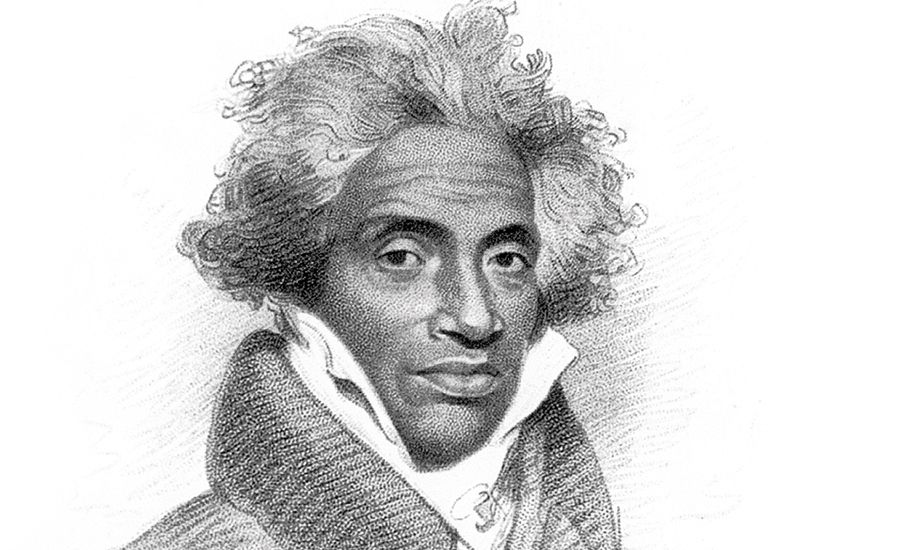

In 1781, deep in the interior of West Africa, in the town of Timbo, lived a 19-year-old prince, Abdul Rahman Ibrahima. He was a scholar and a warrior, the favored son of King Sori. He’d studied math, geography and Arabic in Timbuktu so he could read the Koran, committing long passages to memory. As a soldier he had recently won an important battle for his father, bringing peace to the realm.

Meanwhile on the coast an Irish doctor, John Cox, left his ship to go hunting. He got separated from his party and wandered further and further inland. By the time Ibrahima’s people found him, he had collapsed, sick from the bite of a poisonous worm. He was brought to King Sori who investigated the wound and urged him to stay until he recovered, offering him a house and a nurse.

Dr. Cox stayed for six months in Timbo, befriending Ibrahima. He even taught him a little English. Finally well enough to travel, Dr. Cox bid the young prince good-bye, the two assuming they’d never see each other again. King Sori gave Cox a new set of clothes, some gold for expenses and 15 warriors to protect him as he made his way back to the coast.

In Timbo, Ibrahima continued to thrive under his father’s favor and was given greater command in his father’s army. In 1788, at age 26, he led his troops into battle and was captured. He pleaded with his captors to ransom him, claiming he would be worth more than 100 head of cattle and a man’s weight in gold, but they opted to sell him to slave traders for a mere pittance—gunpowder, muskets, tobacco and rum.

The prince was clapped in chains and shipped to America. There he was taken up the Mississippi River to Natchez and sold to Thomas Foster, a tobacco farmer his own age.

Even after months of humiliation and a hellish journey crammed in a slave ship where he couldn’t stand upright, Ibrahima remembered who he was and who his father was. He explained to his master that he was a prince and that his father would pay untold amounts for his freedom. Whether Foster believed him or not, he needed a slave for his farm. His only concession was to give Ibrahima the name Prince. But Ibrahima hated the name. It was a mockery.

While enslaved, Ibrahima married an enslaved woman named Isabella and they had children. The couple marketed their own produce in town and even kept profits for themselves. But Ibrahima was not free. He was certain he would never see his homeland again.

Ibrahima yearned for home and liberty and attempted to run away. He came back and worked as Foster’s slave for decades, but as Terry Alford’s excellent biography, Prince Among Slaves, notes, he was never seen smiling.

Ibrahima had no time to read or study and he wasn’t allowed books anyway. And yet he never forgot who he was in Timbo, and was seen tracing Arabic characters in the sand when there was a break in the work—a word or two of sacred verses, recalling his study of the Koran.

Then one day in 1807, Ibrahima was sent to town to sell some produce. A white man on horseback approached him. Ibrahima offered him sweet potatoes. The man on horseback studied Ibrahima’s face with his one good eye. “Where are you from?” he asked.

“From Africa,” Ibrahima answered.

“You came from Timbo?” the white man asked. Yes, he came from Timbo. Yes, his name was Ibrahima. And did he know whom he was speaking to? Yes, he knew very well; it was Dr. Cox, the Irishman who had stayed with his family, recovering from his illness, who had even taught him some English.

Twenty-six years after they first encountered each other, 5,500 miles away, the two happened to meet in a dusty Mississippi town—the prince and the man who owed his very survival to the prince’s father.

Dr. Cox hastened to meet Thomas Foster and did all he could to buy Ibrahima’s freedom, offering huge sums, money he could ill afford to part with. He’d been in a couple of shipwrecks, emigrated to the United States, practiced medicine on the frontier, lost money in bad investments and come to Mississippi to start over.

No matter what he offered, Foster would not accept it. He needed Ibrahima—now his overseer—too much. Foster said he couldn’t do without him. Dr. Cox died before he could buy Ibrahima’s freedom.

So how did his story come to light? Why is his name not lost to memory, just another of the millions of enslaved people brought to America? Others claimed to have noble backgrounds and their stories died with them. Such is the horrific nature of slavery—it robs people of their identity.

Fortunately, Dr. Cox’s efforts brought Ibrahima’s plight to the attention of abolitionists and the United States government. Secretary of State Henry Clay, an enslaver himself, was moved by the story of Dr. Cox and Ibrahima, and finally bought Ibrahima’s freedom.

By then Ibrahima was an old man, although hardly broken in spirit. In 1828 he launched a lecture tour across the country, trying to raise money for his children’s freedom, and the following year, he returned to Africa, to the new country of Liberia, founded as a home for once-enslaved Americans who had become free.

Tragically, Ibrahima never made it back to his home in Timbo. He passed away only months after his return to the continent. However, more than a century later, his legacy and his unlikely encounters with Dr. Cox live on in his descendants.

Dr. Artemus Gaye, Ibrahima’s seventh-great grandson, left Liberia after that country’s civil war and is now a professor of ethics at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Illinois. He only recently learned of his princely ancestor, when he began digging into his genealogy.

“The story sounded impossible,” Dr. Gaye said to me. “For anyone to escape the evil of slavery was a tremendous struggle. Ibrahima could have been another one of the forgotten, erased from history. Instead, here I am, to tell his story and carry on his name.”

Download your FREE ebook, Mysterious Ways: 9 Inspiring Stories that Show Evidence of God’s Love and God’s Grace.