This interview is part of our What Our Faith Calls Us To series.

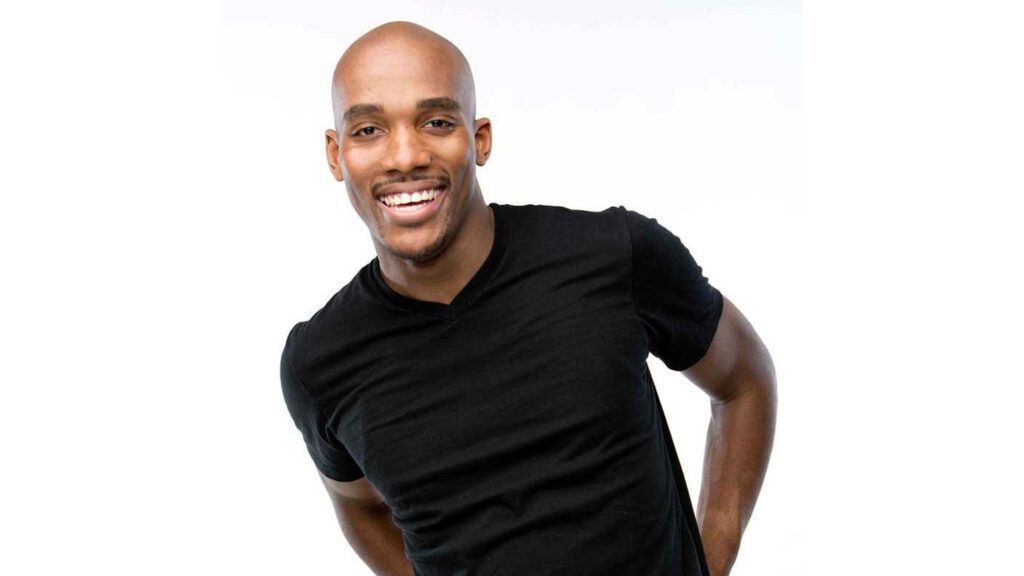

Sam Collier, a pastor, speaker, and author, has discussed race relations with some of the world’s most influential leaders, including Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg. He has counseled the family of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and works with other faith-based leaders to get them thinking and talking about race. In his new book A Greater Story, Sam reflects on how his incredible life story—he and his twin sister were adopted from foster care and were later reunited with their birth mother on The Steve Harvey Show—shaped his faith and unique outlook on racial reconciliation. Collier, who lives in Atlanta, Georgia, with his wife and daughter, suggests ways we can all use our faith in the fight against racism.

GP: What was it like growing up the South?

SC: I grew up in Atlanta, the birthplace of the Civil Rights movement and a Black mecca in the U.S. My father owned a barber shop right across the street from where Martin Luther King, Jr. is buried. I remember walking down the street and seeing murals of great Black leaders like John Lewis. I even have a picture of myself sitting on John Lewis’ lap when I was six after my dad cut his hair.

For me, racism is like the weather. It’s a normal part of your routine, you build your wardrobe around it. You adapt to this environment. But when I would experience opposition, I would look up to those Black leaders. I would see that mural of John Lewis and know that he did it, so I could do it.

GP: What are you currently doing in your community to bridge the gap between races?

SC: I consult with a lot of faith-based leaders on the issue of race and diversity. I start conversations and try to be a voice of reason during this time of civil unrest. I’m also working with large predominately white churches to help them staff in a more diverse way and create a culture of diversity.

I’m working with a lot of organizations who are trying to respond to the Black Lives Matter movement. Organizations are recognizing there is a problem. They realize they haven’t taken the conversation seriously enough; I work to help with that.

GP: What inspired you to devote your life to this work?

SC: This is something I stumbled into. I grew up in all Black neighborhoods and environments. I didn’t have my first experience with a [predominately] white environment until I was 21 and a close friend invited me to join a white ministry. Growing up in a Black church and moving into that white space….it took me four years to become relevant there.

In ministry, everyone has different problems; you have to understand everyone’s plights. Being in that space, people started asking me, ‘How did you do this? How did you leave a Black church and move into a white ministry? That threw me into a lot of conversations about race. From there, with my unique perspective, it started opening doors for me. Doors to speaking about race. To consult. To have unique moments and opportunities and conversations. People asked for my perspective. I found that I had a specific disposition for it that allowed for me to succeed in this.

GP: You’ve had conversations with some of America’s most influential leaders regarding race relations. What are some of the biggest lessons you wanted to teach?

SC: The main thing I have seen is a lack of understanding, a lack of exposure, and a lack of relationship.

We’re constantly asking, why are we still facing this issue? There are good people on both sides. But the narrative for Black people has become that white people know— and don’t care. At the same time, white people don’t actually know our plight at the deepest level. That basic premise, while very simple, leads to massive tension and lack of systemic change. But when you get Black people to understand that the majority of whites don’t actually understand the struggles, and you get white people to believe that they didn’t know the whole story, you can change the conversation.

GP: You have provided counsel to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s family. What did you learn from this?

SC: They mentored me for four years; I still have holidays with them. I’ve had the opportunity to open doors for them in white spaces. Being able to bridge the gap there has taught me the power of proximity. The closer we get to something, the clearer it becomes. It is easier to make assumptions from afar, but our assumptions are flawed. When we get close to something, we can see what it is and how to approach.

GP: What do you feel is the connection between faith and racial justice?

SC: I think of the Parable of the Good Samaratin, which underscores the great commandment: love they neighbor as yourself. The man in the story asks Jesus, “Who is my neighbor?” He is trying to find a loophole because, historically, Samaritans and Jewish people were not supposed to associate with each other. But loving your neighbor, this requires us to put down what our culture says we should do. There is a wrong that needs to be made right. It always leads me back to this question: What does love require of me?

GP: What can people of faith do in their community to help support and educate each other?

SC: I think there’s a lot that can be done. First, we need to start at the foundation. Obviously, there’s systemic change that needs to happen on the economic and legal levels. But all of that starts by asking that question: what does love require of me?

I have found that for people of faith, we consistently put the cart before the horse. We want those in positions of power to change things. It’s the reason we keep hitting a brick wall. The only way to bring those in power into understanding is through relationships.

The heart of the Civil Rights movement was relationships. People saw the protesting, heard the songs, heard the speeches, but what is often left out are the conversations. It is during those one-on-one meetings that change happens. The protests, the songs, the social media posts, they are all important, but they need to lead us to that conversation, that relationship, that reaching down and picking up our neighbor. Otherwise we will keep doing the same thing.

We need to start those conversations. To actually schedule times to do them. There’s are fantastic groups, such as Be the Bridge, that offer structure and discussion guides for having these conversations.

If the pastors, the people in power, get every person in their church to care about this issue and to live their life with people different than them, they could easily change their community. Every leader has a sphere of influence that can create systemic change. Every person has influence that can create cultural change. What I have seen from my experience, is that when people get in real relationship with people who are different from them, they automatically begin to carry their burdens. Then, change is inevitable.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.