I was on duty in the ICU when the hospital nursing supervisor pulled me aside.

“There’s a Jon Dennis in the ER,” she said. “Isn’t that your son’s name?”

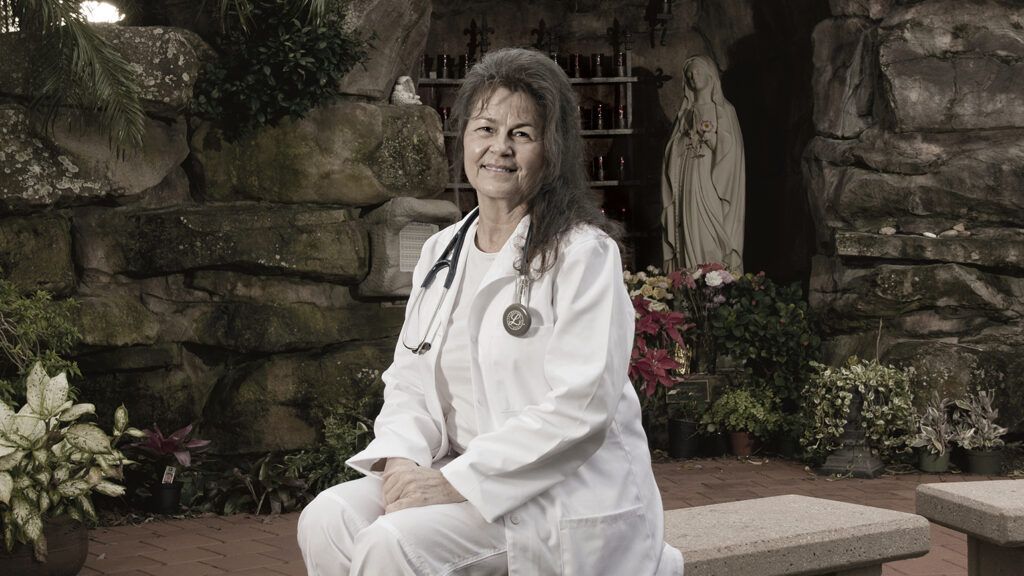

I’m an intensive care nurse at Jupiter Medical Center in northern Palm Beach County, Florida. For three years, my 27-year-old son, Jon, had battled addiction to pain pills. The supervisor knew about his struggle.

We raced to the ER. It was Jon. He was in a room by himself. One look and I knew what had happened. Overdose victims were all too common.

“Hi, Mom,” he said. His eyes and extremities were moving fitfully. Paramedics had brought him in after administering naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdoses.

“Oh, Jon,” I said. Then the nurse in me immediately asked for him to be hooked to a heart monitor, for an IV with fluids to be started and for blood work to be done. I wanted the top specialists in the hospital to see him. I could not bear to lose him.

Because I had already lost a son to opioids. In this same hospital. Six months earlier, Jon’s younger brother, David, had been admitted to the ER, to this same room.

David had taken opioids and drowned while spearfishing with Jon. He was put on a ventilator. A nephrologist ordered dialysis to flush the drugs from his system, but it was too late. My daughter, Jennifer, and I watched him take his last breath later that night in the ICU where I work.

Two sons. Two addicts. I’d dedicated my career to saving lives. But I couldn’t save my own children. What happened? What went wrong?

I’d wanted to be a nurse since college. I’d finished all my prerequisites for the nursing program when I fell in love and got married. I had a girl and two boys. I was happy being a wife and mother, but my marriage didn’t last.

Divorced, needing a job that could support the children and me, I went back to school and earned a nursing degree. David, my youngest, was 12 when I started working as a nurse. Juggling a demanding job and parenting was a challenge. But the kids weathered it. All three were A students in high school. Jennifer became a nurse. Jon worked in his dad’s plumbing business. David graduated with honors from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. He wanted to become a commercial pilot and supported himself crewing on yachts.

Nursing came naturally to me. I felt deep satisfaction every time I eased a patient’s suffering or helped doctors save a life. I was proud when I landed in the ICU at Jupiter Medical Center. Almost every day, I administered pain medication to my patients. Doctors prescribed opioids either by IV or pill, and it was assumed they were safe and non-addictive when used responsibly. I was happy to relieve my patients’ suffering by administering these meds, and the patients improved and felt better.

When he was 24, Jon hurt his knee riding a dirt bike and needed ACL surgery. The doctor prescribed an opioid medication. “I frequently give them to my patients,” I told Jon. “It’s going to make your recovery a lot easier.” I never imagined he would abuse them.

I said the same thing to David years later, after he hurt his back doing yard work and got a pain pill prescription. That spring, David was hired to help crew a yacht on a trip to Mexico. He assured me he’d be home in time for his college graduation ceremony.

He wasn’t.

Worried, I contacted the yacht captain. “I’m glad you called,” he said. “I don’t know where your son is. But he has a drug problem. You need to get him into treatment.”

My former husband and I booked the next flight to Mexico. We searched for three days before finding David in jail. He’d been mugged and drugged.

I was just grateful he was alive. We brought him home and took him to the hospital. “These pills, I’m addicted to them,” he said. “I want to get my life straightened out. Go to church and finish my flight certifications.”

“How did this happen?” I asked. I couldn’t understand it.

“I get pills from Jon,” he said. “He’s more addicted than I am.”

We were seeing more and more overdose patients coming into the hospital, but I’d had no idea my sons’ lives had spun out of control.

I tried to enroll David in a three-year treatment program, but the program rejected him. They didn’t think he’d be able to commit to the full length of it.

“Mom, don’t worry,” he said. “With God’s help, I’ll get through this.” He wanted to help Jon kick his addiction, but Jon pulled him more into his world. I was in a battle for my sons’ lives.

David said he was focused on his classes, but I noticed he was drowsy, not himself. He claimed he was exhausted from studying and working.

I begged him to get help. “People are coming into the hospital dead from these things. Please, David, do this for yourself, your family and me.”

David looked desperate. And worn out. “Okay, Mom, I’ll go for treatment,” he said. “And I’m going to try to get Jon to go with me.” That had been the reason David had gone fishing with Jon. To talk him into getting treatment. Hours later, David was dead.

His brother’s death spurred Jon to get treatment. Within days, he checked into a rehab facility for three weeks. But when he came home, he began using again.

“I’ve got it under control,” he assured me. “I can get straight on my own.”

By now I knew better. But what could I do? Jon was an adult. I couldn’t force him into treatment. I fasted and prayed night and day.

I was full of questions. Of all those patients I’d given pain medicine to, how many had become addicted? People from all walks of life were coming into the hospital addicted to opioids. Was there something wrong with the medicines themselves? Their availability? Or just the way they were used?

Then Jon overdosed. Even that experience didn’t convince him to take recovery seriously. Only after an 11-month stint in rehab three years later did he get clean. He’s been drug-free ever since.

For a long time, I was distraught over what happened to my sons. I grieved for them. Life wasn’t the same without David. Gradually, through prayer and my own research, I learned how to use my family’s experience to help patients.

Opioid pain medication, I discovered, is nearly identical chemically to heroin. Both drugs, at a high enough dose, produce a euphoric high and are extremely addictive, with severe withdrawal symptoms. Even when taken at the prescribed dose for a limited time, opioid pain medication can still be addictive. Patients can become physically dependent, beginning a cycle of higher and higher doses, increasing addiction.

There are other ways to manage pain. Opioid addiction is worse in America than anywhere else in the world. In Japan and Europe, opioid pain medicines are prescribed at vastly lower rates, generally only for people undergoing major surgery or at the end of life. Most other pain—bad backs, sprained ankles, pulled teeth—is treated with rest, physical therapy and over-the-counter painkillers. I’ve found that prayer, exercise, eating well and sometimes just relaxing with a cup of tea help me deal with the pains and stresses that life inevitably presents.

Tentatively at first, then with more confidence, when I sensed a patient was open to talking, I began sharing my thoughts about pain management with patients and families. Nurses don’t prescribe medicine or direct patient care. That’s the doctor’s job. But nurses do educate patients about how to use their medicines. And it is a nurse’s calling to ensure that patients are well cared for and safe. To do no harm.

I took a close look at the medicines I was administering to patients and sending home with them. Often I was shocked by how many painkillers they were taking. When it felt appropriate, I shared my own family’s story, cautioning patients about the addictive properties of opioids and offering other, non-addictive ways to manage pain. Sometimes I even talked to doctors and persuaded them to reduce the amount of pain medication prescribed.

“I lost one child and almost lost another,” I tell patients when I feel my story might help them make an educated decision about medication. I hold Jon and David close to my heart every time I have one of those conversations.

This year, after three years of study, I expect to become a licensed nurse practitioner, which will enable me to diagnose patients’ conditions and prescribe medication. My dream is to move to northern Michigan, where I was raised, and work in a small-town emergency room.

As a nurse practitioner, I’ll do all I can to help my patients. One thing I never plan to do is prescribe opioids. I prefer alternative methods for relief. If patients want pain medicine, they’ll need to visit other practitioners.

I’d rather not go there. Not after I watched David take his last breath. Not after seeing the glazed look in Jon’s eyes as he lay in the hospital, just pulled back from a fatal overdose. Not after I’ve learned that it isn’t always the user’s actions or character that causes addiction but the drug itself and its availability. That is the enemy we must defeat, with almighty God’s loving hand at the ready.

Editor’s Note: For more stories about addiction and recovery, check out our new series “Overcoming Addiction” in Guideposts magazine. The February issue featured the story of a West Virginia fire chief whose faith inspires her to never give up on her city’s addicted citizens.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.