Howard Thurman’s life helped change history. But few people know of him.

Some say the signs were there from the beginning. From the very moment Thurman was born, on November 18, 1899, in West Palm Beach, Florida. He came into the world with a caul—the membrane of the amniotic sac—covering his face. Folklore held that this rare occurrence was both a blessing and a curse, granting the ability to foretell the future but at the cost of living with a heavy heart. His grandmother, who had been born into slavery, was an experienced midwife. She acted quickly, piercing the baby’s earlobes while removing the membrane. The only way, it was thought, to break the curse.

By the time Thurman was old enough to inquire about the holes in his ears, he was already having visions. He’d see a face and know that something was about to happen to that person. He felt a deep connection to the natural world. While staring out at the ocean or taking walks in the woods, he’d feel an overwhelming sensation, as if gaining a depth of understanding about the universe he was incapable of knowing on his own. It was here, surrounded by nature, that he felt God’s presence.

He felt it too in the peculiar encounters with strangers that graced his life. As a teenager, Thurman felt called to be a minister. In Daytona Beach, where his family lived, there were no schools for African-Americans beyond the seventh grade. The closest black high school was in Jacksonville, a hundred miles away. Thurman applied and was accepted. He’d be able to live with a cousin and work pressing clothes to pay tuition.

So at 13, Thurman said goodbye to his family. A friend dropped him off at the train station. For the fare, his mother had borrowed money from an insurance policy. Thurman went to the ticket window with his battered trunk. It had no lock, no handles and was held together by rope.

That’s when he learned the railroad required all checked trunks to have handles. The only way to get his things to Jacksonville would be to pay extra and have the trunk shipped by “railroad express.” But that was money he didn’t have. Thurman sat on the steps of the station, head bent, tears streaming down his cheeks.

Then he saw them.

“I opened my eyes and saw before me a large pair of work shoes,” Thurman would recall years later in his autobiography. His gaze traveled upward to find a Black man dressed in overalls and a denim cap.

“Boy, what are you crying about?” the man said. Thurman related the trouble he was in.

“If you’re trying to get out of this town to get an education, the least I can do is to help you,” the man said. “Come with me.” The man paid for the trunk to be shipped and handed Thurman the receipt. Without saying another word, he turned and disappeared down the train tracks.

He was always grateful for his mysterious benefactor. He began to think of everyone as being connected, in some unseen fashion, like atoms bouncing off each other, setting off a series of chain reactions, not at all randomly, but part of a plan, a master blueprint.

Twenty years later, Thurman stood on the other side of the world, gazing into Afghanistan across the Khyber Pass, the fabled mountain trade route. The last place he could have ever imagined life taking him that day at the train station in Jacksonville. It was 1936, and Thurman was an esteemed professor of religion at Howard University. He’d been invited to India, Ceylon and Burma on a months-long trip as part of an African-American delegation representing the YMCA and YWCA—a “Pilgrimage of Friendship.” Thurman had resisted going. He didn’t think he was the right person for the job, even if it meant a chance to meet Mahatma Gandhi.

Now his eyes took in the seemingly endless path before him, twisting its way through the mountains. A place explorers and traders had ventured for hundreds of years. His mind suddenly became transfixed, shutting out everything around him until there was absolute stillness. Thoughts invaded his consciousness. Thoughts he knew were not his. He saw, in this illuminated state, a world not divided by nations’ borders, by money or power, race or religion. But a world as one. All were God’s children. Standing at the Khyber Pass, Thurman felt a deep call to action.

Weeks later, Thurman would at last meet Gandhi. But it was Thurman’s vision at the Khyber Pass that really stayed with him. When he returned home from his trip, he set in motion a plan to form his own congregation, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. A place where people of all races would feel welcomed. He hoped it would spark a movement across the country. But he never attracted much of a following.

At Howard University, his sermons had drawn hundreds of worshipers. In San Francisco, Thurman was sometimes preaching to just 50 people. All his life, he’d felt God leading him. Had he somehow misunderstood God’s purpose for his life? Was his epiphany at the Khyber Pass an illusion?

In 1949, Thurman wrote Jesus and the Disinherited, calling for people to see beyond race. The book wasn’t a huge seller. But among the few who took notice was a 20-year-old divinity student from Georgia. A man who’d go on to lead a bus boycott protesting the arrest of Rosa Parks. He was a virtual unknown at the time, called on to address an overflow crowd at the Holt Street Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. There was no time to write a speech. He’d have to speak from his heart.

“We the disinherited of this land, we who have been oppressed so long are tired of going through the long night of captivity,” the young man said. “And now we are reaching out for the daybreak of freedom and justice and equality.”

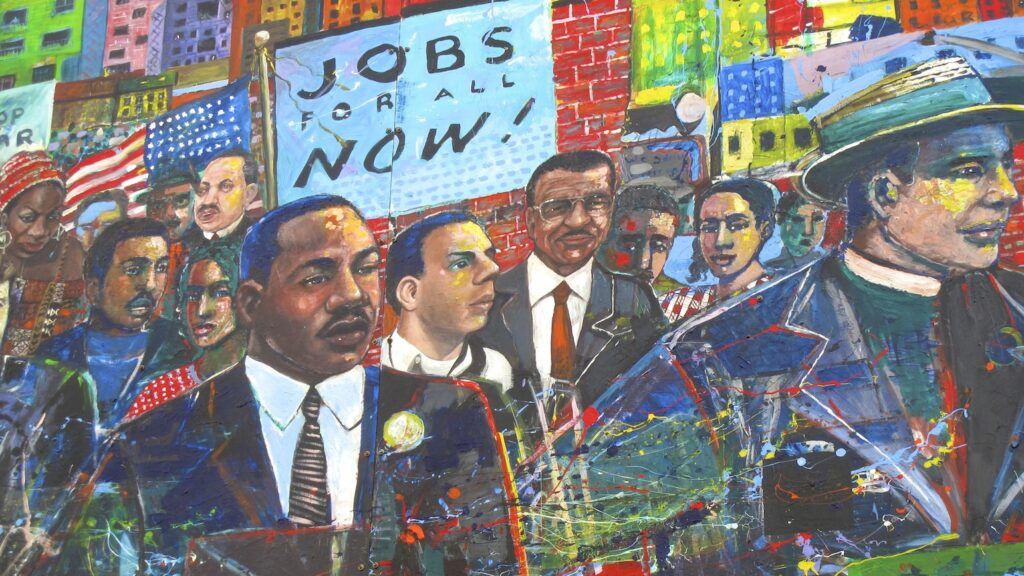

It could have been Thurman just as easily saying those words as Martin Luther King, Jr. Thurman went on to become a trusted advisor of the civil rights leader. In fact, King carried Thurman’s book with him wherever he went.

Thurman was surely honored but not surprised. To his way of thinking, the connection had been there from the day he was born.