working in solitude. All his life, he had carried burdens both physical and spiritual. This time, God sent help to bear the load.

The day after the fire, a group of local residents, property owners and hotel guests gathered in a nearby boathouse. The smell of smoke hung in the air. A visiting minister conducted a brief service. It was 1930, the Great Depression bearing down, but the impromptu congregation of several different faiths vowed to raise enough money to rebuild the chapel.

The resulting house of worship was a triumph of beauty and reverence. Built of local stone and wood, it has a small tower and a vaulted wood sanctuary with arched windows looking out on the trees and the lake. When all seemed lost, God sent a community of angels to help Earl complete his architectural masterpiece.

As soon as I’d put all the pieces together, one weekday afternoon, Neil and I drove to Big Moose Lake. I had to get back to that chapel. Finding the door unlocked, we stepped into the empty sanctuary and sat down in one of the varnished wood pews.

I gazed out the windows at the surrounding forest. I pictured Earl setting each stone of the exterior in place, hoisting ceiling beams and arranging the pews just so. I thought of his many setbacks in life, all the times he could have given up and turned his back on a God who had not intervened in tragedy.

Earl never gave up. He looked for God in the midst of tragedy. He found God in his beloved mountains—our beloved mountains—and labored to help others encounter that same divine presence in the wild. I had experienced that presence myself long before I happened upon the slim, green paperback. But knowing Earl’s story added a richness I could never have imagined.

For more angelic stories, subscribe to Angels on Earth magazine.