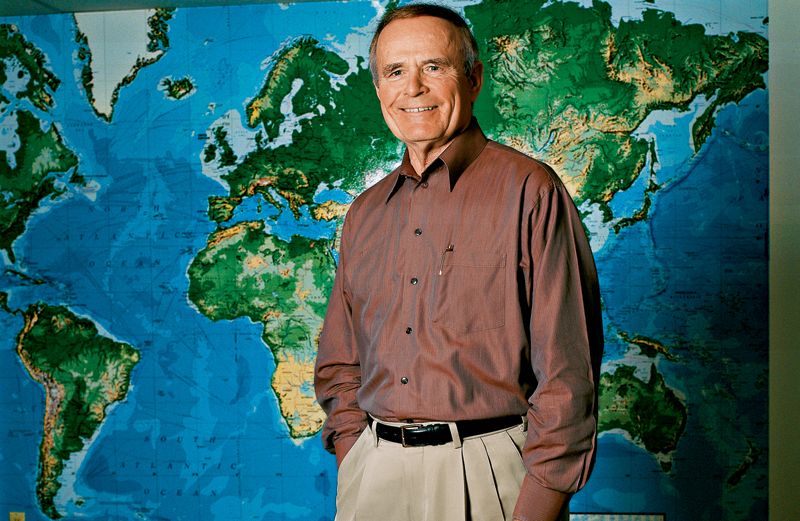

Visit our headquarters at CURE International, a nonprofit organization I founded to build hospitals in developing countries, and you might think you’re in any small American office.

We’ve got computers, a postage meter, a conference room with a map of the world. Faxes fly and donations of medical equipment arrive by the truckload.

But at the very center of our operation, there’s one room with nothing more than a pew and walls lined with pictures of doctors and pastors to remind us to pray for those who minister day in and day out. I want to tell you about that room. First, though, I’ll tell you a little more about CURE.

Twenty years back I was just a surgeon in private practice. I was proud of my medical career, yet I yearned to do something more. My wife, Sally, and I prayed about it every morning at the breakfast table in our old Pennsylvania farmhouse and talked about it at church.

Out of the blue one day I received an invitation to volunteer for a month in Malawi, a small landlocked country in southeast Africa. I did some research. Malawi was one of the poorest places on earth. I was shocked to learn that there was only one orthopedic surgeon for every nine million people.

Lord, I asked, is this the answer to our prayers? Malawi?

Sally and I packed for a month, yet the number of patients needing surgery could have kept me busy for years. One of the first was a man so bent over that his chest sat on his hips. He dragged himself forward with a tree-limb crutch.

From his X rays it was clear that I could help him with the sort of spinal surgery that was relatively routine back in Harrisburg.

“What do you think?” I asked the anesthesiologist who, like me, had just arrived. We checked out the equipment in the operating room. He picked up one of the tubes he’d need. It crumbled in his hands.

“We’ll find something that works,” he promised. We needed to wait a couple of days for two units of blood to arrive. What if I fail? I didn’t want to be known as the American doctor who killed his first patient. They would never trust me, or any doctor, again.

I reviewed my medical texts. The night before surgery, Sally and I prayed together.

I had expected the operation to take four hours, but amazingly we were done in almost half that. The facilities were rough and bare, but things went well. The man was wheeled into a recovery room. I waited for a few hours to check his neurologic status.

“Move your toes,” I said. He couldn’t. To my horror he was paralyzed from the waist down.

Lord, I asked desperately, what did I do wrong? Was I overconfident? Had I not listened closely enough? Was Africa where I was meant to be? Yet the message I got back was clear–the surgery was successful and the man would be okay.

The next morning I stopped at his bed. This time I moved his toes for him. “Can you tell me which way your toes are pointing?” “Up,” he said. “And now?” “Down,” he replied. Good. Every day after that, there was improvement.

Later, after the month was up and Sally and I returned to Pennsylvania, I got the incredible news that the man had walked out of that hospital under his own power and was much better.

I told my church family all about it. “Thanks for your prayers,” I said. “If I ever go back to Africa, you can be sure we’ll need them as much as ever.”

Fourteen months later we did return to Malawi, for another stint at the same hospital. I was grateful to be back and was very eager to perform as many surgeries as I could in my short time there. But a lot had changed.

This was the late eighties. AIDS was ravaging Africa and there was virtually no treatment. I knew I had to be extra vigilant about the risks of infection both in surgery and between patients. I brought latex gloves with me and made sure I changed pairs before each patient.

The hospital had no way of testing to see if the patients were HIV positive so I had to be incredibly careful with everyone.

One busy morning I was performing hip surgery on a young woman who was infected with a venereal disease; most likely she was HIV positive too. That morning in the operating room I had a group of student doctors watching me. I described how the surgery would help. All at once, one of her blood vessels burst.

“When this happens, and you don’t have the necessary equipment, you can pinch the vessel between your fingers until it clots,” I explained while demonstrating. “Look at the clock on the wall and tell me when ten minutes are up. By then I should be able to let go of the vessel.”

We talked for what seemed to be 10 minutes, then I turned back to the clock. The hands hadn’t even moved. “It appears, Sir,” one of the student doctors said hesitatingly, “that the clock doesn’t work.”

“We’ll just wait a few more minutes to be safe,” I said, “then I’ll let go.”

Finally I removed my hand. The vessel looked fine. But there was a gaping hole in one finger of the right glove. As luck would have it, I’d cut that very finger that morning. I took the glove off. The skin on my hand was covered in blood. I was certain I was infected.

Nothing could be done about it. Not a thing. It would be two months before a test would reveal if I was HIV positive. I returned to America wondering if I faced a death sentence.

I told our congregation about what had happened. Clair, a middle-school music teacher, came up to me afterward. “You know,” he said, “while you and Sally were gone I promised myself I’d pray. I kept putting it off until one day in band practice.

“Suddenly I knew I had to pray for you. The feeling was so strong I asked one of the other teachers to take over my class. I went into the teachers’ conference room and prayed for about ten minutes–until I got a feeling that the danger had passed.”

“When was this?” I asked.

“That same day you were doing surgery. The oddest thing too, Scott. That whole time I had this image of a huge clock on a white wall. The hands weren’t moving. All I could see was the motionless clock.”

Clair was one of the first people I told, after Sally, when the tests showed I was not HIV positive. My prayer had been answered. I was certain that I was to continue my work as a surgeon so that I could volunteer in Africa.

Then in 1990 the board of a large orthopedics company asked me to become its CEO. I wasn’t tempted, even if I were well compensated. The business was struggling. If I took the job I’d be so busy I’d never have time to go to Africa. The decision was a no-brainer.

One day I was talking to our pastor and he said, “Have you prayed about it?”

“No, but it really seems like the wrong choice for me right now…” I said.

“Don’t you think you should pray first before you make that assumption?”

I was stopped dead in my tracks. “I guess so,” I said rather meekly. My pastor bowed his head and we prayed together. God’s answer was as clear to me as that feeling Sally and I had had with my first patient in Malawi, as definitive as the HIV test results. I had to take on this job.

The next four years were some of the toughest, most challenging I’d ever faced. The stress in the boardroom was equal to anything I’d ever experienced in the operating room. I learned what it was like to be answerable to a board, to stockholders, to your own employees. I discovered the importance of consensus and cooperation.

When the company was finally sold and I left, I had a different set of skills than I’d ever anticipated. Leadership skills I had never consciously set out to acquire.

Now I was financially free to give more time in Africa, but I kept wondering: Was there something else God wanted me to do? After all, I’d become a businessman only at his urging.

I did a lot of listening for his guidance–at that kitchen table, by my bed, in operating rooms in Africa. Gradually the vision for CURE took shape. We would build hospitals where they were needed most, with the best equipment we could find and the finest doctors available.

We’d start in Africa. Our hospitals would not only treat patients but train medical personnel, for that is the most underlying need in many impoverished countries. At the center of all we did there would always be prayer.

And that’s why we have that prayer chapel in our office. That’s why we look for prayers as much as we look for donations.

When I’m facing one of the challenges of running a nonprofit organization with hospitals in places like Uganda, Malawi and Afghanistan, you know you’ll find me with my head bowed. It’s the only way to run an organization–or a life.

Download your FREE ebook, A Prayer for Every Need, by Dr. Norman Vincent Peale