I sat by the front window cutting out paper dolls and watching the snow pile up across the mountaintop. The flakes had started falling the day before and hadn’t let up—an unusually early storm for November in West Virginia.

If anything it was coming down harder now. “Look at the drifts!” I exclaimed. “They’ve nearly covered the fence.”

Mother came in from the kitchen.

“Looks like it’s just going to be us this year,” she said. I couldn’t help but notice the disappointment in her voice for our Thanksgiving 1928. “No one could get here on a day like this.”

I was disappointed too. We lived in the high country, nearly two miles off the main road. Without a telephone, we were pretty isolated, especially come winter.

Thanksgiving weather usually made the dirt roads hard with frost, so we could hope for a houseful of guests. After that, we were on our own. I wanted to see my cousins and aunts and uncles as much as Mother did.

“We’ll have a nice meal to be thankful for,” she said, trying to sound cheerful.

Mother always made special dishes: candied sweet potatoes, spiced peaches, cranberries and crisp celery arranged in a beautiful cut glass dish. My mouth watered just thinking of them. But wouldn’t it taste better if we had guests? I thought.

Mother went back to the kitchen. Father tended to the fire. I went outside to join my brothers and sisters in a snowball fight.

It wasn’t long before we were freezing cold, our clothes soaking wet. The snow was over my boots and melting down into them. Mother beckoned us to come in.

We came in through the back hall, where we hung our coats and hats. Our dog, Major, barking outside, brought us all to the windows that faced the front of the house.

“Look!” Mother said. Down by the lower gate, more than 100 yards from the house, was a man coming quickly through the snow. Dad let Major in the front door, still barking in excitement.

From time to time transients came by in search of a warm meal or a place to spend the night. Mother never turned anyone away.

“We might be entertaining angels unaware,” she always said.

But that was in the spring and summer, maybe fall. Never in a blizzard! This man didn’t even seem bothered by the snow. His long strides never faltered as he walked right to our front door.

“Come in,” Dad said. “I’m Seymour Johnson. I don’t believe I know you.”

“Goodman’s the name,” the man replied in a cheerful voice. I peered around the corner into the hall for a closer look as Dad helped the man take off his overcoat and hat and ushered him into the sitting room.

He was tall like Dad and wore a nice suit. Strange clothes for a traveler, I thought. Didn’t he know it was snowing?

Mother went to welcome him.

“He comes from Sandy Low Gap and has to be in Widen tomorrow morning,” she reported to us kids in the kitchen, “but the train isn’t running today. He set out on foot!”

That town was almost 20 miles north of us. How could he have passed through Sandy Low Gap? The drifts would have been over his head.

“His trousers aren’t a bit wet,” Mother said. “But never mind that, we have work to do.”

She didn’t have to try to sound cheerful now. We had company for Thanksgiving, even if it was only one stranger.

The kitchen became a flurry of activity. Mother asked me to set the table.

“Go to the cellar and get a basket of apples,” she said. “We need a proper centerpiece for our guest.”

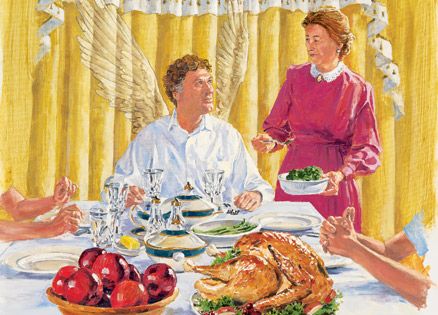

We called dinner and Father brought Mr. Goodman into the dining room, his hand on his shoulder as if they were old friends. We took our seats, and Mother asked our visitor to say grace.

I looked at her wide-eyed. She’d never before asked a stranger to pray. But Mr. Goodman didn’t even blink before bowing his head.

“Dear God,” he prayed, “I thank you for the blessings of this day…”

His voice was warm and soothing. Mother’s “amen” echoed his. We passed the food and waited for him to take the first bite.

“Delicious,” he said. I had to agree. Thanksgiving dinner had never tasted so good.

“Your father tells me you like horses,” Mr. Goodman said to my brother. One by one he engaged all of us in conversation. He listened raptly to stories about horses and schoolwork. He even asked the names of all my dolls.

He praised Mother’s cooking until she blushed. The apples sparked a lively exchange with Father about horticulture. Mr. Goodman was only one man, but somehow with him at the table the house seemed full of guests.

“It’s funny,” my sister remarked as the dishes were cleared away. “He found a way to turn aside every question we asked about him.”

We moved to the sitting room, where Mr. Goodman spied the violin on the bookcase. “Do you play?” he asked Father.

“I saw a bit,” Father replied. Soon we were tapping our toes to “Soldier’s Joy.” Father started clogging. Then Mr. Goodman joined him, to our delight.

We ended the evening with popcorn and chestnuts roasted over the fire. I hated to go to bed.

Mother showed our new good friend to his room and we all said good-night. I could not remember having a better Thanksgiving.

I awoke to the smell of bacon frying. But Mr. Goodman wasn’t at the table.

“He left sometime during the night,” Mother said. “I found this note on the dresser.”

She read it to all of us kids: I’ll always remember your wonderful family and the hospitality you showed me—the delicious food and after-dinner festivities. May you have many more happy Thanksgiving days. A. Goodman.

Just then Father came in the front door, stamping the snow from his feet.

“There are no footprints out there anywhere,” Father said.

“Oh, my. Do you think—?” Mother paused.

Father nodded and his voice had a note of joy. “Yes, our visitor was an angel. I’m sure of it.”

I’ve celebrated a lifetime of Thanksgivings since that one, most surrounded by friends and family. But none has ever been more special than the one I spent with A. Goodman. And each year as I reflect on my blessings, I pause to thank God again for answered prayers and the opportunity to entertain unaware.