At Bridgeport High School in Ohio I was quarterback, the leading offensive player, on the football team. In baseball I was the leading hitter. In basketball, the leading scorer. To say that I didn’t glory in the spotlight, appreciate the acclaim and savor the headlines would be false. We all like to take bows.

But when I went to Ohio State on a basketball scholarship, I discovered that everyone on the squad had been a standout in his part of the country. I clearly remember one day early in the season, when I was still feeling my way around, the coach gathered us around him during a break.

“Which player makes the most points, grabs the most rebounds or shoots the best percentage, matters little compared to which team scores the most points,” he told us. “Poor teams often have one or two players who stand out; good teams have five who work together. It is amazing what can be accomplished when no one cares who gets the credit.”

Suddenly, sitting there in that circle of perspiring athletes, I came to a startling realization. To win a starting job on the team, I had figured I would have to impress with my shooting ability, but the team was already loaded with shooters. What it needed was someone to concentrate on defense. I decided then and there to take that role, and the decision was to make all the difference from then on.

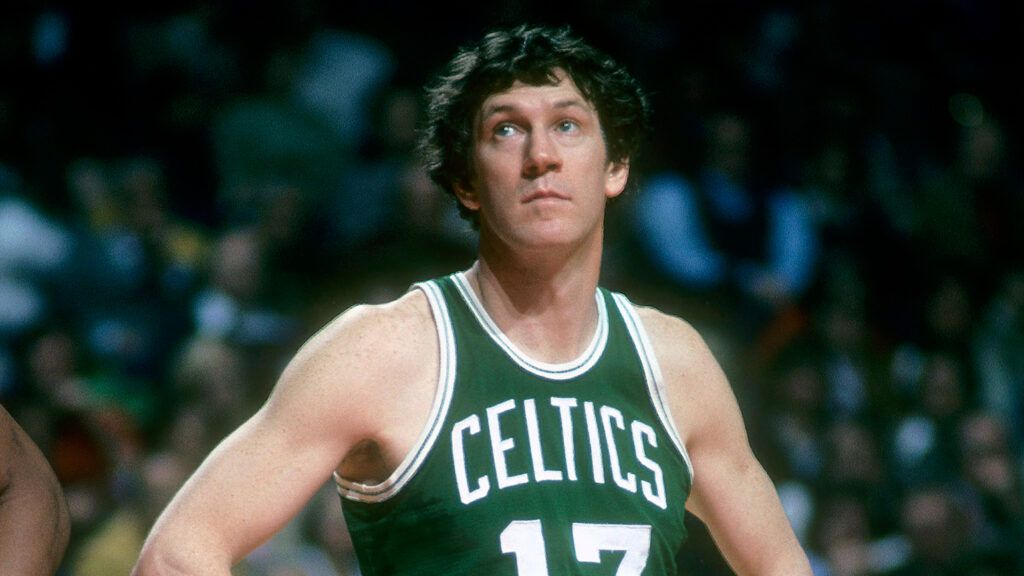

Last basketball season, 16 years later, I saw the same principle work to perfection once again in the seventh and deciding game of the National Basketball Association playoffs between the Milwaukee Bucks and my team, the Boston Celtics.

Before the game, coach Tom Heinsohn called us together in the locker room. There was some nervous conversation, the shuffle of sneakers, the squeak of a wooden bench, then quiet except for the sound of Tom’s chalk on the blackboard. He was diagraming a new strategy he wanted us to use against the Bucks. Although I had led the scoring for Boston in the first six games, which we had split 3-3, our coaches had noticed that Milwaukee was concentrating more and more on me.

“What I want you to do is play decoy, John,” the coach said. Instead of playing a strong scoring role, I was being asked to draw the defense to me, away from the basket, freeing someone else to score. It sounded like a good idea—and it was. By half time we had built a 13-point lead—the score was 53-40. My teammates Jo Jo White, Don Chaney, Paul Silas and Dave Cowens were more than carrying our scoring load.

But Milwaukee made some adjustments, and in the second half they came back with a rush. Soon our lead was down to five points and I began to wonder if it was time for me to begin shooting.

But we stuck to our pregame plan. I contributed a few points, but mainly I continued to play the decoy role. Then, near the end of the game, in a desperate attempt to close the gap, Milwaukee turned its attention away from me and gave me a wide-open opportunity. Driving up the middle of the court, I scored a basket and got a foul shot to boot. It was a key three-point play because it put the game safely out of Milwaukee’s reach and minutes later the championship was ours.

I hear a great deal today about people doing their own thing and I believe in that. Individuality is great. But sometimes we all need to subordinate ourselves for the good of the group.

Teamwork was taken for granted by the townspeople of the small eastern Ohio village of Lansing where I grew up. Just across the river from Wheeling, West Virginia, Lansing is in steel and coal-mining country, where people work hard to make a living. But hard work has its rewards and this rugged existence seemed to bind the people together. They cared about one another and were always ready to help. Teamwork was part of survival. No one asked for any credit for what he or she did; they just did it.

If the mines and mills closed and men were out of work, people like my mother and dad did their part.

Together they ran Havlicek’s General Store for many years, dispensing everything from groceries to animal feed, ladders, boots and fertilizer. When customers lost their jobs or couldn’t work, my folks extended credit to them, sometimes way beyond the point of business prudence. And if those families got too far behind, where it might be impossible for them to catch up, dad and mom would devise ways to help them out of the hole.

They would allow the customer to do odd jobs—such as filling stock, sweeping floors, loading trucks and delivering groceries—to relieve the pains of a growing grocery bill.

For the most part, I suppose we were looked upon as people of some means in our community; but the money must have all been on the store’s books, because my brother, sister and I weren’t ever spoiled with luxuries. We had plenty to eat, but no frills. Though no one drew us any pictures, everyone seemed to know that life was a game which required plenty of cooperation and teamwork.

Someone once suggested that I must have been born with a basketball in my hand, but I didn’t own a basketball until I was 14 and I never had my own bike. Being bikeless, however, may have had its rewards. I ran everywhere, which built up my legs. That helped in sports, which I was involved in year-round.

So much has happened to me since those days. Basketball at Ohio State is among the highlights. When I was a sophomore we won the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship, and we went to the finals the following two years as well. When it came time for the pros to make their picks, coach Red Auerbach of the Boston Celtics drafted me in the first round because he thought I could play a supportive role for his already talent–laden team.

When I became a starter, I was called upon to le ad more and to score more, which I have been able to do. Many people who had watched me in college were surprised to see me average over 20 points per game as a pro. They were so accustomed to seeing me play defense that they couldn’t believe I could also put the ball in the basket.

Lately, knowing that retirement is not more than a couple of years away, people have been asking me about my future. During the off season I have been working as a manufacturer’s representative in Worthington, Ohio, and I expect to join the firm full time after retiring from basketball. I may also assist my friend, Ohio State basketball coach Fred Taylor.

My confidence for this transition is bolstered by a habit I began as a teen–ager. Each day I read a devotional with a Bible verse and prayer. From that practice, from my association with many fine people, from the influence of my wonderful parents and the support of a great wife, I have developed a faith and an attitude about life. It is simply that each of us has a role to play and whatever it is, we should do it with our whole body, mind and soul. That isn’t always easy, but I know from experience that the greatest rewards go to the people who give their all and don’t worry about who gets the credit.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.