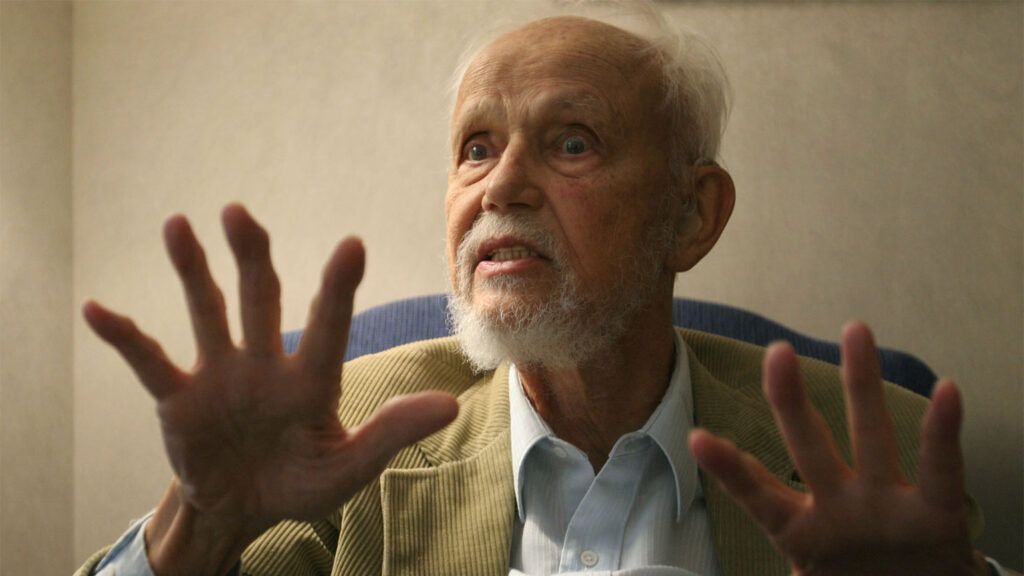

Religious studies scholar Huston Smith passed away on December 30, 2016. In tribute to the author of The World’s Religions, we share with you this story he wrote for Guideposts in August 2002.

My parents were Methodist missionaries in Changshu, a rural town some 70 miles northwest of Shanghai. For my first 16 years, Changshu made up my whole world. Life had changed very little there over the centuries, and that slow pace brought a capacity to experience the mysteries of life and death.

Wesley, Jr., the first of my parents’ children, came into the world in August 1914. Infectious disease was rampant in China at that time, and Wesley died in their arms two years later.

Long before I was old enough to grasp the matter intellectually, I sensed that it was my parents’ Christian faith that brought them through the tragedy of losing Wesley, Jr., so soon. After all, they were careful to raise me in the conviction that faith was the single most powerful force in people’s lives. With it, few things were impossible. Without it, life was meaningless.

VISIT OUR ONLINE SHOP FOR BOOKS THAT WILL STRENGTHEN YOUR FAITH

I assumed that I would become a missionary myself. Perhaps I would run the primary school my parents established in our town—the first to admit girls. But at 17 I came to America and entered a small Methodist college in the Midwest.

The town had a population of about 3,000 and a town square surrounded by a dozen or so stores, a gas station and a movie theater. To me it might as well have been Times Square! When my four years of undergraduate study were done, I decided not to return to China but to stay on in America to study philosophy at the graduate level at the University of Chicago.

It was the forties, when traditional religious beliefs were everywhere being called into question. Certain professors even claimed that religion was on a virtual par with fairy tales—an imperfect and obsolete tool for making sense of life’s apparent contradictions. Scientific advancement and breathtaking technology could now explain the world and make life understandable rationally.

Something in my bones told me that this couldn’t be the case. If I’d learned one thing in China, it was that tradition and faith weren’t barriers to truth, but windows through which the great mysteries of life and death could be most clearly grasped and accepted.

Cultures might differ, but underlying them all, like a great sea, was a basic trust—a confidence that ultimately we are loved and that, as the Christian mystic Julian of Norwich said, “All manner of things shall be well.”

By the time I was out of graduate school, I was so convinced of the continuing importance of the role that religious belief plays in people’s lives that I was prepared to devote the rest of my life to arguing for this point of view in the face of modern skepticism and cynicism.

I got married and my wife, Kendra, and I started a family, with Karen, our oldest, arriving in 1944. The next year, I received an advanced degree in philosophy and comparative religion. I became a professor of philosophy of religion, and in 1958 joined the faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

MIT was at the center of the modern scientific worldview. I could not have picked a more exciting—and more challenging—place to teach. But it was through caring for our children with Kendra and watching as they grew into adults that I was most able to make use of the religious values I was arguing for.

Faith is what makes all of our experiences, from our greatest joys to our most terrible pain, comprehensible. I had learned this from my upbringing and my years of teaching, writing and raising a family. Then came the afternoon in 1994, just a few months before my seventy-fifth birthday, when we received a phone call from Karen.

“Mom and Dad,” she said simply, “I’ve got cancer. The doctor says I have four months to live.”

READ MORE: A FORCE BEYOND OUR UNDERSTANDING

We quickly fell into the pattern of driving the 60 miles to Karen’s home each week to spend the day with her. I expected holiday visits to be the hardest. How, without completely breaking down, could I bear to hear “Happy Mother’s Day!” or “Happy Father’s Day!” knowing that it would be the last time I would ever hear those words from Karen.

To my amazement, Karen’s courage and serenity were able to turn all those visits into happy ones. She smiled with complete sincerity when she hugged us good-bye, whether standing with the aid of a cane, sitting in a wheelchair, or, finally, lying in a rented hospital bed.

With faith and the strong support of her family and synagogue—when she married, she had converted to her husband Zhenya’s religion of Conservative Judaism—those four months stretched to seven.

Throughout my life, I have made it a point to stop and pray five times a day—a practice I picked up from my studies of Islam. There wasn’t a single time I prayed in all those months when Karen wasn’t at the center of my prayers.

Karen took her last breath early in the evening of September 20, 1994. Karen loved the sea, and her family, gathered around her bed, heard her last words: “I see the sea. I smell the sea. It’s so close.” I couldn’t help thinking that this great sea which she felt to be so close was nothing less than the sea of God’s love, waiting to embrace her after her long struggle.

At the moment of her passing, in accordance with Conservative Jewish tradition, her husband placed a candle at her head and another at her feet. Lying there in the light of those two flames, her face seemed to take on an aura of peace and tranquility. Always beautiful, she now looked beatific.

Throughout the night, we sat around her body taking turns reading the Kaddish, the traditional Hebrew lament for the dead. As a scholar, I knew the words well. But I had never felt them as I did then. One by one, family members would slip off for catnaps, and from about four to six in the morning I found myself alone with my daughter.

My emotions swung back and forth in great waves. For a spell I would sob uncontrollably. Then, suddenly, the tears would stop and I would find myself in a state of utter calm, peaceful in the knowledge that God gives us life out of his infinite love, and that we return to him in death.

At those times I felt certain that Karen was with me. Not simply her body, and not simply the memory of her in life—but Karen herself. She was with me and also safe in God’s hands.

I found myself thinking back to the terrible loss my own parents had suffered in China almost a century ago, when my brother died after only two short years. What had pulled them through? The truth of faith, and the strength that comes from it.

I had devoted my entire life to studying and arguing for the absolute centrality of these things in human life. Beyond words, beyond rational thought, and beyond even those darkest moments of confusion and despair that come to everyone, God is with us.

On that night of my daughter’s death, I understood—not just in my head but deep in my heart—how true that really is. Faith is believing what you do not see, and the reward of faith is seeing what you believe.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.