The gray sky outside my kitchen window matched how I felt inside. Hopeless. I sighed and turned away. Life had lost all meaning.

Nearly a year earlier, on a sunny Fourth of July day, I drove to a nearby lake to celebrate with friends and family. It was my birthday. After a long workweek, I was looking forward to our picnic. And I couldn’t wait to get in the water. I loved to swim.

“Here I go,” I shouted, laughing, as I dove headfirst from a boat dock into the lake. That was the last thing I remember. I was pulled unconscious from the water with a severed spine, paralyzed from the waist down.

After months of hospitalization and rehabilitation, I was finally home. But things weren’t going well. I had to adjust to many lifestyle changes. I was impatient with myself as well as my three teenage daughters.

Turning from the kitchen window couldn’t keep the grayness at bay. Oh God, what am I going to do? My life has fallen apart.

A few days later, I poured out my despondency to Jerry, a good friend and neighbor who came to visit in my front yard. “I don’t feel like I have a reason to get out of bed,” I told him.

Jerry was quiet. His eyes were focused on my mulberry tree. “Look,” he whispered. “There’s a male cardinal. On that lower branch to the right.”

I saw the bird with its long tail, black mask and bright scarlet outfit, a dashing crest on his head.

“They like to nest in thick shrubs,” Jerry said, “and mostly eat seeds. They dine regularly at birdfeeders, especially in the winter.”

Cheer, cheer, cheer, the cardinal sang in a sweet voice. I’d seen cardinals before, in passing. Now as I studied this one, I realized I’d never really seen a cardinal. He was stunning.

Cheer, cheer, cheer, he trilled again before leaping into the sky.

The next day, Jerry pointed out a flock of cedar waxwings. “They’ve landed in your mulberry tree!” he said. His enthusiasm was catching. As I watched the elegant birds with their golden plumage, crimson wing tips and inky eye masks, something clicked. Curiosity, like a light, awakened inside me. And with every bird Jerry identified, the light grew brighter.

On his next visit, Jerry brought along his field guide. In it, he’d written the date and location next to every bird he’d seen since 1991. I was transfixed by the entries. I couldn’t believe how many different birds he’d observed right here in our neighborhood! Nashville warblers, American goldfinches, thrashers and many others. As I leafed through his guidebook, I knew I wanted not only to watch birds but also to know birds, to understand them.

With help, I set up birdbaths, bird feeders and suet cakes in my yard. A whole new world opened before me—the world of wings. And I wanted to find my place in it.

Living with paraplegia required incredible patience and persistence, and I was determined to apply these qualities to birdwatching. I paid laser close attention to the birds’ nest building and child-rearing, to what they ate and to their relationships with other birds. Everything concerning my new companions interested me.

I started to record sightings in a field guide of my own, and I photographed every bird I logged. Jerry was impressed with my progress. “What’s your favorite bird?” he asked.

“I count all birds as friends, but especially the small dainty ones,” I said. “Hummingbirds, chickadees, kinglets, wrens and warblers. There’s an art to photographing them that involves patience and serendipity.”

Churr-churr, queeah, called a red-bellied woodpecker, feasting on a suet cake, his red head shining in the sun’s rays. We laughed. Woodpeckers have distinct, resounding voices.

I locked my wheelchair in place, listening until the woodpecker took flight.

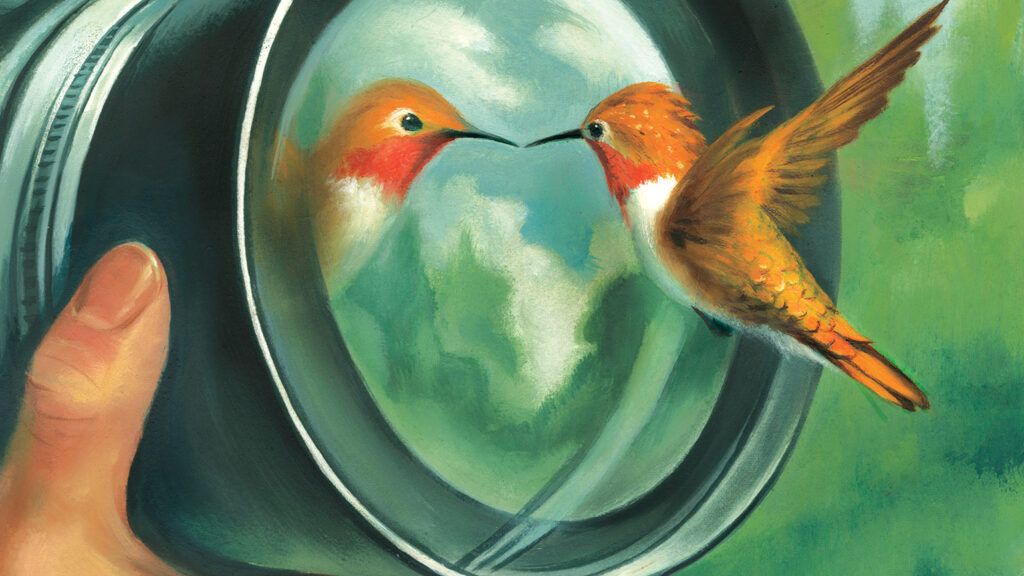

“You know, I became obsessed when I heard about that rufous hummingbird spotted in the area.”

“Yep,” Jerry said, “a rufous appearing in this region of the country is extremely rare.”

“That’s not all. While I was pondering the unlikelihood of seeing it myself, I experienced what I can only describe as a nudge, and then a knowing. I raced—and you know how fast I can wheel my chair—to the next street over, where I knew scarlet sage was growing, one of the rufous’s favorite foods. I waited and waited, camera in hand. Finally, a male rufous appeared, wearing a bronzy-copper suit and a bright red tie. I got the photograph!”

I showed Jerry the picture in my field guide. Cheer, cheer, cheer, sang a cardinal from the tallow tree. “Why, thank you, sir,” I said.

After Jerry left, I wheeled to the front of the house and spread birdseed up and down the sidewalks. It was the least I could do for these creatures who’d shown me how to be fully present in the moment.

I now slow down and savor the taste of my favorite foods. I appreciate long, meaningful talks. I’m more patient with my daughters. I feel a new kind of pleasure when tending the potted plants on my deck. And I’m alive not only to birdsong but also to the range of nature’s soundscape, like the whistle of a breeze through the leaves, the chants of tree frogs at dusk.

A few months ago, when the sun hung low in the evening sky and lingered on the tips of the mulberry tree, a male painted bunting landed on my birdfeeder. The most beautiful bird in North America was right here in my own neighborhood, with his indigo-blue head, sunset-orange breast and iridescent golden-green wings. I reached for my camera. Could such an exquisite being really belong to this world? I wondered.

Of course, I encounter hardships every day, but now when I look out my kitchen window I see birds. And when I see birds, I see earthly angels. I see miracles. And I’ve found my place among them.

For more angelic stories, subscribe to Angels on Earth magazine.