There was once a boy who loved the things 10-year-old boys in the 1940s loved: ice cream, Jack Armstrong on the radio, Sunday school, cowboys and Indians—especially Indians. But this boy had a terrible secret. He lived in dread of his father, a dread that made him feel he was never safe.

That boy growing up in Columbus, Ohio, was me. I tried to love my father because I did not know other boys weren’t beaten when they spilled a glass or broke a toy. But mostly I feared him. I feared his very shadow.

He was a stocky, muscular man whose roaring voice gave an extra dimension of profanity to the curses he spewed when he had been drinking, which was often. He liked to use a leather strap, cracking it like a lion tamer. A lion tamer rarely lets his whip touch the animals. On me, Dad’s strap always left a reminder of his untamable fury. I wondered why my father was so full of anger and if it was my fault.

When my mother tried to stop him, she learned soon enough that any intervention on her part only provoked greater punishment for us both. We simply tried not to upset him, especially when he was drunk.

One pleasure my mother and I enjoyed together, though, was church. I especially loved Sunday school, where I discovered a father who was not frightening but all-loving and all-forgiving, who had creatures at his command called angels. We were taught he would send them to us in times of need. I thought a lot about angels and what they looked like, and I prayed I would not be frightened if I ever did see one. I spent so much of my boyhood in fear.

I loved to sing in church. At school I could hardly wait until music period so I could throw myself into “God Bless America” and “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” I had a strong voice too. If someone had asked me my greatest ambition, I would have answered without missing a beat: “Traveling the world, singing with an orchestra like Lawrence Welk’s!” When I sang, I felt free from fear.

Though my father held a steady job in sales, we were not well-off due to his carousing, and he often used debts and the hard hours at work as excuses for his drinking. One September day it all came together in an explosion of rage.

That morning my father reminded me to do my chores—not that I ever needed reminding. There was the devil to pay if I forgot. After school I cleaned the house and settled into the den to listen to The Lone Ranger on the radio. Transported by the sounds of galloping hooves and ricocheting gunshots, I barely noticed my father come home until I heard him bellow, “Bob, did you do your work?”

“Yes, Pa,” I answered.

I hoped he would go upstairs and sleep, but instead I heard his lurching footsteps heading for the living room, followed by muttered curses and something crashing to the floor. My whole body began to quake.

“Get in here, boy!” he roared.

I snapped off the radio, my mouth as dry as dust, and went to my father. His face was flushed and his eyes smoldered ominously.

“You telling me you cleaned this room?”

“Yes, Pa….”

“Liar!” He kicked the scattered pieces of a broken lamp across the floor. “What about that mess?” He began to loosen his necktie, a bad sign.

I knew better than to argue. He grabbed me by the collar and dragged me toward the basement door. In one swift movement he reached behind it, snatched his old, heavy leather belt and pulled me down the stairs, my heels clattering on the steps. I was so scared I could hardly breathe.

He yanked on the light chain. The suspended bulb swung crazily and shadows convulsed on the walls. A small length of clothesline hung from a pipe running along the ceiling; my father used it to tie my hands to the pipe so that my feet dangled above the floor. He jerked the back of my shirt up over my shoulders.

“Now,” he snarled, snapping the leather belt, “I’ll teach you!”

I closed my eyes and braced myself for three impressions: the crack of the belt as it struck through the air, its flaming sting on my flesh, and the smell of alcohol as my father expelled a grunting breath with each furious effort. Please, dear God, I prayed, please save me.

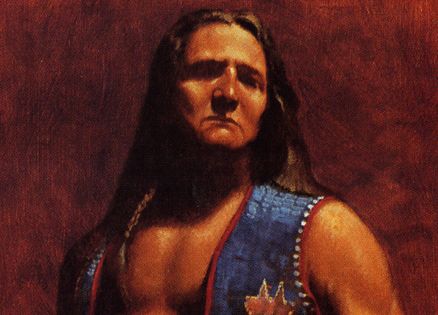

It was then he came, appearing silently and fully to me—a tall, broad-shouldered, unmistakable American Indian, hair the color of shiny coal hanging down his back over a blue-beaded vest. Everything about him spoke reassurance and peace. I knew God had sent him, and I wasn’t frightened. His deep, scintillating eyes searched mine for an instant, then turned piercingly on my father, who was at the point of whipping me. I heard a gasp and the belt fell to the floor, its brass buckle rattling on the cement. I turned to see my father cover his face with trembling hands and then stagger up the stairs.

When I turned back, the Indian was gone. But I knew for certain that in one form or another that noble angel would always be there for me.

I don’t know if my father saw the same angel I did or if he saw anything at all. When he came down a few minutes later to untie my hands, he was silent. He never spoke of the incident. And he never laid a hand on me again.

Something happened that night that seemed to open up my life to all the possibilities of God’s world. I felt I had been given a measure of confidence I had always lacked, except when I sang. The next morning at school my teacher surprised me with an announcement. “Bob,” she said after homeroom, “we’ve picked you to audition for the Columbus boys’ choir this afternoon. Only a few boys get selected. Do your best.”

I drew in my breath. The Columbus boys’ choir was a local group that had gained national fame. I never dared dream I was good enough to join.

After lunch I dashed home, put on a tie and hopped a streetcar to the school where auditions were being held. The headmaster, Mr. Hoffman, patted my shoulder and straightened my tie. “Show us what you’ve got, Bob,” he said.

In a bright soprano voice, I sang my heart out, a Mexican song about a youth who escapes home through a window to find his lady love. A few days later I got the news: I was chosen. I had never known such happiness. For the next five exhilarating years I lived and traveled the world with the choir. We had our own school and held class on a bus when we were on the road. It was during those five years that I began to grow into a man, one who would be different from my father.

Dad died years ago, and I pray that he made his peace with God. I don’t know if I could have ever fully loved my father, but I have forgiven him, and sometimes that is the only love we can give. I understand him better now, knowing he himself had been horribly abused as a child. What he did to me was what had been done to him.

But it was not what I would do to my two sons. That terrible cycle of violence was finally broken one night when I was 10 years old and one of God’s angels stepped between me and a leather strap, banishing my fear, giving me reassurance.