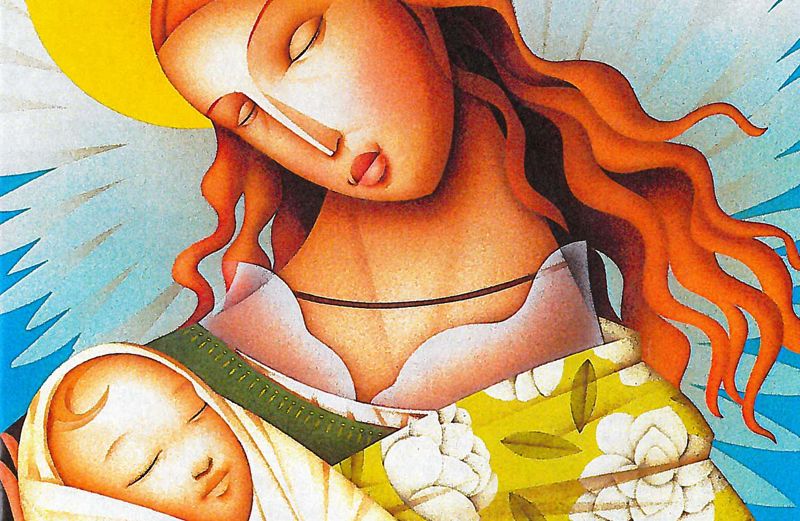

The scent of gardenias wafted through the window as a breeze billowed back the curtains. I rocked my 3-year-old daughter, Kenly, slowly in our La-Z-Boy.

Such a simple thing, holding your daughter in your arms, feeling the softness of her skin on your own, the warmth of her breath on your neck. For me it was the most precious part of being a mother–something I could never get enough of.

Maybe it’s because I didn’t get to hold her in those first moments right after I gave birth, the moments when a mother longs to keep her connection to the life that has been growing inside her for so long.

In my case, it wasn’t long enough. Kenly was born three months premature in an emergency C-section, just two pounds, seven ounces, and 14 and a half inches long.

I got only a glimpse of her little body before the nurse whisked her away to be cared for by others. My husband, Rocky, held my hand as the doctor turned his attention to us.

“We’re going to put your daughter in an isolette–it’s a protective bubble. Her immune system isn’t fully developed. She’ll also be on a respirator until her lungs grow to normal size. You’ll be able to touch her, but only through an opening in the isolette, until she’s out of the woods.”

Dazed and drained, I tried to absorb what he was saying. It wasn’t supposed to happen like this. I had read so many books about becoming a mother, sat in our great big La-Z-Boy recliner practicing the right way to hold my baby.

Now it was like I too couldn’t catch my breath, thinking of my daughter fighting to live in a world where even her mother’s touch could be dangerous.

Later that day we were taken to visit Kenly in the neonatal intensive care unit. It was an open floor with a nurse’s station in the center and dozens of babies in isolettes spaced a few feet apart. I was wheeled in on my hospital bed by one of the nurses so I could gaze at my sleeping daughter.

Her head was the size of my fist, her face almost covered by the respirator mask. IV’s were in her arms, which were no thicker than her daddy’s thumb. Her little chest was concave and her skin nearly translucent. If only she were still safe inside me where she could become strong.

Instead she lay in this plastic bubble where I could not even touch her cheek. “Mommy’s right here, Kenly,” I said. “I love you.”

I barely left her side. Even after I was released from the hospital I spent the entire day on a chair beside her isolette, trying to see if she had gotten bigger, telling her about all the people who were praying for her, or singing lullabies and hymns.

Sometimes the nurses would let me hold the syringe for her feeding tube or let me help weigh her, so I could touch her for a moment. As soon as I got home each night, I called the nurse on duty to check on her one last time before falling into a fitful sleep.

Finally after two and a half weeks, the nurse laid Kenly gently in my arms. I longed to hug her tight but could only hold her tiny frame gingerly in my hands, like a china doll. I turned my face away so my tears would not fall on her, and the nurse soon returned Kenly to her isolette.

The windshield wipers labored against sheets of rain as Rocky and I drove home that night. “I hate to leave her too,” he said, “but she’s in the best of care.”

“What about when she cries, not because she’s hungry or wet, but because she just wants to be held? After everything she’s been through, I wish I could give her at least that much.”

But soon I wasn’t even able to visit her as often as I wanted. I had to return to work at least part-time so I’d be able to take time off when Kenly came home.

I made a tape of myself reading nursery rhymes, singing, telling family stories–so she’d be able to hear my voice even when I wasn’t there. I stopped by to see her before work each day.

In my office, sometimes I’d close my eyes a moment and imagine Kenly in my arms, looking at me, reaching up to touch my cheek. Each night I returned to her side. “When we get home, Kenly, I promise all we’ll do is sit in the rocking chair and be together.”

I would carefully reach into the isolette, lay my hand on her chest and pray, God, please keep my baby in your arms while I’m away. Let her never feel lonely or frightened. Give her strength. Help her grow.

Two months after Kenly’s birth her doctor gave us the news we’d been hoping for. “I think her lungs are almost strong enough so she can go home,” he said. “But she’s going to need a lot of care. She’ll be on a food and medicine schedule every three hours, around the clock. Are you prepared for that?”

He didn’t have to ask. I would’ve done anything to get Kenly home. After 10 weeks of having to let strangers care for her, at last I could hold my daughter whenever I wanted. I kept her crib in our room and often she ended up in bed with us.

It felt so good to be able to comfort her when she cried or to sit in the rocker and sing to her like I had when she was in the hospital.

That’s just what I’d finished doing that spring afternoon last year. The air was thick with the scent of gardenias. I laid the book on the coffee table and cradled Kenly in my arms. “Are you cozy there, honey?” I asked her.

“Yes, Mommy.”

I rocked back and forth a few times, humming a made-up tune. Kenly nestled in closer to me. “You’re so soft, Mommy,” she said, “just like the angels.”

Angels? Had we read a book about angels lately? No.

“Which angels, honey?” I asked.

“You know, Mommy, the angels who held me when I was a baby,” she said.

I stopped rocking and sat her up on my lap so she faced me. “You saw angels when you were a baby, honey?”

“Yes,” she said. “They held me all the time. Sometimes they passed me around to each other. They were so pretty.”

“Angels held you,” I marveled. Then I hugged my daughter tight, turning my tear-streaked face away just as I had when I’d held her for the first time.

Hold her close in your arms, God, I had prayed. Now I felt his arms around us both, mother and child, who’d always been in the best of care.

Download your FREE ebook, Angel Sightings: 7 Inspirational Stories About Heavenly Angels and Everyday Angels on Earth.