I have a confession to make: I didn’t come to New York to be a writer and editor. I came here to be a professional singer. I’d sung a lot in college, in the chapel choir, in glee club, in an a capella men’s group and in musicals. I figured I was ready to take on the Big Apple.

I was accepted at the Manhattan School of Music, snagged a paid gig in a church choir and found a couch to sleep on in a rambling Upper West Side apartment.

Two of my roommates were actor/singers. They were actually in Broadway shows at the time. They would come home from the theater and start singing arias at midnight.

“Rick, check out my high C.” “How do you think my French accent is on this song?” “Do you think this piece will work for my audition tomorrow?”

I loved all of it, even if I found it intimidating. Would I be able to perform in a Broadway show or sing opera and concerts, the way they did? The city was full of talented up-and-comers.

There was good singing everywhere… clubs, Broadway, Lincoln Center, even in the parks and on the subway. But we all knew the very best place to be heard, the venue that signaled you had really made it: Carnegie Hall.

I remember taking a girl to a sold-out recital there when the only seats left were tucked onstage behind the singer.

For most of the concert we could only see his back—occasionally he’d turn and bow to us—but we could see the hall as he saw it: seemingly limitless rows of seats rising all the way to the upper balconies, where the people looked like peapods.

“Can you imagine singing here?” my date whispered.

Funny thing was, I could. I mean, it would be scary, but wouldn’t it be amazing? Just to feel your voice disappear into the vastness of that celebrated hall, the famous acoustics of the place amplifying your singing so you could be heard by the peapods all the way in the back of the upper balconies.

Maybe, I said to myself, someday.

“How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” the old joke goes. Answer: “Practice, practice, practice.” Well, I practiced hard.

I took dance lessons and acting lessons along with my voice lessons so I could market myself as an actor/singer who could “move well.” I had professional photos taken and mass-mailed my 8-by-10 glossies and résumé to casting directors and agents.

I auditioned all over town, waiting at cattle calls to sing “a few measures” before being told “Thank you,” which usually meant “No thanks.”

I did musicals in church basements, sang South Pacific and West Side Story in summer stock, was a spear carrier in Shakespeare, got tenor gigs in various choruses and did so many performances of children’s theater that I could recite lines in my sleep.

And yet my dream did not come without doubt. I asked myself and God, Is this really what I’m meant to do? Not that I wasn’t grateful to be employed in such an incredibly competitive business, but was it really me?

If God gave me this gift—and singing felt like a God-given gift—was this how I was supposed to use it?

I liked the people I worked with, but to tell the truth, I didn’t really like the work.

I didn’t like traveling all the time. Didn’t like bonding with a group of singers and actors for several intense weeks only to go our separate ways after the show was done. Didn’t like not knowing where the next job was coming from. Didn’t like getting nervous before a show.

More important, I had fallen in love with the woman I’d taken on that date to Carnegie Hall, and if we were to be married and have children someday, was this the life I wanted as a husband and a father? The life of a vagabond tenor?

We got married and had so many of our musical friends perform during the ceremony, hitting their high C’s, that it sounded like a concert. By then I had relaunched myself as a writer/editor, almost as precarious an existence as that of an actor/singer, but not quite.

“Practice, practice, practice” is good advice for writers too, and gradually I made a career for myself, landing on staff at the magazine you are now reading, where I have been very happy, happier than I would ever have been as a professional tenor.

Besides, I still found places to sing for the sheer amateur joy of it. Sundays with our church choir, concerts here and there and an excellent Gilbert and Sullivan group, the Blue Hill Troupe, where I often was cast as the lead.

Performing a few nights a year for friends and family was better than a life on the stage. Broadway didn’t miss me.

Then, a dozen years ago, the Blue Hill Troupe was asked to give a concert with the New York Pops orchestra. Guess where? Carnegie Hall. It would be a night to remember, singing in the chorus, looking out over that famous hall.

Then the director called. “We want a couple of our soloists to perform. I want you and Joanne to do the love duet from Pinafore. Okay?”

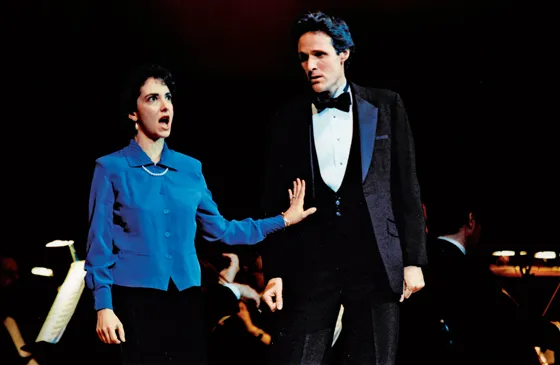

“Sure,” I blithely said. I hung up and pulled out the score. My friend Joanne Lessner and I would have to stand up in front of the orchestra next to the conductor and sing 42 measures all by ourselves onstage at Carnegie Hall. How thrilling! How absolutely terrifying!

We practiced, practiced, practiced. On our own, together, with a pianist and on the afternoon of the actual performance with the full orchestra.

The red seats were empty, but I did steal a glance up and could picture someone looking down and seeing how very small I was on the vast, fabled stage where the greatest singers on earth had performed.

“God,” I muttered, “this might have been a dream of mine long ago, but I feel completely inadequate now. Why on earth did you let me say yes?”

“You sounded great up there,” my fellow tenors said. They had to be lying. Couldn’t they see me balling my hands into fists to keep them from shaking? Couldn’t they tell that that vibrato was coming from sheer nerves? That I was squeezing out every note?

If I could only back out of the whole thing now… but my name was in the program. People were depending on me. I couldn’t disappoint them.

My long-lost dream of performing at Carnegie Hall was coming true, whether I liked it or not.

I prayed on the subway train that evening, wearing my tux, heading to Fifty-seventh Street. Please, God, just don’t let me mess up. That’s all I ask. I kept picturing the conductor waving his baton at me and nothing coming out of my mouth.

Backstage the conductor gave the troupe a pep talk: “Have fun out there.” We patted each other on the back and then filed out onstage.

Joanne’s and my duet wouldn’t come until halfway through the program. That meant I had to sing a half dozen other pieces with the chorus, marking the minutes to my doom.

Finally it was our turn. our cue came and Joanne and I walked forward. The conductor lowered his baton. The orchestra began. And we sang, the music rising to the back of the hall.

I don’t know how it happened. I didn’t flub a lyric, didn’t miss a note, didn’t run out of breath, didn’t trip over my feet. Didn’t mess up. The nerves gave way to calm and then the calm gave way to joy, the joy of using a God-given gift. God wouldn’t have put me there if I couldn’t do it.

We finished and bowed. The audience applauded. The 42 measures were over. We walked back to join the group for the rest of the concert.

“Flawless… awesome,” my friends in the tenor section congratulated me under their breath. You did it, I thought with glee. You really did it. You’ve sung in Carnegie Hall! I was in awe.

But at the same time I told myself, You don’t ever have to do this again. Once for a lark, once for the challenge, once to say that you’ve done a thing you dreamed about. Once to know that you have made the right choices in life and have used your gifts to the best of your ability.

Once in a lifetime was enough. More than enough.

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith