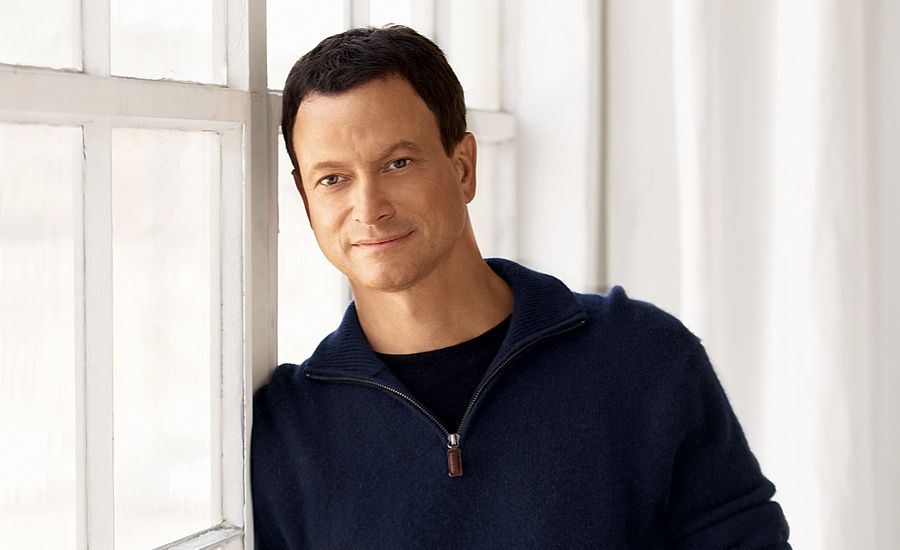

I’ve played a lot of characters in my more than 30 years as a professional actor, and I’m proud to say a fair number of them have been members of the military. Not a week goes by that someone doesn’t refer to me as “Lieutenant Dan,” the Vietnam veteran I portrayed in Forrest Gump.

For the past several years, I’ve been Detective Mac Taylor, an emotionally wounded ex-Marine, on CSI: NY.

Through my work as an actor, tours with the USO and a charity organization I cofounded called Operation Iraqi Children, I’ve been fortunate to have plenty of firsthand contact with our men and women in uniform. I can’t say enough about their commitment and courage. Here are just a few things knowing them has taught me:

ENJOYING THIS STORY? SUBSCRIBE TO GUIDEPOSTS MAGAZINE!

Be grateful.

I was a teen during the Vietnam War. While kids just a few years older than me were off fighting in that brutal conflict, I was growing up in suburban Chicago, playing bass, singing in bands with my buddies and performing in school plays.

I saw the news reports about the war on TV and joined an antiwar rally once at my high school—really just to get out of class. I didn’t have much of a clue about what was going on over there.

I turned 18 as the war was drawing to a close. I was never into school, so college wasn’t for me. I wanted to do theater. I got together with a friend from high school, Jeff Perry, and his friend Terry Kinney, and we started the Steppenwolf Theater Company.

Things fell into place, especially after I contacted the local Chamber of Commerce about finding a space for our fledgling group. They told me about a vacant Catholic school basement that used to be a teen center. “I’ll lease it to you for a dollar a year,” the priest told me. We built an 88-seat theater in that space and slowly built a following.

When I was 25 I saw a play called Tracers in Los Angeles in which real Vietnam vets relived their experiences. I sat in the audience transfixed. It was one of the most powerful things I’d ever seen. Later I thought about what I’d been doing when I was 18 and 19, how oblivious I was to what guys my age were going through.

I decided to direct a production of the play at Steppenwolf. I had only two vets in my cast and wanted to get a better understanding of the Vietnam experience, so we visited the VA hospital to talk to vets struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder. The battles they described, the haunted look in their eyes—couldn’t get them out of my mind.

The worst part was hearing how some people at home had treated them. “I was afraid to wear my uniform in public,” one vet said.

I realized how lucky I’d been to have so many opportunities while guys and gals like them had made huge sacrifices, only to be treated with contempt instead of honor. I got involved with vets groups and causes.

My wife, Moira, an actress at Steppenwolf, had brothers who were vets. I talked to them about their experiences. Time and again I thought, We have not been grateful enough for our soldiers.

By the time I read the script of Forrest Gump in 1993, I understood immediately the feelings of bitterness and hurt that Lt. Dan’s character wrestled with. Portraying him felt like something I was meant to do, like paying a debt of gratitude.

I’m grateful I had the chance. Grateful I earned a supporting actor Oscar nomination for the role. Grateful to marry Moira and be raising our three teens in this country. And most grateful that there are so many men and women who put their lives on the line to defend it.

Sacrifice.

On September 11, 2001, I realized—just like millions of you did—how vulnerable our country really is. I wanted to do something to support our troops, so I signed up for the USO shortly after our forces landed in Afghanistan.

My first overseas USO trip was to Iraq in June 2003. More than 180 people were on that tour—actors, comedians, football players, rappers, you name it.

This was my first encounter with so many active-duty military members. I must’ve shaken thousands of hands—there’d be a petite woman from the Philippines, a huge guy from Georgia, a man from Colombia, a woman from Korea—all of them serving proudly as Americans. I can’t think of a better example of what our country is all about—so many incredible people serving our country.

I was especially impressed by our military doctors caring not only for our soldiers but also the locals. On a USO tour to Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan I talked to our doctors who’d just performed brain surgery on a little girl injured by a land mine. The moment was heartbreaking and inspiring.

I’d always had a fear of hospitals going back to when I was a teen and my grandmother was dying. The gray hallways, the sterile hospital smell, the sadness on the faces in the waiting room—all of it made me want to turn around.

The worst part was seeing my grandmother lying in bed, just a shadow of her former self. I reached for her hand and it felt so brittle. I hated to see her that way. I couldn’t bring myself to go back, and had done my best to avoid hospitals.

So I was a little worried when asked to visit wounded soldiers at Landstuhl Medical Center in Germany, in 2003. But I told myself, Think of what they’ve sacrificed for me. Now it’s my turn to help them.

The first ward I walked into was full of banged-up guys. They weren’t disabled, but there were plenty of bandages to go around. The room was quiet and I was unsure of how to get started. So I just went up to a soldier and held out my hand. “I’m Gary. How are you?”

Another soldier hobbled over. “Hey, Lt. Dan, pleased to meet ya.” Soon there was a group around me, chatting about themselves and their families. Remember, it’s not about you. It’s about them, I reminded myself.

I went upstairs to another large room, this one filled with soldiers who’d lost arms or legs. There’s no way to see that and not be moved. I got so wrapped up in their stories I forgot about my awkwardness. Leaving the hospital, I felt like I’d made a difference, if only for a few minutes, in the war-torn lives of those guys—like I was being used by a power bigger than myself to give them hope.

Since then, I’ve visited wounded soldiers several times—at National Naval Medical Center, Walter Reed Army Medical Center and abroad. Each time I do, their selflessness reminds me that our country—vulnerable as it is—is served by noble men and women willing to make the ultimate sacrifice.

Reach out.

My second visit to Iraq was in November 2003 with a smaller USO tour. We went to Camp Anaconda in Balad, north of Baghdad. One afternoon the troops took a few of us—including me, Wayne Newton, Chris Isaak and Neal McCoy—to a school the troops had helped rebuild.

Even rebuilt, the school was modest by American standards. Tables and benches filled a tiny room with nothing on the walls but flies. Yet it struck me that the kids were just the same as American kids—goofy and giggling and excited about the distraction we provided. They also seemed genuinely fond of our guys—hugging them and calling them by name.

The kids sat four at a desk. One scribbled something in a small, weathered notebook. Then he handed his stubby pencil to the kid next to him. The second child scrawled something, then passed the pencil to the next boy. That’s all they have to write with. Three kids were sharing a pencil so small most Americans would have thrown it away.

I asked one of our guys about it. “There aren’t enough school supplies. They’ll be using that pencil till it won’t write anymore,” he told me.

Back in the States, I couldn’t shake that image from my mind. Our troops had done so much good at that school already. Maybe I could help them do more by sending donated school supplies.

I told someone at Camp Anaconda my idea. She suggested that I contact author Laura Hillenbrand. “She’s working on a project, getting Arabic translations of her book Seabiscuit for the kids. They’re fascinated by the story. Maybe you two could collaborate,” she said.

I talked to Laura on the phone, and Operation Iraqi Children (OIC) was born—a charity to help our troops spread much-needed supplies and goodwill to Iraqi schoolchildren.

I showed a videotape of the Iraqi school I’d visited at my own kids’ school. They used to complain about how little they had at their small Catholic school. Now they looked around at the posters on their wall, the computers, the carpet on the floor.

In January 2004 their school sent 25 boxes of supplies to Iraq—the first official OIC shipment. Today, OIC has sent more than 300,000 school-supply kits to Iraq and Afghanistan. Stuffed animals and toys often go out with the pencils and notebooks in the kits. I always knew Americans were generous—but Laura and I have been overwhelmed by the support we’ve gotten.

I hope to go back to Iraq soon to visit one of the schools. War is a terrible thing, and so often, the children pay the highest price. And they don’t understand what the fighting is about—just like I didn’t understand when I was a kid. But OIC is about finding something positive and helping our troops feel they’re doing some good. Even if it’s just one pencil at a time.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.