Allied bombers roared overhead. The earth shook. A-36 Apaches and Curtiss P-40 Warhawks cut across the sky over Milan leaving trails of fire streaking behind them. Dust fell from the refectory rafters of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie with every blast.

That August night in 1943, American and British troops invaded Italy, dealing a crushing blow to the Axis powers. But one of the world’s most iconic paintings was caught in the crossfire.

It would take something extraordinary, even miraculous, to protect Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, The Last Supper, on a night like this.

A firemen’s line heaved sandbags through the door of the refectory, piling them against the painting on the north wall. The sound of bombs grew closer while workers called urgently to one another. Scaffolding was constructed, and before long the disciples’ faces were hidden from the night.

The fifteenth century Grazie was not expected to withstand the force of a blast. The ancient bricks would crumble like sand.

“Uscire!” someone shouted. “Get out!” The planes were directly overhead now. Workers fled the building, the Grazie was evacuated. Alone in the refectory, one of the world’s greatest and most storied masterpieces waited out the violent night.

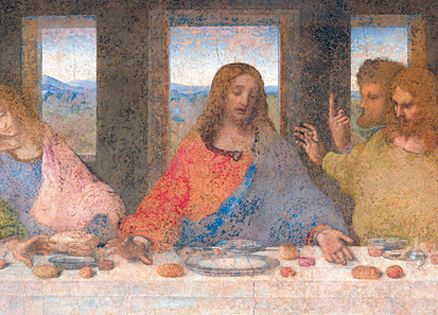

From the very beginning, da Vinci’s mural was destined to become the seminal depiction of Christ’s last supper. The beauty of the painting was evident, due to da Vinci’s renaissance-influenced perfection of geometry, perspective and light.

Legend has it that the artist spent many days walking the streets of Milan to find the perfect face and expression for each apostle. Then there was Jesus’ striking solitude in the painting—it is a rare depiction without Saint John’s head resting on Christ’s breast.

Jesus is isolated from his disciples, a poignant symbol of his impending sacrifice.

Is it any wonder that a fresco so intricate, from a venerated master like da Vinci, would inspire admirers to create their own theories and fantasies about the work’s hidden meanings?

Da Vinci began the painting in 1495, commissioned by Duke Ludovico Sforza to prepare the Grazie for the Sforza family’s burial site.

Innovator that he was, Leonardo decided that the traditional fresco painting method, buon fresco—using watercolor and tempera paints on wet plaster—resulted in colors that were too dull, too unrefined. So he devised a new method.

He sealed the plaster and used oil paint on top, which allowed for greater detail and more vibrant hues. Da Vinci labored for three years, sometimes applying only one or two brushstrokes per day, striving for a perfection commensurate with his subject.

His new painting method, however, soon proved disastrous. The layers dried unevenly and the painting began to crack before it was even finished.

Not long after the fresco’s completion, Milan was invaded by the French troops of Louis XII in the Italian War of 1499. Da Vinci was compelled to flee the city, escaping to Florence and leaving his home of 17 years. He never saw his masterpiece again.

Within 20 years, The Last Supper had already begun to flake from the wall. In 1652 a Dominican monk in his brown robes chipped away the plaster and brick. Already two centuries old, the wall came apart easily. At last there would be a doorway between the kitchen and the refectory. Hot meals! But at a high cost.

The passageway had cut the feet off of the figure of Christ. By then, though, da Vinci’s mural had already begun to fade into obscurity.

Milan was invaded by Napoleon in 1796. Napoleon’s soldiers commandeered the refectory, turning it into a barracks and a stable. They took to throwing rocks at The Last Supper. The soldiers defaced the painting, scratching out the eyes of the apostles. It was against orders, but no one bothered to enforce them.

Finally, in 1821, a restorer named Stefano Barezzi was hired to remove the entire fresco and transport it to a museum. This type of work was his specialty. But he was unaware of da Vinci’s ill-fated decision to use oil paint, not bound to the plaster but laid onto it like a canvas.

Barezzi began the delicate removal. Immediately a portion of the painting near Christ’s face collapsed. The restorer frantically attempted to repair the damage, gluing together the pieces of paint and plaster that he had crumbled. Eventually he gave up the project in despair.

Two wars, neglectful monks, rowdy soldiers, failed restoration attempts. In more than four centuries, The Last Supper suffered them all.

And now as the Second World War raged, on a night when destruction rained from the sky above Milan, the greatest and most moving depiction of Christ’s last meal was almost certain to be lost forever.

Allied bombs fell ever closer to the evacuated Grazie in a terrifying crescendo. Then, in the middle of the night, the worst happened: The convent was struck.

Walls collapsed, beams splintered, the roof caved in. Bricks were pulverized. The ancient convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie lay in ruins.

In the morning, when the bombing was over, the workers and monks returned to the convent, moving through the rubble in shock. Nothing was left save for dust and debris. Nothing, that is, except a single surviving wall.

Da Vinci’s Last Supper.

How had the bombs missed it? How had the delicate paint withstood the thunderous assault? Whole blocks of the city had been leveled. And yet….

After the war, restoration began again in earnest. In 1979, microscopic imaging detailed the damage done by years of mold and air pollution, and allowed restorers to painstakingly remove everything but da Vinci’s original paint, exposing features that had been hidden for centuries.

With such rich detail, one could imagine almost anything looking deep into Leonardo’s creation. Theories sprang up.

Had da Vinci hidden musical notes somewhere in the brushstrokes? Was the softness in the depiction of John intended to really show Mary Magdalene? Was that the holy grail on the wall behind the figure of Bartholomew?

Perhaps da Vinci was Illuminati, or a Freemason, and the whole fresco was a code to unlocking ancient secrets of the early Christian church. There was no end to the wild speculation.

Yet what we do know is this: Through the chosen hand of the greatest genius of the Renaissance, an image was created that we were never meant to forget, and its impossible survival is more than a miracle and a mystery. It is a message for all mankind.

Download your FREE ebook, Mysterious Ways: 9 Inspiring Stories that Show Evidence of God's Love and God's Grace