It was our third day in Prague and already we’d visited six churches. My wife, Tib, has a boundless capacity for gilded domes and rococo statuary, but as I limped painfully up the steps to Our Lady of Victory I promised myself this was my last church here in the Czech Republic.

I’d plead the inevitable stair-climbing involved; a year after knee-replacement surgery steps were still agony.

“Early baroque,” Tib read from her guidebook, “the Barefoot Carmelite order has been in residence since 1618.” Blocking the stair landing, a group of schoolgirls in green blazers were listening to a pink-cheeked nun with a marvelous Irish brogue. “Hands carved by a mysterious sculptor,” the nun was saying.

This sounded more interesting than yet another date or the weight of gold leaf on another ceiling, but the green-clad group was standing aside to let us pass.

Stepping inside we were met by an all-enveloping hush, a kind of mutually held breath, quite unlike the atmosphere in the other churches. Always there’d been the hum of voices, the clatter of footsteps, the flash of cameras. Here, in spite of the hundred or more people walking or sitting or kneeling in the sanctuary, there was a quiet that went beyond silence.

What made this place different? At first glance it was much like the others, with its elaborate high altar and painted saints. About halfway down to our right was a side altar with a curved red-marble railing at which a dozen people knelt, while 20 others waited their turn. Curious, I walked down to see what was attracting such attention.

It was the usual florid shrine, all gilt and candles and frolicking cherubs. Inside a glass-and-silver case at the center was a small wax figure in a gold-embroidered purple robe and cape, on its head a tall gem-encrusted gold crown. Amid all this finery only the chubby face and plump hands of the figure itself were visible—clearly the features of a very young child.

Only a foot and a half high, to me it looked like a doll, very much in fact like a wax-faced doll of my grandmother’s.

Its gestures, though, were anything but doll-like. The tiny right hand was raised in formal blessing; the left held a golden globe of the world topped by a cross of diamonds.

And suddenly I knew why it all seemed oddly familiar. This must be the famous Infant of Prague, whose replica even such a reluctant tourist as I had seen in many churches in many countries. Jesus, age perhaps one-and-a-half, but robed and crowned as a splendid king.

I stood in that crowd at the altar rail, puzzled by the attraction this small figure exerted even on me. We were certainly a diverse group. The street woman with her plastic bag, the soldier—German?—in uniform, the woman with the worn face, the man with the briefcase and silently moving lips. Ring binders lining the railing provided prayers in nine languages.

Different circumstances, different nations, yet each with some quality in common. Need, I thought, for money, or relationship or healing—like me with the stubborn pain in my knee.

Still, intrigued as I was, I’m not especially into dolls. With a whispered goodbye to Tib I made my way back across the Karluv Most, the 650-year-old bridge that connects the church’s neighborhood of Mala Strana to Old Town, near our hotel on the other side of the Vltava.

But I couldn’t get the little Infant out of my mind. Could those tiny hands be the ones the nun was talking about? Was there some mystery about the statue? I spent the evening studying the abundant literature Tib, as always, had brought back from the church.

No one knows when the Infant was carved. What is known is that it was brought from Spain in 1555 by a princess coming to Prague for an arranged marriage to a man she’d never met. Alone in this strange, cold country she found comfort in the little wax figure from her family chapel.

It was this princess’s daughter, Lady Polyxena of Lobkowitz, who in 1628 gave the sculpture to the Carmelites for their new church.

Just three years later Prague was invaded by Saxon troops in one of the most bloody combats of the Thirty Years War. The Carmelites were no match for sword and blunderbuss, and they fled. The occupying army seized everything of value and then destroyed what was left. For roughly six years the church was used as a warehouse.

When the monks returned they searched the despoiled sanctuary for the little statue. It had vanished, taken with the other loot, most likely, for its costly ornaments.

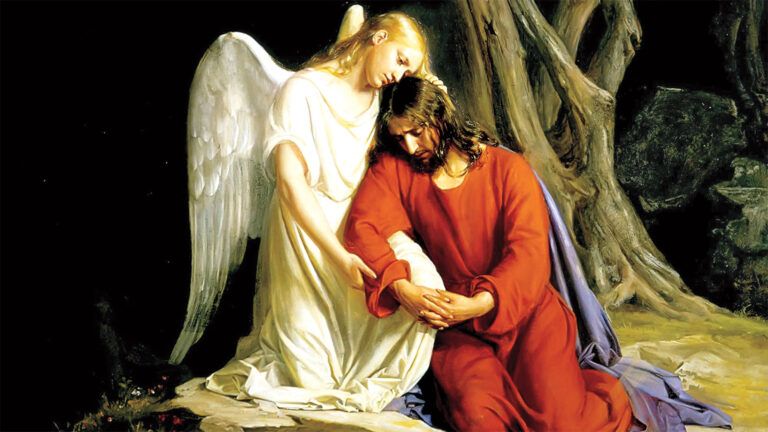

Some time later a monk named Cyril was sweeping the dusty floor behind the altar when he spotted something wedged into a corner. It was the little wax figure, stripped of its jewels. Father Cyril blew away a cloud of chalky grime and bit his lip—both of the little hands were missing.

Cyril pleaded with his superiors to hire a sculptor to repair the damaged statue. But money was scarce, and with both monastery and church left in ruins images were not a top priority. The maimed Infant was placed in an oratory inside the walls where only the Carmelites could enter.

Soon word got around that when the monks prayed there, focusing their attention on Jesus as a tiny child, their prayers were often answered in remarkable ways. Cyril hoped all the more that the Infant could get back its hands and be returned to the church, accessible to all.

One day Father Cyril was told there was someone wanting to speak to him in the church. There he found a lady kneeling in prayer at the altar. She rose to hand him a leather pouch. “The grace of God has sent you this gift to ease your heart’s desire,” she said. He opened it and saw a large sum of money.

When he looked up, the lady had disappeared. It was enough to hire the top sculptor in the city, “because work for God must be the finest there is.” But the new hands, when the fee was paid and the sculpture returned, were too big, glaringly out of proportion to the small figure.

Another sculptor was hired, but his work, when finished, could not be made to stay attached to the fragile wax arms. Yet a third tried, for a price, to carve new hands; these too fell off.

Then one day a young man came to the monastery. He’d heard about the Infant’s missing hands and wanted to repair them. The stranger offered no credentials, but running low on money the monks had no choice but to let this unknown sculptor try where experts had failed. They found a corner where the young man could work and left him alone.

The next morning when they went into the makeshift workroom they were astonished to find the statue upright on a pedestal, wax hands exquisitely fashioned and so perfectly joined to the statue that it was impossible to see where the new work began.

The monks scurried around looking for the young sculptor so they could pay him for his fine work. They searched the monastery, the church, the neighborhood. No one in the city knew where the sculptor came from or where he went. “He must be an angel,” the citizens whispered among themselves. The statue was moved back to the main sanctuary, and in time the monks were able to build a side altar to display it.

So this was the mysterious sculptor the nun had been talking about. But surely, I thought, it can’t be the little wax figure itself, no matter how curious its history, that for more than 350 years has brought pilgrims streaming to this place.

The next morning I crossed the Karluv Most with its street musicians, souvenir sellers and throngs of tourists to stand again in the back of the Carmelite church. As far down the aisle as I could see, the pew-backs were scarred with cigarette burns, perhaps a reminder of 44 years of Communist rule when churches were used as a place to house troops.

The sanctuary was as full, and as hushed, as before, the same variety of people clustered at the side altar. In the literature Tib brought back to the hotel the sculptor was again referred to as an angel. What was so important about this particular statue that even angels in heaven wanted it returned to public view?

Looking around that morning I thought I had a hint. Many of us in the church, perhaps all of us, had some circumstance we were powerless to change. Nothing I’d tried changed the fact of a painful and limiting knee.

A one-year-old child has no power either, yet this Infant was robed in victory! Perhaps that was its appeal. Look again, the angels want to say. God’s view of your situation is right in front of you.

Powerlessness is the perfect place to be—because it throws you totally into the arms of God. When you surrender your weakness to him, he turns it into a victory. Not always the victory you would have chosen, but always one that shows you a new dimension of his love.