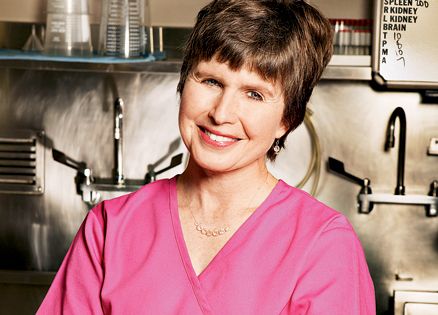

I’m a forensic pathologist. My job is understanding the cause of death, but it’s also to speak for the dead. Since 1993, as coroner for Anoka County, Minnesota, I’ve been doing everything in my power to answer one question: How did this person die? Then I explain it to family members, physicians, law enforcement and the courts. Often, death is a riddle.

I’m also a doctor, and like all doctors, a healer. How could a person who spends her time examining the deceased call herself a healer? Well, I’ll tell you.

I come from a medical family. My dad is an internist and, growing up, I tagged along with him on house calls, watching him solve the mysteries of his patients’ illnesses. He practiced medicine like the country doctor you see in old movies: worn leather medical bag, stethoscope draped around his neck and a big, reassuring smile that said, “Talk to me. I’ll listen.” Same with Mom, a nurse. Watching the difference the two of them made in people’s lives, it was only natural that I’d go into medicine myself. In no other job did a love for knowledge and a love for people meet so perfectly.

It was Dad who suggested forensic pathology. He recognized my excitement over finding answers—my insatiable curiosity about how the human body works. “You’d be a doctor’s doctor,” he told me. “It’s the basis of all medicine. Nothing teaches you more about life than death.”

I liked the idea of discovering the cause of death. There is no more intimate possession than the body itself. Performing an autopsy, I don’t see an anonymous corpse in front of me, but the evidence left behind of that person’s soul: an open book telling me about how he or she lived. If well and decently, that’s evident in a thousand different ways. If badly, that’s evident too. A life story is visible right there in the organs. You can tell the choices people made in life.

I am passionate about my work. My autopsy reports are the last word on my patients. Each case is a new challenge, a new mystery, and I can’t rest easy until I’ve made sense of it. I’m not at peace with a case until I’ve discovered exactly how the person I’m examining has passed on.

Eventually an idea formed in my mind. What about the families? If knowledge really heals, why not share the knowledge I gained in my autopsies? Why not personally tell them the cause of death? Nothing in life hurts as much as losing a loved one. Maybe talking to me could help ease the family’s grief, perhaps even help in the healing process. I called the next of kin whenever possible and shared my knowledge of how their loved one had died. In almost every case it helped them.

It helped me too, fulfilling my desire to be a healer, like Mom and Dad. I opened myself up to the survivors’ pain, grief and anger, as well as their hope and gratitude. And something more…more than I could ever have imagined.

Take Julie Carson, the wife of a man named Randy on whom I performed an autopsy. She’d come home one day to find Randy dead on the floor next to his easy chair, the TV remote still in his hand.

In the left ventricle of Randy’s heart I discovered a large tumor that penetrated the main chamber. I suspected the tumor had played a part in Randy’s death, and called in a specialist to help interpret the evidence. The tests took weeks, which delayed the death certificate. Julie was left waiting, alone with her grief. In 17 years she and her husband hadn’t spent a single night apart. How could God have taken him away from her? And so suddenly, without even a chance to say one last “I love you.”

I called Julie the minute the report was ready. She wanted to know everything. “The growth in your husband’s heart was benign,” I explained. “But a piece of it broke off and entered one of his coronary arteries. The tumor fragment plugged the vessel, just as a blood clot would have. In essence, Randy died of a heart attack.”

Julie was silent for a moment. “Did he suffer?” she asked. I told her that in my opinion, Randy had slipped away painlessly.

“With his favorite toy in hand,” she said, her voice softening. “I usually got into bed while Randy was still watching TV, channel-surfing mostly. But I never shut my eyes till I heard him coming up the stairs. Can I tell you something, Dr. Amatuzio?”

I thought of my dad, who always had time to listen. “Of course,” I said.

“After Randy died, I couldn’t sleep. Then something happened. One night I finally drifted off. Footsteps in the hall woke me. I just knew it was Randy. Sure enough, he walked right into our bedroom, sat down next to me and took my hand. We talked about the kids, our finances, the house. ‘Our love is forever, he said. ‘Just think of me and I’ll be there.’ I know our love still connects us, Doctor.”

You might think this story is a rarity. But the fact is, over the years I’ve heard scores of stories like it. They’ve opened me to a whole world: the one that lies beyond the borders of death. Having grown up in the church, I understood the concept of an afterlife. Yet how amazing it was to confront it as a doctor!

Mary Bare was the mother of a young man named Greg, who’d died in an auto accident. I called Mary after conducting his autopsy and asked if she had any questions. Her first one was the same as Julie’s: “Did he suffer?” In this case as well, I was able to tell Mary that in all likelihood, Greg hadn’t suffered.

Mary seemed almost to expect that answer. “Dr. Amatuzio,” she said, “can I tell you something?” When Greg was a boy he had a favorite babysitter named Sheila. She was Mary’s favorite too because she had a special knack for comforting him. Shortly after Greg’s death, Mary called Sheila.

“Sheila told me,” Mary said, “that on the night Greg died, she had been awakened by a loud voice saying ‘Hey, Sheila!'”

Sheila sat up and saw Greg—all grown up—standing next to her bed. He was very distraught that his death had caused such pain and sadness. Sheila didn’t stop to question whether she was dreaming. She did what came naturally and comforted him, just as she had done so many times when he was a boy.

A few nights later Sheila was awakened again—this time by a gentle light filling her bedroom. Again, Greg stood at the foot of her bed. But this time there was no more confusion, no more sadness about him. “Tell Mom I’m okay now,” Greg said. It seemed that Greg’s life was going on, in a new world where he was at peace. Sheila was relieved to get Mary’s call. It was confirmation that she should relay this message of comfort sent from God to a grieving mother.

Yet sometimes people do come back from the dead. I was having lunch one day with several law enforcement officials, including a local sheriff—a shrewd and highly respected man. People had heard about my interest in the subject, and somehow the conversation took that turn. The sheriff spoke up. “Dying’s not the big deal people make it out to be. I drowned once.” I looked at him. He didn’t say “almost drowned,” he said “drowned.”

The sheriff had grown up on a lake. “My brothers and I spent just about every day of the summer swimming there and carrying on. We used to dive off the lifeguard tower and race to touch the bottom.”

But that got too easy. The sheriff and his brothers added a new twist to the game. The tower’s legs were ladders, the rungs of which started out wide and got narrower toward the top. He and his brothers would weave back and forth between the rungs as they made their way up. One day, just a few feet from the surface, the sheriff got stuck. “I looked up and saw that my brother had made it to the surface,” he said. “I panicked. Then I blacked out.” The sheriff came to in a rescue boat after mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

“Do you remember anything from when you were unconscious?” I ventured.

The sheriff looked down. Something in his face changed. “Why, yes,” he said. “I do. I don’t usually talk about it, but it’s as clear as if it were yesterday. I remember thinking, I’m going to die. I took in a large gulp of water, and all of a sudden, I was up above my body, looking down on it. There were beautiful colors everywhere. I felt sorry for my body, but I wasn’t worried about it. There was all sorts of activity. My brothers and the lifeguard were there. But I felt perfectly calm, and found myself speeding along above the surface of the water, toward someplace so near yet so perfect I never could have imagined it. Then, all of a sudden, I was jolted back into my body.”

The sheriff said that what he remembered most was that when he came back from the stunningly vivid world he’d entered for a moment, everything in the regular world looked dull—as if he’d gone from a color movie to one in black and white.

“You know, Doc,” the sheriff said, looking at me with a twinkle in his eye, “I know that you’re the coroner and see this stuff every day. You know that it bothers a lot of folks. But I’m not afraid of death. Not after what happened to me.”

Can I explain all of these stories I’ve heard, in the way that I can explain exactly why a body I examine died in the way it did? Probably not. We are not meant to see the soul. Yet I have come to believe that these experiences reveal the truth of what I believe: Dying is part of a larger picture, a moment of transformation on a path of eternal life. Discovering the cause of death opens the door to a grander reality. We don’t end when our bodies give out. In a life full of solving mysteries, that’s the greatest one I’ve discovered—the mystery of the soul.