For years, mom and I had talked about writing a book together. A book about ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging. A big coffee table book with beautiful pictures of flowers, like the calla lily and fern she’d arranged at the alter for my wedding. Mom said calla lilies were a symbol of holiness, faith and purity. The book would have been full of the information she conveyed so well, as she did at the ikebana class she taught for my friends in California while we awaited the birth of my oldest daughter.

But we never wrote that book. My mother has Alzheimer’s. She was diagnosed in 2011, though some signs appeared even before then. There is nothing good about Alzheimer’s. It’s not a disease where you can make lemonade from lemons. It steals our memories, and what are we without our memories?

But my mother has taught me that, in the midst of loss, there is indestructible spirit. There is beauty. And always love.

Though she has forgotten so much, sometimes even the names and faces of her children, much of her personality is intact. She still likes polite children and beds that are made. She loves birds and classical music, the Beach Boys and Petula Clark. She is neat, almost prim, and she has a passion for flowers. She also still loves ikebana, something she came to master when we were stationed in Yokohama, Japan, where my father had been sent to command a ship during the Vietnam War.

I was the middle of five—children, mind you, not kids. As my mom said, kids was a name for goats. In many ways, my parents were polar opposites: Mom, the delicate Dallas lady, and Dad, the rough-and-tumble El Paso cowboy turned naval officer. But they were also the yin to each other’s yang. I often wonder how she did it all, raising us on her own while Dad was away at sea for long stretches of time.

In Japan, we drank powdered milk from the commissary. We did our homework and got good grades, or else we would be in trouble. We were allowed five minutes each on the hallway phone (and my sisters and I never called boys). We took ballet and charcoal drawing classes and said our “hallowed be thy name” prayers. We learned to sew. There was no TV, so we read books and listened to Harry Belafonte as we waited for Dad to return.

Mother took a class in ikebana and fell in love with its discipline, its colors and fragrances and the waxy flowers and leaves. She would place arrangements throughout the house. After school, we were greeted by flowers. Pink gladiolus nestled between limegreen bamboo shoots, erupting from a low olive vase. As Mom explained, they were arranged to form a simple triangle symbolizing heaven, earth and man—or shin, soe and hikae in Japanese.

Unlike the Western tradition of plunking hothouse blossoms in a vase, ikebana allows you to gather cuttings, what’s known as line material, from whatever is in season. Pussy willow, palm and pine, draping jasmine and cherry blossom, forsythia, wisteria— Mother used all of them. Ikebana originated with monks arranging flowers at temples, and I don’t doubt that the meditative quality is what drew Mom to it. Ikebana gave her time to pause and reflect on beauty, nature and God.

and siblings.

She always marked the holidays. We had green pancakes on St. Patrick’s Day. A Little Debbie Oatmeal Creme Pie appeared in our brown-bag lunches on Valentine’s Day, along with a heart-shaped card of red construction paper and a note declaring her love for us.

My favorite valentine was a folded red heart with a wrapped piece of Wrigley’s spearmint chewing gum glued to the front of it. Inside the card, Mom had written “I’m stuck on you” (she loved puns). After lunch in the schoolyard, I snuck the gum in my mouth and chewed, savoring the love of my mom. I didn’t even spit it out that night when I went to bed. In the morning, there was a sticky mess of chewing gum in my hair and Mom had to cut it out—a little less stuck on me then.

She helped me get my start as a professional actor. I’d graduated from the University of Texas with a theater major and moved to Washington, D.C. My plan was to audition for plays in the D.C. area and get my union card, then move to New York. But I had to pay the rent, so I worked in a parking garage by day and waitressed at night.

One day, when I was visiting my parents in their Virginia home, Mom pulled out a newspaper article. “Look, dear,” she said, “there are auditions at the Little Theatre of Old Town Alexandria for I Ought to Be in Pictures.”

“It’s a musical, Mom.”

“No, honey,” she said, “It says it’s a play by Neil Simon.”

We went back and forth, me insisting it was a musical, she pointing out the role of Libby, the adolescent daughter. Finally I gave in and went. And got the part—no singing required. I got good reviews and made a brag sheet of them that I showed around. I got another play and more good reviews. And a union card. All because my mother wouldn’t give up on me.

When I made it to New York, Mom helped me move into a fifth-floor walkup. At night, we climbed the rickety fire escape to the rooftop to gaze at the sky, our heads back, our eyes wide, our mouths full of prayers. On Sundays we went to Marble Collegiate Church to hear Arthur Caliandro preach and get books and tapes of Norman Vincent Peale’s sermons. On one spring visit, we bought some forsythia at the corner deli and Mom made a beautiful arrangement with that triangle of earth, heaven and man—shin, soe and hikae—mimicking that starry night sky. By then, she was a real force in the ikebana world, having revived the Fort Worth chapter almost single-handedly.

She and Dad were with me when I accepted my Oscar for best supporting actress, playing Lee Krasner, the wife of painter Jackson Pollock in the movie Pollock. It wasn’t hard to find them from the stage. Dad was standing up, his arms over his head, bellowing “Bravo!” He was crying, and Mom was crying and trying to pull him down by his tuxedo jacket. Later that night, I put the Oscar on the coffee table in our hotel room and got down on my knees to say a prayer of gratitude.

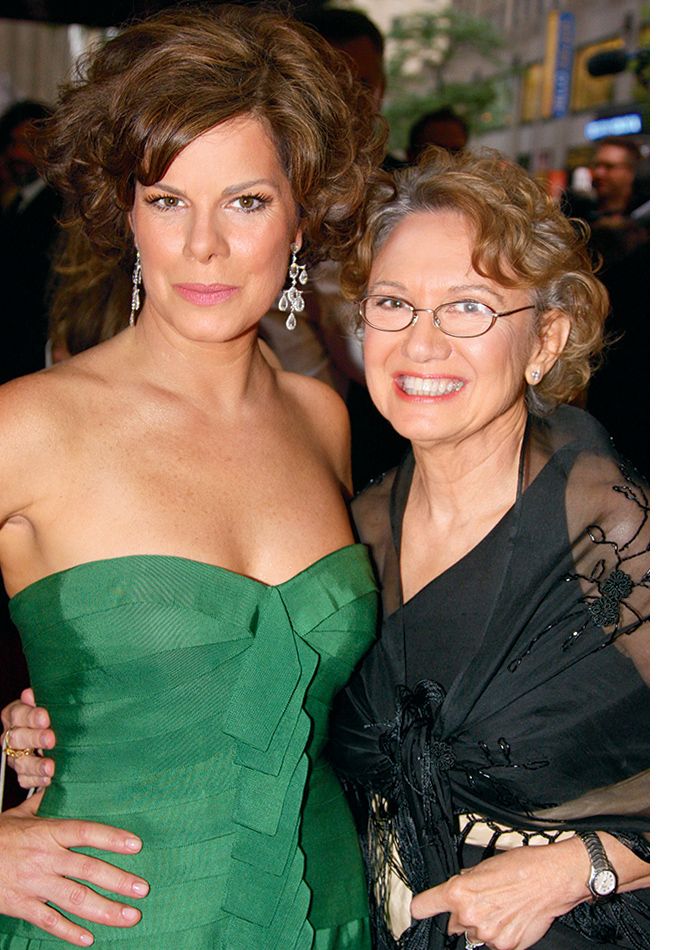

After Dad’s death, Mom was often my companion on the red carpet. She loved to travel and took delight in the pampering that came with getting our hair and makeup done. We were on the plane for one of those Hollywood junkets when I saw the first sign of something amiss. She put her passport in her purse and minutes later went to check it, not remembering where it was. This happened several times before the plane even took off. “Something is wrong, Marcia,” she said. “I shouldn’t keep forgetting this.”

before the Tony Awards in 2009.

At another junket a couple years later, there were two back-to-back events, the press night and the premiere. Mom kept getting confused about which dress she was supposed to wear for which event. She came to my hotel room and said she couldn’t remember if that night was the press night or the premiere. She was embarrassed and panicky. In that instant, I realized she wasn’t sure if the evening before had already passed without her having any memory of it.

She rallied, but I was devastated. I couldn’t bear to think of her with Alzheimer’s. She was supposed to grow old as gracefully as she had already lived, like one of her flower arrangements. I slept with her in her hotel room—I didn’t want her to be alone or confused when she woke up. I thought of the Valentine’s Day spearmint gum and wanted to be a piece of gum to stick the pieces of her memory back together.

We sold my mother’s Fort Worth house in anticipation of the mounting costs of caregiving. She now lives in a smaller, comfortable ranch-style house. It doesn’t have her plants, her pyracantha or American beautyberry, but she is near doctors and a church, near my sisters—who shower Mom with love and visits—and near caregivers who take wonderful, exacting care of her. But the change has depressed us, and the inability to do much, to do more, has darkened my spirit.

The moment came that I’d expected and dreaded—when she didn’t remember me. It was a simple conversation. We were on the phone discussing my children’s spring break from school and whether I would be able to make it to Texas or if I would take the kids (kids!) to Hawaii. Her reply, “I’m sorry, but who are you?” was surely harder for her than it was for me. I was prepared for it; it had been coming on gradually.

“It’s okay if you don’t remember me,” I said. “I will always remember you.”

Not long ago, I was FaceTiming with her, and I could tell that she started to say something and then stopped. “God…,” she said.

“Do you think about God?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“What do you think about God?”

“Love,” she said. “Love. It happens to everyone. The better the thoughts, the better the thinking.” When all is said and done, what exists is love. It transcends place and time, like the beauty of a flower. And it is indestructible.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.

|

Check out Marcia Gay Harden’s new book, |