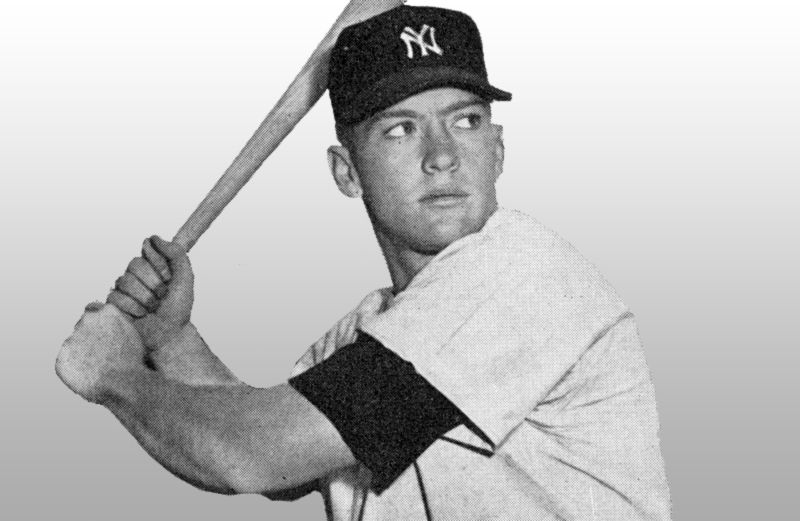

Last April 17th I knocked a baseball out of Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. I’ll not try and kid anybody by saying I didn’t realize it was a long home run.

My teammates beat my back black and blue and “atta boyed” me all over the place. They compared the drive with ones slugged by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio and big people like that.

My folks back home in Commerce, Oklahoma, soon heard about it. When Mama telephoned that night, I gabbed first with her, then with my wife Merlyn, my three brothers, kid sister, and the neighbors who happened to drop in.

Frankly, I liked all these goings on, and there was no sleep in me that night. So I tuned in several sports programs, and they were talking about my homer. Then one announcer made me cry.

He mentioned my dad, Elven Charles “Mutt” Mantle.

This broadcaster recalled how my Dad taught me to hit both lefty and righty at the age of five, and how he raised me to become a professional ball player. What he didn’t tell was how Dad tried to teach me to be a Big Leaguer off the diamond as well as on it.

While he was alive, I was Dad’s life. Now, making good for Dad is my life. I guess that sounds a little strange, and maybe it is. Perhaps it may also sound strange that I still talk to “Mutt” Mantle, my father. That night in my hotel room I asked him:

“How about it? They say it went 565 feet.”

Dad liked it but he wasn’t satisfied. Now, don’t get sore at him. He was just that way; he always demanded that I do better.

“It should have gone 600 feet,” he said … inside me.

“Okay, okay, give me time,” I said, and I’m sure he grinned.

I recalled when Dad drove me back home from Joplin, Mo., after I completed my first full year in the Class C Western Association. That was in September of 1950, and I was feeling pretty good for an 18-year-old. I batted .383, was plenty swelled up about it, and so began fishing for a compliment.

“How about that .383 average, huh?”

Dad never took his eyes off the road. “You should have hit .400,” he said. And I thought I saw him grin just a little then too.

Demanding better than good was Dad’s way of telling me there’s always a bigger Umpire than the man in blue on the field, and He’s the real judge of what you do. My father tried to model my baseball techniques from the start as a writer works on a novel, or a composer on a symphony.

I was named Mickey Charles; Mickey after Mickey Cochrane, the great Philadelphia Athletics catcher, and Charles after my grandfather. Dad and Grandpa both played sandlot baseball.

According to Mama I was in the cradle when Dad asked her to make a baseball hat for me. When I was five he had her cut down his baseball pants and sew together my first uniform. He labored practically all his short life as a lead and zinc miner.

Anyway, I was five when he began teaching me how to switch-hit. Dad was a left-hander; Grandpa, a righthander. Every day after work they’d start a five-hour batting session.

Both would toss tennis balls at me in our front yard as hard as they could. I’d bat right-handed against Dad, and switch to left-handed against Grandpa. A grounder or pop-up was an out. A drive off the side of the house was a double, off the roof a triple, a homer when I hit over the house or somebody’s window.

I’m probably the only kid around who made his old man proud of him by breaking windows.

Dad hammered baseball into me for recreation, sure. But it was more than that. He was teaching me confidence by having unlimited faith in me. Dad was 35 and I was 15 when we played week-ends for the Spavinaw, Oklahoma, team. He pitched and I played shortstop.

Those games are the most cherished of my life. Bigger than any World Series. Why? Because we played together, and I watched Dad’s faith in action.

He was never angry. He was always patient. He was unhappy when anybody made an error, even on the opposing team. He didn’t try to outshine everybody else. He just tried to shine in himself.

In high school he wasn’t happy about my playing basketball and football too. During a scrimmage one afternoon I got a kick in the left shin. I hardly noticed it, though I did limp home.

The next morning my leg was twice its normal size and discolored. There was no x-ray equipment in Commerce, so Dad borrowed the money, and got me to a specialist in Picher, Oklahoma. On the way I could see him sort of whispering to himself. He was praying.

The doctor diagnosed my trouble as osteomyelitis, a bad bone disease.

Dad borrowed up to his neck and hustled me to a clinic in Oklahoma City. There was even talk the leg would have to be amputated. When I thought it would make me give up baseball I almost went crazy. More for Dad’s sake than mine. But Mama, Dad and Grandpa all hung on. They made me hang on.

Know what saved that leg?

Prayer and penicillin.

When I got to recovering real good, I began swinging a sledgehammer at odd jobs and worked in the lead and zinc mines with Dad to put on weight and muscle. In a little over a year, I added eight inches and 40 pounds. One day in 1949, on the day I was graduated from high school, Dad said to me:

“Get me a few hits for a graduation present.”

I sure tried, and I got him a single, double, and a homer.

Dad didn’t tell me that a New York Yankee scout named Tom Greenwade was out there watching. After the game, I was signed first to the Independence, Kansas team, then to Joplin, both Yankee farm clubs. During the 1951 spring training season, I was brought up for a try-out with the Yankees!

Here was the chance to show everything Dad taught me. But how my teeth rattled! And how hard it was to control my anger. If I’d go without base hits for several days, I’d smash my knuckles against the concrete wall in the dugout, or hurt my toes kicking the water cooler. And after the game I’d ask Dad:

“What’s the matter with me? What do I do wrong?”

“Bottle up your anger, boy,” he’d say. “Let your bat do the talking for you.”

That’s the way he always was. Gentle and patient.

I started the season as a right fielder for the Yankees. I’d flash sometimes, more often I fizzled. Then in a double-header at Boston I struck out five times in a row.

I cried like a baby. “Put someone in my place who can hit the ball,” I blubbered to Manager Stengel.

Soon after this I was shipped back to Kansas City for more “seasoning.”

“I guess I don’t have it as a Big Leaguer,” I told Dad when I met him in Kansas City. “I belong in the minors.”

First he whispered silently to himself, and then he said: “Mickey, things get tough at times and you must learn to take it. If that’s all the guts you got, you don’t belong in baseball.”

His face was white and drawn. Dad had cancer, but I didn’t know it.

He left. I stayed. I did some whispering too. On my knees. And I dug in. I got to hitting again. Before the season was out Mr. Stengel brought me back to the Yankees.

Seeing me start in the World Series was probably the proudest moment of Dad’s life. In the second game I fell chasing a fly, ripped the ligaments in my right knee, and had to sit out the Series in a hospital bed. But it was all right. Dad was with me. He left a sick bed to see the Series.

“My back is acting up,” he alibied, “but now I have to watch that knee of yours.”

Then a doctor in the hospital told me Dad had cancer.

I guess I really woke up after Dad died. I mean I really got his message. Not because I had the responsibility and became the head of the family, looking after my mother and brothers and sister, and my wife. I guess I woke up to what he meant to teach me all the time.

And I thank the Lord for Dad even though He did take him away at the age of 40.

There’s been a Micky Mantle, Jr. around since last May. He doesn’t know it, but he owns a ball, bat, and glove. It’s all right with me if some more little Mantles come along in the future.

And some day I’m going to build a baseball park in Commerce, free to all, for every kid in town. It will be named Mutt Mantle Field, a sort of shrine for my father, who is still teaching me how to be a Big Leaguer—in the real sense.

Read more Guideposts Classics!