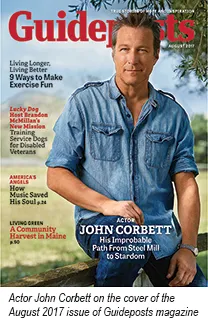

Most of my career I’ve played the nice guy, the romantic interest with a heart of gold. I’m really comfortable in those supporting roles. So my role in the new movie All Saints, as an Episcopal priest who’s assigned to a small church in Smyrna, Tennessee, was a definite challenge. Not that Michael Spurlock, who’s a real person—the movie is inspired by a true story—isn’t a good guy. But I’d never played the lead, a character who’s on every page of the script, and it scared me. Yet something made me say yes to it.

Not quite. Refugees from Burma show up. There are 70 of them, members of the Karen ethnic group and observant Anglicans. They want to be part of the church. But their needs go beyond the spiritual. They need jobs, food, places to live.

Michael reaches out to them, even though he’s not going to be around long enough to make much difference. As soon as he sells the church’s acreage, he’ll be gone. But then God gives him an idea. The Karen people were farmers back in Burma. What if they farmed the land the church owned? They could grow their own food, sell the extra produce and maybe even help raise money to pay off the church’s debt.

That’s exactly what happened. It’s not what Michael Spurlock expected; it’s not what his superiors had asked for; it’s not at all what he’d been assigned to do. Except it’s exactly what God wanted.

That really spoke to me because there have been times in my own life I’ve ended up doing something I totally didn’t expect, something I couldn’t even have imagined. Flash back to the first half of my life. Not long after I was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, my parents moved our little family to California. They split up when I was two, and my mom and I took the train back to Wheeling to live with her mother. It was a great place to grow up. I went to a small Catholic school with the same 13 kids from first through eighth grade, then the Catholic high school on the same block. Everybody knew everybody.

Weekdays and Sundays I served as an altar boy at St. Joseph’s Cathedral, a big beautiful place with a dome, mosaics, a massive pipe organ and an immense circular stained-glass window. I got up at 5 a.m. to do my paper route, then rushed to church. Altar boys had to be on their toes, putting on vestments, stacking hymnals, arranging the wafers, filling the water and wine cruets, lining up the bells. No sleeping on your feet. By the time I was 15, I’d worked so many funerals that an open casket hardly fazed me (being slipped a fiver as a tip wasn’t so bad either).

I learned self-discipline as an altar boy. It was good training for a guy who would end up making movies—not that I had the slightest inkling of my path back then.

I figured I’d just stick around Wheeling after high school and get a job. I wasn’t cut out for college; I was a C or D student at best. My dad drove out from Southern California for my high school graduation. He asked me what I planned to do with my life. I shrugged. I didn’t know.

“If you ever want to work in the steel industry,” Dad said, “I can help you find a job.” He was a welder. “Just let me know.”

“Sure,” I said, never thinking I’d take him up on it. I’d grown up all the way across the country, so I didn’t really know him well.

A couple of months later, making only $2.65 an hour as a delivery boy, I found the offer more tempting. Maybe I should try California. Maybe a job like Dad’s would be just the ticket. I drove out there with some buddies. I didn’t even tell my dad I was coming. In fact, I didn’t even know where he lived, just the name of the town. Bellflower.

I took a bus to Bellflower. I went to a phone booth outside a Laundromat, looked up “John M. Corbett” in the book and found his address. There was a guy putting laundry into his hatchback. I told him the address and asked, “Can you tell me where this is?”

“About a mile from here.” He started to give me directions, but he must have seen how clueless I was. “Let me take you there,” he said.

I got in his hatchback, and he drove to a small two-bedroom house. I knocked on the door. My dad and his wife welcomed me in, and I stayed for a year. True to his word, Dad got me a job at Kaiser Steel in Fontana. Soon I was earning more money than I’d ever dreamed, clocking 60-hour weeks. I had a nice apartment, nice clothes and plenty of money to go out with my buddies. The work, though, was grueling.

I wanted to believe there was something else out there for me, something I was meant to do, but I had no idea what it was. Year in, year out, I stuck it out in that open-ended factory, freezing in the winter, when the wind howled down the San Bernardino Mountains, sweltering in the summer.

Then one day some pipes came off the assembly line and hit me in the back. Next thing I knew, I was on disability, walking with a cane, popping painkillers.

Manual labor was out of the question. What was I going to do with myself now? “Why don’t you go to community college?” Dad said. “Take some classes. Get a degree.” I’d been such a lousy student. What purpose would college serve? Then again, it wasn’t as if anything else was jumping out at me.

The first week at Cerritos College went okay. The second week, the assignments came. Read eight chapters by tomorrow. Write a five-page paper. I was completely lost. One afternoon I stayed in the cafeteria long after everybody else left, totally disheartened. College was a dead end for me. Twenty-four years old and I had no future.

I finished my chicken burger and was picking at some French fries when a few guys came in and sat at the other end of the long table, 18-year-olds just out of high school. They were joking around. I made some jokes back. They laughed and scooted over to me. I asked what classes they were taking. “Acting,” they said. Who knew there were acting classes at Cerritos?

“We’ve got an improv class next,” they said. “Wanna come?”

“Your teacher won’t mind?”

“No. Come on.”

I grabbed my cane and hobbled after them. They took me to a theater that was like a black box: black bleachers, black floor, black floor-to-ceiling curtains and a small performing area. It had a mysterious, almost mystical feel. The instructor walked in. Georgia Well was her name. My new friends introduced me. “This is John. Okay if he stays?”

“Sure,” she said. I watched one improv after another. I’d never been around anything like this! It was as if a whole new world opened up to me, a world I longed to be a part of, a world where I sensed I belonged. It was as clear as anything I’d ever gleaned from those hours on my feet at St. Joseph’s, listening to the priest.

To my surprise, Georgia Well asked if I wanted to do an improv. I knew enough to know I had to say yes, yes to a new purpose for me, a new understanding of myself. I wanted to be here, take acting classes, learn to do all the things my new friends did, perform in plays (not that I’d ever seen one).

I dropped my other classes and signed up for all the acting classes at Cerritos. Within a month, I’d landed a role in the campus production of Hair. My dad’s jaw just about dropped to the floor when he saw me on stage singing. Everything on his face said, I didn’t know you could do this. I didn’t know I could do it either!

That’s what happens when you follow God’s lead and do what brings you joy. I didn’t need the cane or the painkillers anymore. Healing came from the work I was doing, the friends, the new passion I’d discovered. I’m the least likely guy to end up in several hit TV series, let alone star in a Hollywood movie. Me, a blue-collar kid from West Virginia. But when I look back, I can see how the altar boy duties, the paper route, Dad’s finding me a job at a steel mill, even the debilitating back injury brought me to where I am now.

Still, I can’t help asking myself, What if I hadn’t been sitting in the cafeteria that day? What if I hadn’t gone with those guys to that improv class?

I’ve learned, like the priest I play in All Saints, that when God sends a suggestion our way, the best thing we can do for ourselves is say yes.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.