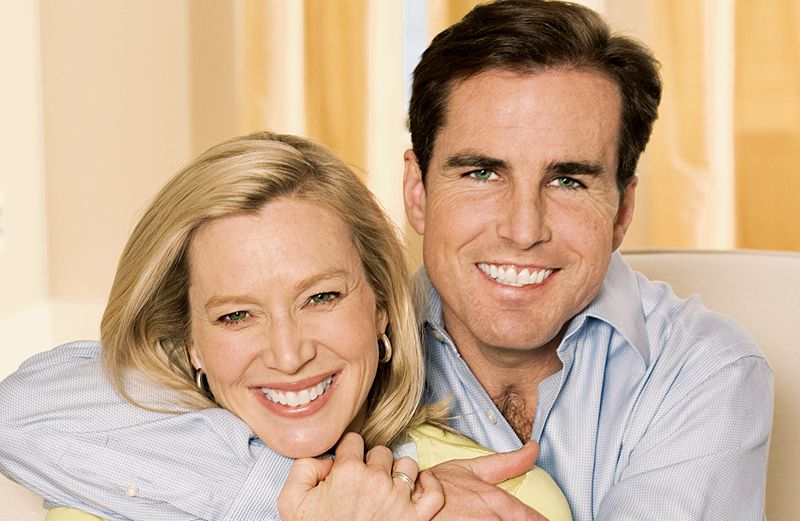

It was Bob’s fifth trip to Iraq, his first since becoming coanchor of ABC World News Tonight, and when I kissed him goodbye that morning last year, I was thinking about the exercise class I wanted to go to later that day and the logistics of taking our four kids to Disney World.

Obviously a national news anchor like Bob travels a lot, so I was used to handling things by myself. I didn’t usually worry about him. In fact, this time I didn’t really want to think of the danger he was facing at all. Better to block it all out of my mind.

Sunday morning, January 29, the call woke me up at the hotel in Disney World. It was the president of ABC News. “Lee, Bob has been wounded in Iraq,” he said, choosing his words carefully. “He’s alive but he may have taken shrapnel to the brain.”

I had to get out of that room—to think, to pray, to make some calls.

The kids were still asleep. I slipped on some clothes, grabbed my cell phone and dashed outside, my heart racing. There was a small lake outside the hotel and I set off around it at a fast pace. Part of me wanted to shout out at God, “Why us?”

Bob and I had had some tough moments in our marriage, including a time when I plunged into depression after a miscarriage. My faith had pulled me through and I was a stronger person for it.

Would the same faith sustain me now, even if the news got worse? I simply couldn’t imagine what life would be without my husband.

Cathryn, our 12-year-old, was awake when I got back inside. So was 14-year-old Mack. Mercifully the five-year-old twins were still asleep on the pullout couch.

“Guys,” I said, “Dad has been hurt in Iraq.” I told them what I’d learned, that Bob was riding in a tank with the army and something blew up, injuring him. “We don’t have a lot of information, but I know he’s getting great medical care.”

“He’s alive?” Cathryn asked, a quiver in her voice.

“Yes. They’re doing all they can for him.” Bob was being airlifted to Germany. I would go there immediately to see him. When he was stabilized, he’d come back to National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda. First we had to fly home to Westchester, outside of New York City.

I have to remain strong for our children, I told myself over and over. On the plane I fought to hide my tears. One thing at a time, I told myself. Just get everybody settled at home.

A big gray SUV pulled up in the driveway behind us when we drove in. Out stepped a friend. She already knew—and knew I had to go to Germany. She handed me a goodie bag for the plane with magazines, candy, gum, aspirin and a toothbrush. Then jumped into her car and drove away. Just like that.

It was the first indication of the huge network of friends and family that I would come to rely on over the next few months. They made Costco runs, took my children for playdates, drove them to soccer practices and confirmation classes and dropped off endless meals.

Bob’s brothers, my sisters, our parents all came and stayed with our children at various points, making it possible for me to be with Bob.

Bob was in intensive care when I got to Germany. The worst was true: The roadside IED had driven shrapnel into Bob’s head. They’d already removed half his skull to let his brain swell without crushing against the inside of the cranium and destroying brain function.

The doctors were guarded. Bob was young and in good shape, they said. He could recover. But for the first time I heard a phrase that would be repeated again and again: “It takes a long time for the brain to heal. Remember this is a marathon, not a sprint.”

Finally, I was allowed to see him. Nothing could have prepared me. He was unconscious. His head was swollen to the size of a rugby ball, deformed at the top where a piece of his skull was missing.

A ventilator tube had been inserted down his throat and all sorts of other tubes were coming out of his body, octopus-like. There were cuts and stitches on his cheeks, forehead and neck. His lips were swollen, his left eye looked like a dead fish.

I tried to convince myself that he didn’t look that bad, that this was the worst and he’d only get better from here. Then I leaned over and ever so gently kissed him through the hospital mask I wore. I spoke to him in a deliberate way that would continue for the next 35 days, hoping somehow he heard.

“I love you, sweetie. You’ve had an accident, but you’re going to be all right.”

Yet the shock of seeing my husband in that state was devastating. That roadside bomb in Iraq had ripped through all our lives. At least he’s alive, I kept telling myself. It’s a miracle that he’s alive.

I couldn’t fly with him to Bethesda, but he was given a quilt sewn by volunteers, the Heirloom Quilters Guild in West Jefferson, Ohio, signed by all the hospital staff.

Coming through customs, I had my first inkling of how fast our story had spread. I handed my passport through the Plexiglas window to the agent. She looked at it and her face softened. She squeezed my hand when she handed it back. “The nation’s thoughts and prayers are with you, Mrs. Woodruff,” she said.

What a powerful thing to hear! And how much I would need those prayers in the days and months ahead.

The routine began. At 6:30 every morning I would head over to the ICU at Bethesda from my friend’s home and check on Bob. He still hadn’t regained consciousness, though sometimes he opened his eyes.

In that overly cheery voice that a mother uses with her baby I would talk to him. I let him know about the kids. I told him stories about us, how we met and where we had lived, some of our best memories together. I brought music and had home movies for Bob to hear.

Friends had huge photos of the kids blown up and mounted them on the walls for Bob to see. His eyes were blank, but I told myself, Somewhere there’s a brain in there, healing.

Early mornings I swam at the nearby YMCA. It was like a kind of meditation, and I talked to God as I did my laps, talked to him as if he were right there in the water with me. Would I be all right? Would the kids? Could I handle whatever came next? What would Bob be like when he woke up?

“Prepare yourself, Mrs. Woodruff,” warned one doctor. “Bob will have to learn things all over again. Think of him as a baby learning to speak, then read and write….” I thought of my husband as a giant Baby Huey and was horrified.

The doctors said he might be violent, that sometimes people recovering from brain trauma hit their loved ones. They said he probably wouldn’t ever be able to do his job again. Please, God, I prayed in the waters of that pool, I want my husband back.

The e-mails, the notes, the cards kept coming. Someone sent a cross that he could hold in his hand—the clinging cross, she called it, shaped so it could be squeezed. Others sent homemade angels made out of paper clips.

They all told us they were praying for Bob, prayers made in synagogues, churches, mosques, community centers, living rooms and YMCAs. I read the notes to Bob and hung some of the cards up on the wall. When sometimes my own faith became hard to find, I felt myself draw on the faith of so many others.

There were hopeful moments, like the day Cathryn visited and kissed him. I looked at Bob’s face and saw a tear rolling down from the corner of his good eye. “He’s crying!” I shouted. He must have known his daughter was near.

One day I was sitting next to him and telling him, “I love you, I’m with you. You’re safe in a hospital in D.C.” All at once it was as if he came alive. He opened his eyes and mouth, trying to talk to me through the tracheotomy.

He pulled my hand toward him and I could swear I saw him mouth the words, “I love you, sweetie.” He became so agitated that the trache tube came out and the nurse had to give him a shot to calm him down, but I clung to that image of him trying to speak as much as I clung to the prayers on the walls around us.

In the fourth week they took out the trache tube and moved him to another ward. I had tried so hard to be strong, but I could feel my energy sagging.

On the first weekend of March, the children came to visit and when they spoke to their dad he gave no indication that he heard them. He had grown so thin and was fragile and pale, not like the daddy they remembered at all.

I missed being with them and couldn’t bear to see them go back to New York. How much longer could we go on?

Two days later I went for an early swim, as usual, then headed to Bob’s hospital room. I was thinking of the children back home, just getting up for school. I loved that moment when they just woke up from their dreams.

I pushed open the door to Bob’s room. I froze. He was sitting up in bed, a huge smile on his face. He saw me and lifted his hands in the air. “Hey, sweetie,” he said, “where have you been?”

I tried to speak but no words came out. This was so much more than I’d wanted and prayed for, that I couldn’t really believe it. My husband was back and he was calling me.

Half of me wanted to shout in relief and gratitude and half of me wanted to explain everything, how I’d been there day after day for five weeks. I dropped my coat and my swim bag to the floor and ran to him.

There were many months of therapy ahead. Bob came back to New York and spent his days as an inpatient at Columbia University Medical Center.

Sometimes he still struggled to find a word and we got really good at playing charades, but when he came up with a word like “unsettling” all on his own, I knew he was well on his way.

In May he had to have surgery—an acrylic skull plate was fused to bone where his skull was missing, to protect his brain—and he was free to go outdoors without a helmet. The old Bob was back.

Or was he? No person, no couple, no family goes through something like that without being changed and learning something about themselves they may never have learned otherwise.

Bob was fortunate. He had the best medical treatment possible, and we were blessed with the finest doctors and therapists. But the most important thing turned out to be all those prayers that held us close. I found that my faith was deepened by that fact, and that gave me strength, a greater strength than I’d ever known.

A White Light—Bob Woodruff

People ask me what I remember of the explosion. Very little.

We were filming a segment from the tank hatch. Because of the roar of the diesel engine it was hard to hear, but Doug, my cameraman, and I decided to give it a try.

We were coming to a stand of trees where insurgents were waiting. They say you never hear the bomb that hits you, and I didn’t. But I recall something even more profound. I found myself enveloped by a pure white light. It was peaceful.

My body fell back into the tank, but I floated above it in a place where there was no pain. I don’t think I even knew I’d been hit. The white light felt so good, like soft welcoming arms. Then it disappeared and I was awake on the floor of the tank.

I looked up and saw Doug arcross from me. I remember spitting blood and someone touching my head. But it’s the memory of that white light that’s clearest. I saw what I think must’ve been heaven. I can still feel its peacefulness.

Because of it, I have no fear of death now. Of course, I’d hate to leave my family, but I’m comforted by the thought of what will come next.

Download your FREE ebook, A Prayer for Every Need, by Dr. Norman Vincent Peale