This story originally appeared in the June 1985 issue of Guideposts.

I got my greetings from President Roosevelt in 1942, He invited me to join his fighting force. At the time I was a rodeo rider and cowboy. I gladly accepted Franklin D.’s invite, figuring that in his army I might get paid better,

I reported to Camp Roberts in California, where I went through 19 weeks of basic training and graduated as an Army rifleman. I was 31 years old.

Taking a “delayed route” to my next assignment, I hitched up to Oregon for one last rodeo, The rodeo announcer, the great Able Lefton, made a big deal out of me. “Here’s a genuine G.I. rodeo rider. What a patriot!” The whole crowd stood and cheered me. As I sat on a terrible bucking horse, a woman draped a U.S. flag over my shoulders. The gate opened and the horse flew out. A picture in next day’s paper showed me and the flag hitting terra firma. Bucked off. So much for the great rodeo soldier.

Next stop was Camp Meade in Maryland for more infantry training. Then to England, where I was assigned to Company K, 115th Battalion of the 29th Division. The 29th was an assault division, and every day we assaulted the southwest coast of England. Practicing. We lived in tents. Was it ever wet!

We knew we were about to open a Second Front, but we didn’t know when or where. Meanwhile German bombers and Stukas attacked us all the time.

I was scared, sure, but I also felt that my fate was out of my hands. It was in the hands of superiors. They ordered and instructed and disciplined me every minute of every day. As a cowboy I’d had to be self-reliant. That sounds nice, but it’s often a headache, For a change I had somebody else always telling me my next step. Part of me bristled, but a bigger part of me was relieved.

On the night of June 5th, 1944, I was handed real ammunition and real grenades for the first time. I knew the real thing was about to happen.

On the open deck of a troopship I rode in darkness, out into the English Channel. All I could think of was German submarines and mines. No one talked much. The sea was rough. Allied bombers droned back and forth from France.

My regiment wasn’t in the very first Normandy assault wave. During the morning of June 6th we sat at sea, while Navy destroyers fired thousands of shells at the mainland. A horrible racket. In the late morning I finally scurried down a rope ladder, then jumped into a heaving landing craft.

In the flat-bottomed L.C. we all kept tow. Many got sick. Rumor spread that the L.C. pilots were all from Father Flanagan’s Boys Town. I still don’t know if this rumor was true, but at the time it made me feel better.

When the L.C. ramp let down, the war really began for me. I jumped into the water expecting it to be shallow, but it came up to my chin. Thrashing to shore I lost my rifle and helmet.

By the time I was on the sand of Omaha Beach I’d lost my squad. I tried to burrow in, like a mole, thinking, Where’s Sergeant? Where’s Lieutenant?

Both of them were already killed, though I didn’t know it then. Just about witless, I grabbed the helmet and rifle of a guy lying dead beside me. Here on Omaha Beach there were already a thousand men killed.

Bunkered German 88 guns and machine guns poured fire on us. An American officer scampered by in a crouch, ordering me to “get going up that bluff, Private!”

I moved slowly ahead, and met up with a few guys from my squad. They were glad to see me. I was quite a bit older. And wiser … or so they thought. Crawling, I led them toward a German machine-gun nest.

By nightfall we were on the top of the bluff. The Germans had fallen back, though not far. Their rear artillery was still in place, blasting at us.

Chaos reigned all through the night. For the next few days, in fact, we couldn’t find a command post, although one officer did come along and promote me from buck private to buck sergeant.

Otherwise, my squad and I were on our own. We didn’t sleep for two or three weeks, didn’t bathe, lived on what German food we could find. The Normandy countryside was a nightmare: hedges, dikes, sunken roads and flooded fields. I never knew where the Germans would be and I got few specific orders. Find Germans and fight them. That was the basic idea.

I felt so alone. That was the worst thing. In England I’d felt part of a huge fighting force, presided over by all sorts of knowledgeable brass. But no more. Just ten of us pinned against a stone wall God knew where. No pillars of strength to lean on now. Where do you turn for strength so far from home?

I had no answer to this question. I kept fighting as hard as I could. By now we’d fought our way to the outskirts of St. Lô, France. It was early July and the summer heat had set in. One hot day, near the village of St. Claire, our company was pinned down in a flax field. My squad got awfully thirsty. I said I’d go for water. I ran underneath the fire, scrambled over a dike, and then was fairly safe.

Catching my breath below the dike, I saw a big old roan horse, just standing in the grass 20 feet away. I guessed he was a German draft horse, because the Germans still used horses to tow artillery.

I walked up to the horse. He was gentle and just looked at me. I made a bridle out of my G.I. belt and then mounted the old fellow. A ways on I found two five-gallon G.I. cans and with another belt slung them over the roan’s shoulders. I was glad to be on a horse again. I rode to a farmhouse, filled the cans from a well, gave the horse a drink.

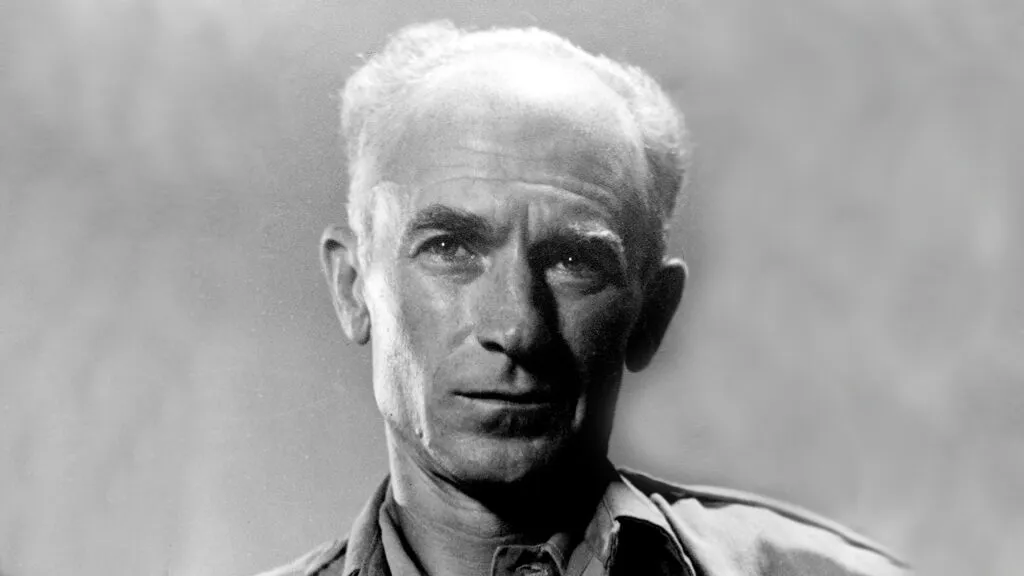

On my way back, a grizzled guy ran up to me. He was wiry and short, wearing oversized fatigues and a helmet that dwarfed him. He carried no gun. All in all he looked a little looney to me.

“Hey, Tex.” he said. “I hear you’re a cowboy. Can I ask you a few questions?”

Questions? I looked for officer’s stripes. None. So I said, “Got no time for questions, mister. My men are thirsty.”

I left the man behind and got water to my squad. By now a smoky dusk had fallen and the artillery had let up. As our company set up defenses for the night a fellow infantryman said to me, “Did you hear that Ernie Pyle is here?”

“Who’s Ernie Pyle?” I asked.

“The famous war correspondent.”

“Never heard of him.”

“Well, you ought to. For us infantrymen he’s the best friend we’ve got”

With nightfall the German 88s let loose again, and our guns answered back. I took cover in a German-dug foxhole, crouching with my rifle. And out of the darkness I saw the grizzled guy running, this time carrying a box and a notebook. He jumped right into my foxhole.

“Hello again, Tex.” he said. “I’m Ernie Pyle, Got time for questions now?”

“I guess so. But it’s awful dangerous out here, mister.”

“Don’t worry about me, you should’ve seen Sicily,” he said gruffly. “So where’s your horse, the one you were on this afternoon?”

“On a boat for England if he’s got any sense.”

“Pretty wild here.”

“You bet it is.”

A tree stood above us, stripped bare by shellfire. Between rounds Ernie Pyle asked me about civilian life. I told about rodeo riding and wrangling. He wanted more specifics. I told about driving cattle down in winter storms. Hunting elk in the hills. Ernie jotted down my answers. He got to asking me about the war.

“I’m fighting hard, Mr. Pyle. but it’s hell out here. At times, when the big guns get whaling away, when snipers start poppin’ from the hedges, I just want to fold my tent.”

“You’re not alone. Tex. I’ve met guys all along the front who feel that way.”

“That may be true. but it ain’t very comforting.”

“But a lot of those boys fight off that pitiful feeling,” Ernie said. “When they get down, they think of home, but they don’t pine for comforts and safety and all that. They think of the trials they’ve endured … the values that’ve held them up. Take a West Virginia boy I saw yesterday, an infantryman like you. He always carries a little chunk of coal in his pocket. He’s a miner, from a family that’s always mined, and when he gets battle depression he reaches into his pocket and clenches that bit of coal. Then he says to himself, ‘If I can take the mines, I can take this.’

“War or no war, Tex, struggles never let up. You keep the good ones in mind. You’re a cowboy. Just think of what you’ve lived through.”

I mulled Ernie’s words. Ever since boyhood, growing up in a shack on the Colorado plain, I’d been tested by endless chores, bitter winters, and, later on, by the ornery animals and trail bosses of cowboy life. What got me through? My mother’s guiding hand, mainly. She’d planted faith and decent habits in me. Always said that you’d know strength and goodness as long as you heed God’s will. And now Ernie had taken my ma’s wisdom and turned it into a soldier’s lesson: To find strength in battle you take hold of strength you’ve known at home … and of the faith that underlies it.

Ernie and I kept talking. I wanted to pry more wisdom out of him, but just then a German shell landed nearly in our laps. Our bones rattled and a ton of dirt showered onto us. We struggled out of the foxhole. Ernie had lost his helmet. As we ran for better cover, he said. “Maybe I’ll see you again, Tex. And, hey, my typewriter is buried in that hole. If you ever dig it out, it’s yours.”

That’s the last time I saw Ernie. The next day I did dig out his field typewriter, but he’d left our area. I entrusted the typewriter to a guy in Ordnance and went back to battle.

I can’t say Ernie’s advice made me invincible. In fact, a week later I was badly wounded at St. Lô and was sent to England for six months. When I returned to the front, though, during the infamous Battle of the Bulge, I kept my nerves by keeping in mind those times when I’d struggled through some bad times. I’d think of a rugged ride I’d weathered, a bull I’d stayed on. I lasted the war and won two bronze stars for bravery in battle.

As you probably know, Ernie Pyle was killed on April 18, 1945, by Japanese gunfire in the Okinawa campaign. The end of the war was near and I thank God Ernie was around for most of the fight. He made us fighting men known to the folks back home, and he made us known to ourselves.

Gain strength by keeping in mind the strong things you’ve done—and where you got the strength in the first place. Ernie’s lesson is 41 years old for me, but I still live by it.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.