George Foster Peabody was impatient to end his meeting. He was one of the richest men in the nation in 1923, a banker and philanthropist. The man in front of him was desperate to keep his 300-room inn afloat. He’d come from tiny Bullochville, in southwest Georgia, to New York City for a loan. But what did Peabody care about a down-on-its-luck resort in the middle of nowhere?

“One more thing,” the inn’s owner said. “There’s this boy. He has polio.” He told the story of Louis Joseph, whose family had brought him to swim at the inn’s naturally warmed pools for the past three summers.

“I can’t explain it,” the innkeeper said. “The boy uses two canes. But he’s walking.”

Peabody leaned forward, suddenly intrigued. “I have this friend,” he said. “This could be the news he’s been waiting for…”

The friend in question was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a man whose name was synonymous with East Coast power and privilege. Harvard-educated, he’d served as a New York state senator and assistant secretary of the Navy in the Wilson administration. Men looked up to him. Women swooned over him. His distant cousin Teddy had been a popular president, and there seemed little doubt that Roosevelt would follow in his footsteps. He’d even been preparing a run for governor of New York.

Then the unthinkable happened.

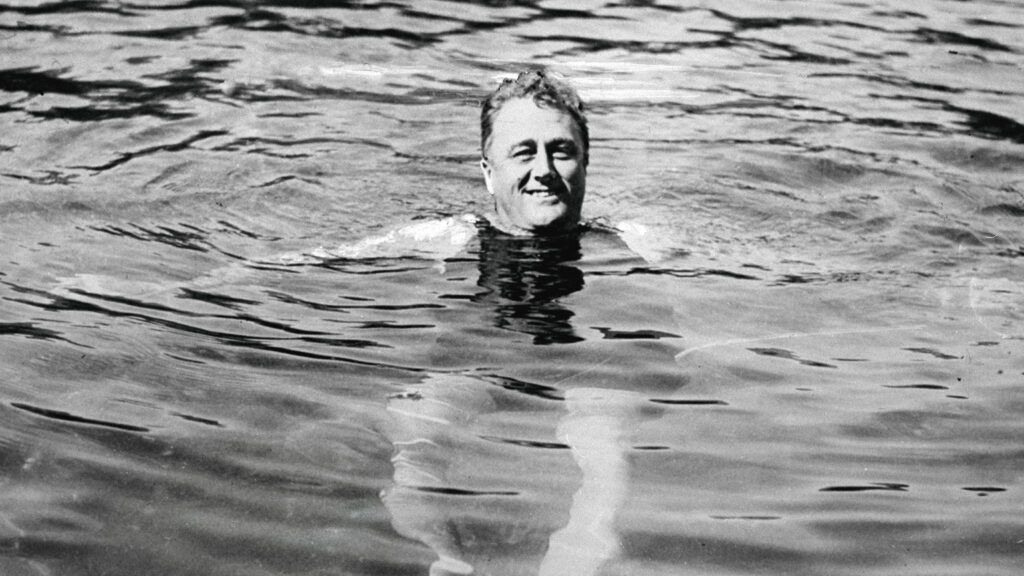

In 1921, he went sailing with his wife, Eleanor, and their five children. A day capped by a long swim in the ocean. Roosevelt was 39, in the prime of his life. But the next morning, he woke to stabbing pains in his legs. By evening, he could no longer stand. Too weak to even grip a pencil. Completely dependent on Eleanor for his care. Polio—an incurable, paralyzing virus—was sweeping the country, infecting thousands of people. Often spread through untreated sewage, it was the scourge of lower- to middle-class families. Not someone of Roosevelt’s stature. Yet, after weeks of misdiagnoses, a doctor finally broke the news: Roosevelt would never walk again.

It was a devastating blow. There was no chance, it seemed, that the onetime state senator would hold political office again. “He felt as if God had betrayed him,” says Christine Wicker, a journalist and author of the recently published The Simple Faith of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. “He went into a deep, deep depression.”

Still, Roosevelt refused to believe he would never walk again. Securing his legs with steel braces, he dragged himself, hour after hour, along parallel bars, the pain excruciating. He tried ultraviolet light, massage therapy, electric currents. He worked his muscles in warm water and cold water. He consulted with the nation’s top doctors. There was no progress. With braces and crutches, he could take only a few steps before the pain overwhelmed him.

Even so, Roosevelt stayed in the public eye. In the summer of 1924, he agreed to make the nominating speech for Al Smith, the Democratic presidential candidate. With the help of his son and a crutch under each arm, Roosevelt approached the lectern, dragging one foot after the other, to the pity of the crowd. It was later that evening that he ran into George Peabody and learned about the miraculous pools of southwest Georgia.

That’s how Roosevelt found himself in Bullochville that October. His destination—the Meriwether Inn—was a three-story monstrosity. A money pit ever since its construction in the late 1800s. And no wonder. This was an area of struggling farmers, hardly a tourist draw. Roosevelt himself would have never come if not for the inn’s pools of mineral water, pumped from nearby Pine Mountain.

Inside the inn were two small rectangular pools, and outside another pool, unremarkable in every way. News of little Louis Joseph hadn’t yet spread. And so, when Roosevelt dipped his legs into the 88-degree water, he was practically alone. In the four-foot-deep pool, he was able to stand and even take steps. Instantly energized, he splashed about for hours, carefree. And he met Louis Joseph—living proof of the answer Roosevelt had been searching for.

Folks in Bullochville were abuzz about Roosevelt’s stay. An Atlanta newspaper published a story. The following April, when Roosevelt returned, he found himself in the company of a dozen other “polios,” as they were known. Roosevelt exercised with them daily, teaching them what he’d learned, cheering them on. There was no medical staff at the Meriwether. “We’ll be our own nurses and doctors,” Roosevelt said. As Wicker tells it, every time a new polio survivor arrived, Roosevelt personally welcomed them, bringing them to the pool and doing a formal evaluation of “how each of their muscles functioned, its strength and range of motion.” Visitors started calling him Dr. Roosevelt.

More polio survivors arrived each week. Thirty-one the first year, 50 the next year and 70 the year after that. Though Roosevelt’s own progress had stalled, he found himself returning to the dilapidated inn, staying for weeks, then months, at a time. His friends, even Eleanor, couldn’t understand the appeal. But Roosevelt felt at home there. He enjoyed mingling with the other survivors, the easy banter. Some of them were getting stronger, walking even. But his interest in them was becoming less about their physical struggles and more about who they were as people.

It was as if he were seeing the world through new eyes. In 1926, he bought the Meriwether Inn for $200,000, some two thirds of his net worth. Friends warned him against it, afraid he wasn’t focusing enough on himself or finding his way back into politics. Roosevelt ignored them. Not long afterward, he led a campaign to change the town’s name to the more appealing Warm Springs.

In 1927, Roosevelt spent half the year in Georgia. It wasn’t just the polio survivors he was warming to, though more than a dozen had found jobs at the Meriwether Inn. Roosevelt tooled about the countryside in his Ford Model A, stopping to talk to farmers, tradespeople and shopkeepers. He asked about their families, crop prices, the hardships they faced. “He was always the squire,” a resident recalled in the book The Squire of Warm Springs: FDR in Georgia, 1924 to 1945, by Theo Lippman. “But he was genuinely liked and seemed to like everybody.”

Folks would volunteer how they’d been out of work, how they wished for a better life for their children, how they worried about being unable to provide for themselves in old age. Many of the homes Roosevelt visited lacked electricity. The sagging economy was already hitting people hard.

Roosevelt never found the physical healing he’d sought in Warm Springs. He spent most of his time in a wheelchair. But he wasn’t the same man who’d arrived in 1924. In the three years since, he’d come to see polio as a test of his faith. He’d found a new strength in the enduring friendships he made with people he seemingly had little in common with.

Five years later, Roosevelt was elected president in a landslide. The country was hurting from the Great Depression. But Roosevelt was specially equipped for the job. He remembered the courage, the perseverance, of the folks he’d met in Warm Springs. Fear was their biggest obstacle, one he was all too familiar with. Many New Deal programs were a direct result of the time he’d spent in Georgia. The Tennessee Valley Authority to supply electricity throughout the South. The Social Security Administration to provide a safety net for the aged. The Civilian Conservation Corps to give the unemployed work and create parks, dams and roads. All of them needs Roosevelt had encountered while driving the Georgia countryside.

“The polios came to him, weakened, their spirits crushed…,” Wicker writes. “He had no cure. Just some water and his own faith.”

In the end, it wasn’t only Roosevelt, or those affected by polio, who found hope at the inn. The faith Roosevelt gained there strengthened an entire nation to get back on its feet. An unexpected healing from the healing waters of Warm Springs.

7 of the World’s Healing Waters |