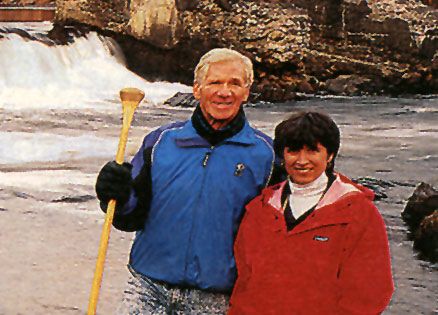

I didn't have to ask my wife, Debra, if the river was high that April afternoon; I could hear it. The two dogs barked joyfully as we unloaded our canoe from the pickup. Pee Wee, our 15-year-old sheltie, jumped around my legs like a puppy, and even Bronnie, the big German shepherd, momentarily forgot his dignity as my Seeing Eye dog and tugged eagerly at the lead.

We had never had the canoe out this early, when the Sebec was swollen with snowmelt. But on that mild spring day last year, our friends Roland and Mary Richardson had suggested an eight-mile run from our town to Milo, the next town downstream.

They pulled their canoe from the back of our truck and followed us across the road to the put-in, where the foundation of an old mill jutted into the stream. Before Bronnie had led me halfway across the old mill floor my tennis shoes were splashing through icy water. I had never known the river so full!

"At least this should make the Rips smoother going," I said. The Rips are a 300-yard stretch of boulder-strewn rapids halfway between Sebec and Milo, the only tricky bit of navigation along our route. With the river in spate, I figured all but the biggest rocks would be safely underwater.

I held the canoe steady as Debra climbed into the forward seat. I'm the stronger paddler, so I always take the steering position in back. How can a blind man steer a canoe? people ask. And what brings me out on a swift-moving, rock-strewn river anyway? The first answer is easy; Debra directs me: "Left!" or "Hard right!" Why I do it is a harder question. Maybe it's because I know what it's like to have two good eyes and still end up on the rocks.

When I was a sighted person I was an alcoholic, a dropout as a husband and father, a guy who lived only for himself. The first clear-eyed thing I had ever done was as a blind man, when I asked God to take charge of my life. I had never spent much time in his vast outdoors, but after I quit drinking I couldn't get enough of it. I learned wilderness skills and became the first blind person to "thru-hike" the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine. I made a point of telling fellow hikers about the God who guides me.

It was his world that beckoned as I took my place in the rear of the canoe, Bronnie between my knees, Pee Wee yipping excitedly up front. Then the two canoes were off along the deserted waterway. A few summer cabins, I knew, dotted the north bank, but there would be no one on this stretch of the river.

We chatted for the first few miles, before the thunder of the approaching Rips drowned out the Richardsons' voices. The current picked up till our two canoes were careening along at breakneck speed. The roar of the rapids was so loud I could barely hear Debra, just a few feet away.

Abruptly, I felt us go into a spin, whirling round and round in a dizzying eddy. The motion must have startled Pee Wee—I heard him jumping about. Between my knees Bronnie jumped too. As his 90 pounds shifted, the canoe tipped sideways, then capsized. The next instant I was tumbling and thrashing in the middle of the freezing river.

I broke through the surface, shouted Debra's name, went under again. Something kept pushing me down. It was the canoe, forcing me underwater as the current propelled it downstream. Struggling free, I thrust my head up. "Debra!"

I snatched at the canoe, but the current tore it away. I hurtled through the water, slamming into boulders, rolling and spinning. As I bumped against a rock, I managed to grab hold. At that instant I heard over the roar of the water the sweetest sound in the world. Debra calling me.

"Baby!" I yelled. "I'm over here!"

She answered something, but the noise of the river drowned it out. In the near-freezing water my hands were swiftly going numb. I let the current take my feet backward till they touched another rock downstream. Legs braced against the battering rapids, I shouted questions in the direction of Debra's voice. Though I missed much of what she said, I understood she had managed to haul herself onto a boulder, maybe five yards from the north bank.

"Have you seen Bronnie?"

"No!" she shouted back.

"Pee Wee?"

"He went under!"

Poor little fellow…Or maybe, I thought, as the icy torrent pummeled me, a swift death was easier than hypothermia's slow, inexorable shutting down. By the time I'd been in the water half an hour—I've got an uncannily accurate sense of time—my arms and legs were as numb as my hands. Milo was a good four miles away, but I was sure Roland and Mary had reached it by now. They must have realized we weren't following them. How long before they could get a rescue team organized? Maybe in time for Debra, but certainly too late for me.

Another half hour had passed when there was a cry from Debra. She saw Bronnie on the bank. Bronnie, you made it! I thought.

By then I had lost all feeling below the neck. Debra was shouting something else. "I'm going to swim for it!"

"Don't!" I pleaded. Roland and Mary must have given the alarm by now. My internal clock ticked off another hour; the sun felt lower on my face. How much longer till rescuers reached us? Debra shouted again that she could make it to shore. "No! The Richardsons have help coming!"

"But they're gone!" she cried. "I've been trying to tell you! They tipped over right after we did!"

Mary? Roland? Gone? The first warmth I had felt since the accident was my own tears on my face. There was no hope for us either. It could be weeks before anyone opened one of the summer places. The next time Debra yelled she was going to swim, I didn't argue. "Okay, Baby," I called. "I love you!"

"I love you too! Here I go!"

Lord, keep your arms around my wife! I thought.

For moments that seemed like hours there was nothing but the deafening tumult of the river. Then a joyful cry. "Bill, I made it! Bronnie's here! We're going for help!"

Four miles on a muddy logging road? "Good, Baby!" I called, though "Goodbye, Debra," was what I meant. Running would at least keep her warm, keep her from having to see me swept from my rocky handhold. The fatal stupor of hypothermia was creeping through me, numbing my mind as well as my muscles.

Debra was gone maybe 20 minutes when I lost my grip. The current whirled me downstream. A branch brushed my head and seconds later I stopped moving. There seemed to be tree limbs around me. Had I reached land? With barely any sensation in my lower legs, I pushed myself up, on my elbows, then onto my knees, until I was standing. I splashed a couple of feet forward onto flooded ground, then stopped. Directly in front of me, behind, all around, I could hear rampaging water. I must be on a tiny, half-drowned island.

A late-afternoon wind cut through my sodden clothes. My chance of survival, I knew, depended on creating body heat. Bracing my elbows on a limb, I began running in place in six inches of water. I had been at this hopeless marathon maybe an hour when above the water's roar I heard a shout from the bank. A man's voice.

"Hang on, help's coming!"

To my questions, he replied there were 30 feet of rapids between me and the shore. "Just keep running! Your wife's safe. The dogs too."

Dogs? Pee Wee made it? "What about our friends Mary and Roland?" I called to him.

"At our cabin. They're okay."

For another 45 minutes, until the local game warden reached me in a canoe tethered to shore, I ran in place on my brushwood island, every step a prayer of thanksgiving. In the emergency room at the local hospital, Mary, Roland, Debra and I pieced together the extraordinary series of events that had saved us. Fortunately, we were all okay physically.

Only two other people had been on those eight miles of river that day, a couple named Yanok who had come to open their cabin. They had been ready to leave when Albert Yanok, the man who called to me from the bank, for some reason went down to their dock. And there he had heard Mary calling for help.

She and Roland had ended up close to the Yanoks' place. Had the accident happened a minute later, had the Yanoks left a minute sooner, had Albert Yanok not been at the river's edge…

But, of course, someone else was on the river that day too. Someone who sees every picture whole. "We walk by faith, not by sight," the Bible tells us. I knew it was true for the blind, but it's also true, I learned that April day, for the sighted.