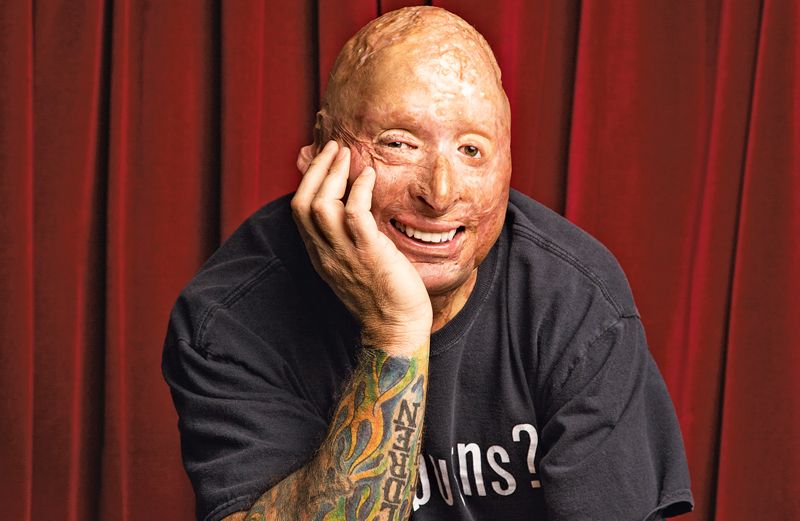

It’s hard to miss my scars. One ear is gone, the other is mangled, my bald head is a patchwork of skin grafts and my left arm ends in a stump. How did I end up like this? I tell folks it took four tours in Iraq for me to realize that my lucky number is three. Funny, right?

Don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing funny about what happened to me, but laughter has helped me heal. And it’s made me realize that how I look isn’t really what’s changed the most.

Why did I survive? Eight months after the explosion, I lay awake in bed next to my wife, Connie, that question hammering away at me.

Donate gift subscriptions to Guideposts’ Military Subscription Program

The day before Easter in 2007, I was three weeks into my fourth deployment as an Army staff sergeant and transportation specialist. My unit, D Troop, 5-73rd of the 82nd Airborne Division, was prepping for a supply run to a base north of Baghdad.

At the end of the briefing, they bowed their heads and said a prayer. Hurry up with this God stuff, I thought. I had no use for someone who wasn’t in the here and now.

We got in our Humvee and rolled out. That’s the last thing I remember.

I wasn’t one of those guys who was gung-ho Army from the day he could walk. I grew up in San Jose, California, a Navy brat. And a rebel. I wasn’t into school. Or church. The idea of some unseen being telling us what to do with our lives–that didn’t make sense to me.

The main thing I was into was partying. I drank, smoked weed, dropped out of high school. My uncle, who’s six years older, set me straight when I was 17. “I’m joining the Army,” he said. “You’d better sign up with me if you know what’s good for you.” Deep down, I did. I knew I was in trouble.

I served in Desert Storm, then mustered out. I went back to California and worked different jobs–radio deejay, truck driver, railroad maintenance man. One night I met Connie, a medical biller. Gorgeous and smart. Our birthdays were a day apart, we’d grown up one town over from each other, loved the same music.

The only thing we didn’t have in common was faith. “I feel God’s presence all the time,” Connie told me.

“Not me,” I said. “I don’t buy that whole God thing.” I couldn’t understand why someone as smart as Connie did, but that didn’t stop me from falling in love.

We married, bought a house, started a family. Life was good, and I was content. Then September 11, 2001, happened. I may have been a bit of a cynic but I was a patriot. I reenlisted. Connie understood. That October, at age 30, I went through basic training again, then airborne school, and straight to the 82nd.

Serving my country gave me a sense of purpose my civilian jobs hadn’t. I did a second tour in Iraq. A third. In 2007, I was called for my fourth. That fateful Saturday, April 7, my buddies and I got into our Humvee and headed out on our supply run.

The next thing I remember, I was standing on top of what looked to be a giant iceberg, except it wasn’t cold. The sky was an inky black, dotted with stars. I heard voices, like in a choir. Not singing, though. Chanting. “You’re going to be okay.” “Hold on.”

I didn’t recognize the voices, yet I’d never felt so loved, so at peace. If I believed in heaven, this is what it would be like, I thought. I didn’t want to leave. But the voices chanted, “Your family is waiting for you,” and I knew I was being sent back.

Then came another voice. “Can you hear me? What is your name?” I forced my eyes open. I was lying in a bed, a doctor leaning over me.

“Staff Sergeant Bobby Henline,” I rasped. Why was it so hard to speak?

Bring faith and inspiration to our troops! Donate a Guideposts subscription now

A woman stepped close. Connie! “Thank God,” she said. “I’ve been praying you’d wake up. You were in a terrible accident.”

Connie told me I was at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. Insurgents had buried an improvised explosive device in the road. The blast was so powerful it threw our Humvee five car-lengths away, where it burst into flames.

Almost 40 percent of my body had been burned. I’d been in a medically induced coma for two weeks.

Connie held a mirror up. My head was seared down to my skull. My ears looked melted. Surprisingly, I didn’t flip out. I don’t know how, but I still saw the old me in there.

“The guys?” I asked. I had to know.

“I’m so sorry,” Connie said, shaking her head. My body wanted to buck and flail in anger but I could barely move.

What the heck was that whole deal on the iceberg, then? If it was supposed to be some vision of heaven–if there even was a heaven–why weren’t my buddies there? If there was a God, why didn’t he save them?

The four of them were the ones who believed. They were kids compared to me, with their lives ahead of them. After four tours, I was practically asking to die. Why me? Why did I survive? I had no right!

Guilt gnawed at me the six months I was in the hospital. Kept eating at me after we moved our family to San Antonio to be close to a burn center. Connie left her job to become my fulltime caregiver.

The slightest infection could have killed me, so she had to dress my wounds–it took almost six hours–before we went to one of my appointments. And there were plenty: social worker, burn specialist, physical therapist, occupational therapist.

Our teenager daughter, Brittany, was a huge help, with me and with our younger kids, Skylar and McKenzie. I was in no shape to go over homework or play catch. I couldn’t even tie my own shoes.

It was obvious that everyone would be better off without me. Not that I said that–I knew they’d freak–but I kept thinking, I’m no good to anyone.

Like now, lying awake while Connie slept. Why did I survive? Why did I have that strange vision on the iceberg? I couldn’t stand it anymore. “God, if you are real, just take me,” I whispered. “Do everyone a favor.”

The next morning, I woke, still breathing. That night I asked the same thing. Again I woke up. For a month straight I demanded that God take me, yet I kept waking up every morning.

This is like some weird test of wills, I thought. That’s when it hit me: Keeping me here, that had to be God’s will. It definitely wasn’t what I wanted. Which meant God was probably real. And he wasn’t finished with me yet. But what the heck did he want?

So I took things day by day. I stopped asking to die. A year after the explosion I was able to drive again. I took the girls to the mall and Skylar to paintball with his friends. Everywhere we went people stared, then looked away. That upset the kids, but I shrugged it off. I figured folks didn’t know how to approach me.

So I wore funny T-shirts (like one that says Got Burns?). I’d smile at people and say hey. That usually got them to respond. Talking to them made me realize how much I missed hanging out with my Army buddies, just joking around. Sometimes humor was the only way we could cope with the constant danger.

That was one thing the explosion hadn’t destroyed: my sense of humor. I deployed it. During one occupational-therapy session, I cracked, “I’ve done four tours in Iraq, but that last one? It was a real blast.”

My therapist laughed.

I kept going. “Last night my wife and I were in a restaurant and she ordered a steak. I told the waiter, ‘She wants it well done. Like her man.’”

“You should be a stand-up comedian,” my OT said.

“Get up in front of strangers?” I shook my head. “I’ll stick to telling jokes to people I know. Besides, I’m going away for a while. I have to go to Los Angeles for skin-graft surgery.”

“Perfect,” she said. “My sister lives in L.A., right near the Comedy Store. She’ll help you get in.”

My OT bugged me about it until finally I said I’d give it a shot as long as she never asked me about it again.

I told Connie. She teased, “I don’t know. You’re funny, but not that funny.” I came up with some jokes and tried them out on her and the kids. They loved my routine. Would anyone else?

My OT’s sister got me a three-minute gig for open-mike night at the Comedy Store. I stepped onstage, looked at the audience–three of my friends and some comedians–and paused. Then said, “You should see the other guy.”

I got a few chuckles. But I didn’t get much of a reaction for the rest of my set. Oh, well, I thought. I bombed. Good word choice, considering, right?

Backstage a comedian said she liked one of my jokes. “Don’t give up,” she said. “You’re funny.”

Hey! I’d clicked with someone who didn’t know me. I wrote more jokes and tried them out in a comedy club back in San Antonio. “I love the Fourth of July,” I told the audience. “I go up to the fireworks stands and say, ‘Give me the same stuff you gave me last year. It was great!’”

The crowd went wild. Being up there was invigorating–reaching people in the audience, making them laugh. I booked another gig.

I get it, God, I thought. This is the new mission you have for me. Make people laugh and forget their troubles. Laughter helped me forget about mine and remember what mattered more–connecting with people.

These days you can find me performing at comedy clubs across the country, for veterans’ groups and for troops overseas. You’ll also find me sitting next to Connie at church.

I still have tough days, days when that question haunts me: Why did I survive? Why me and not my buddies? But someday I’ll see them again–in a place of infinite love and peace–and maybe we’ll look up at the starry sky and figure out the answer.

Until then, I know God’s with me in the here and now, as real as it gets. And that’s no joke.

Donate gift subscriptions to Guideposts Military Subscription Program!