In a past issue of Mysterious Ways, I wrote about one of the “thin places” in the world, the Italian town of Assisi, where the membrane between heaven and earth seems diaphanous. When we published that story, some of us asked, was it possible that some people might have the same capacity, seeing visions of the spiritual universe as though it were the everyday?

We didn’t have to look far, for there on the magazine’s back cover was a quote from William Blake, the mystical British poet and artist of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.”

Community Newsletter

Get More Inspiration Delivered to Your Inbox

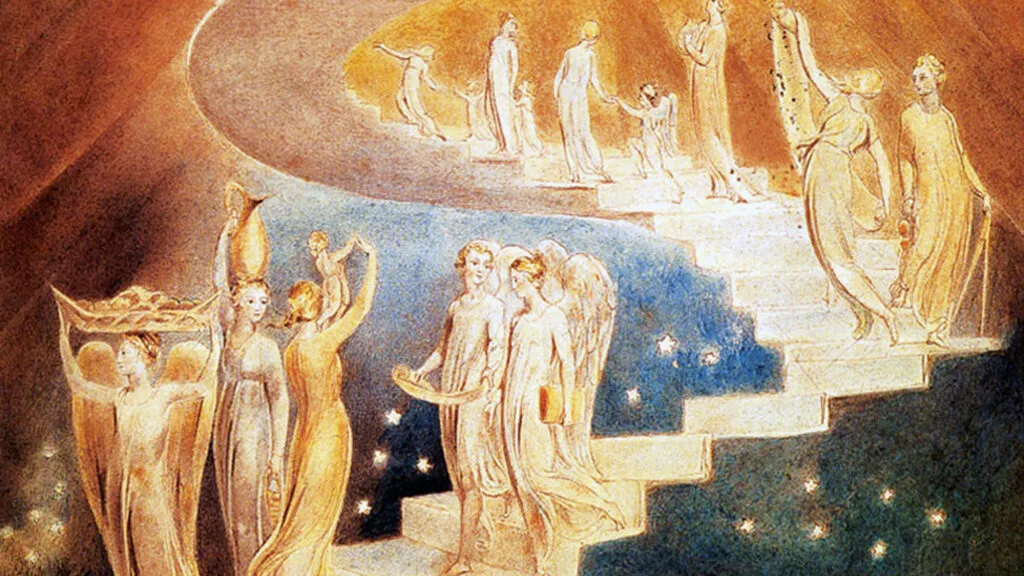

Narrow chinks of a cavern versus doors thrown wide open to the infinite. No doubt about it, Blake’s brilliantly colored paintings and profound poems reveal the sensibility of an artist engrossed in the world beyond: angels, demons, prophets, Jesus, God. His doors of perception were flung open. He always claimed he painted and drew what he did because that’s exactly what he saw. It was his reality. And those unearthly poems? Sometimes they came so fast to his pen because he was simply transcribing what a heavenly voice whispered in his ear. But he was also grounded in the real world, working hard as a printer and engraver.

Born in London to a working-class family, he lived almost his entire life in the teeming, pestilential city. For him it shimmered with the possibilities of a new Jerusalem. The most important book in the Blake household was the Bible, and the stories of the Bible, especially its imagery of cherubim, trumpets, prophets, stars and spears, lions and lambs, crowded his imagination. He would have heard that “Our God is a consuming fire” (Hebrews 12:29), so that when—as he later explained—at age four he saw God peering in his second-floor window, he did the only natural thing: He screamed in terror.

He loved to wander through the wooded hills on the outskirts of town. On a boyhood jaunt through an open area called Peckham Rye, he saw a vision of angels in a tree, their wings fluttering in the boughs. Incapable of keeping such an apparition to himself, he rushed home and told his parents. His father threatened to throttle him for lying, or indulging in some fantasy, but his mother was quite convinced of her son’s honesty and moved by his innocence. Later he baffled his contemporaries with his visionary talk, but he never felt constrained to edit himself. If he had seen God or angels or the prophet Ezekiel under a tree, as he once did, it should be reported. Why keep such glories a secret?

The great tragedy of his life was the loss of his younger brother, Robert, who died at age 19 from consumption. Blake had hardly left his brother’s bedside, nursing him, devastated at the anticipated loss. How could he go on without his beloved Robert? And yet, at the very end he observed Robert’s soul leaving its body and “clapping its hands for joy.” The moment confirmed for Blake that death was not an end in itself but a journey to another world, one that he felt he could reach out and touch.

Even after Robert’s death, Blake felt his brother close by. “With his spirit I converse daily and hourly in the spirit & see him in my remembrance,” Blake wrote. “I hear his advice & even now write from his dictate.” That phrase “in the spirit” is important. Blake was not claiming to see a ghost but was receiving messages from a loved one in God’s realm. The sort of comforting presence that countless others have found in grief, except heightened by a man who kept his doors of perception wide open.

Once when he was struggling with a perplexing problem in the engraving business, wondering how he could print a poem with a colored image cheaply, he received a vision of Robert taking on the task. With great thoroughness Robert performed all the steps, revealed the ink to use, the method. Was a vision ever more practical? Blake sent his wife out with half a crown to buy the necessary materials. The method, as described, worked perfectly.

As he grew older and his poetry and art grew more idiosyncratic—and more superb—Blake faced criticism and became increasingly remote from the world. “I am in God’s presence night & day,” he scrawled on a notebook page. In his late sixties his health began to fail, but he worked till the end, illustrating the Bible and Dante, working continually on a big painting of the Last Judgment. Among the last things he bought was a new pencil.

A friend of his observed, “Just before he died, his countenance became fair. His eyes brighten’d and he burst out into singing of the things he saw in Heaven.”

Today Blake’s prints, sketches and paintings of those visions are in the world’s finest museums. His poems are included in countless anthologies. He is a widely accepted mystic—and regarded by some as mad. But he was never institutionalized like his contemporary the poet William Cowper (who coined the phase mysterious ways), nor did he indulge in drugs, like Samuel Coleridge. His doors of perception were ones he felt all of us could open. If we let ourselves see what he saw, our world could be transformed too.