Friday. My flight’s overbooked. And there’s a ruckus at the gate. I’m heading to Des Moines, Iowa, to meet Poet Laureate Ted Kooser at the Des Moines National Poetry Festival, but poetry is far from my mind. I’m anxious.

Why has travel become so stressful? Finally, we board. I settle in and go over my notes.

I’ve admired Ted Kooser’s work for ages. In school I copied his poem “The Red Wing Church” onto a sheet of loose-leaf paper and tucked it into my backpack like a good-luck charm. It’s about an old dilapidated church—no steeple, no congregation—transformed into:

…Homer Johnson’s barn, but it’s still a church,

with clumps of tiger lilies in the grass…

That sense of sacredness remains. It’s all around, in fact. But lately I’ve just been too busy to notice.

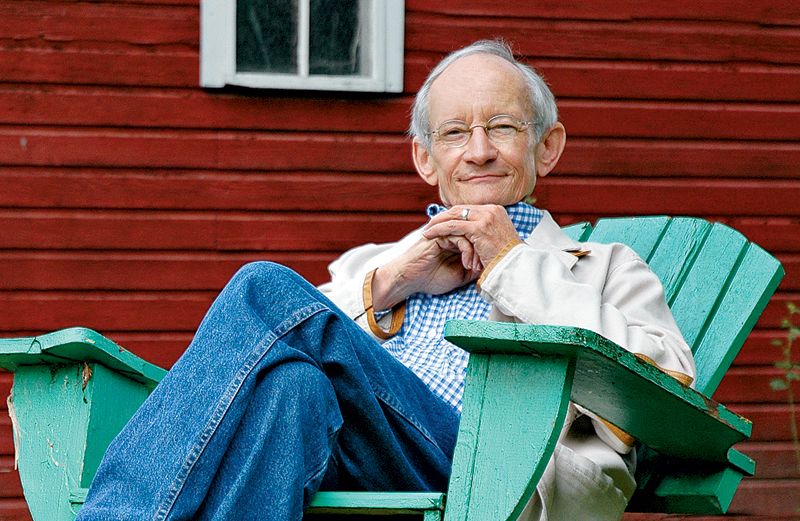

“Rosie from Guideposts,” Ted greets me the next day at the Hotel Fort Des Moines, his voice warm and assured. Now 66, Ted’s appointment as poet laureate was recently renewed by Librarian of Congress James H. Billington, and Ted won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for poetry.

Still, I discover that Ted Kooser is a regular guy. Who happens to be remarkable.

“They put me in ‘The Presidential Suite,’” Ted says, tickled. “It’s bigger than the house I grew up in!” That was in Ames. Ted has lived in Nebraska for decades, but he was in Ames last night, reading at Iowa State, his alma mater.

He pours us each a glass of water and eases into an armchair. “In Ames I visited the church I attended as a boy and spent some time there,” he says wistfully.

“There was an old man, Seaman Knapp, with a collection of bells. At Christmas he always did a bell-ringing in front of the church, running up and down this long table. It’s so sweet in my memory, and he’s been gone fifty years.”

Ted pays close attention to people, places. But he knows it isn’t always easy.

“You drive home from work, find yourself in the garage and can’t remember a thing that’s happened between when you left and when you arrived,” Ted says. “To really participate in life we have to figure out ways of being aware of what’s around us.”

Sure, I think. But how do you do that with a busy life, work, family? “The poet Linda Gregg has her students notice six things a day. Lots of days I don’t notice six things. I’m not always successful,” Ted admits. “But I like paying attention to ordinary things.”

Six things. I make a note. Maybe I’ll try that.

Like the great American poet Wallace Stevens, Ted started out in insurance. His career lasted more than three decades. He rose daily at 4:30 A.M. to write before heading to work. Sometimes poetry and business intersected.

“In the late sixties Bankers Life Nebraska hired an artist to take photos throughout the building, things we passed every day. He gave a slide show and built a production out of the beauty of these ordinary things,” Ted says.

“Poems are like that. They say, ‘Here’s something you may not have looked at. I’m going to show it to you in a way that will make you notice.’”

I ask how poetry took hold in him. “I had an ordinary family, lived in an ordinary town. I wanted to be different. Mysterious. The arts were a way to be different. So I painted and wrote poems.”

Soon his “ordinary family” and “ordinary town” became the subjects of his poetry. Revealing their magic came with maturity.

It troubles Ted when people feel that poetry isn’t for them, that it takes a special skill or degree to enjoy it. His mission is to bring new readers to poetry, to reach regular people in small towns—people like him.

Poetry is a democratic pleasure. The reader brings as much to the page as the author. Nothing pleases Ted more than helping people understand that.

Recently he heard from a new reader. Poetry never interested her, but she’d heard Ted’s poems on public radio. They resonated with her experience of rural life.

“That’s who I want to read poems. Oftentimes a man will come up at the end of a reading and say, ‘I’ve never been to a poetry reading before. My wife dragged me here. But I liked it. I think I’ll read some poems.’”

Ted frets if a line of his poetry is too difficult. Clarity and accessibility are his cornerstones. In his insurance days he’d run poems by his secretary. “I’d say, ‘Does this make sense to you?’ and she’d say, ‘No.’ I’d go home and work on it until it did.”

We’ve talked for more than an hour when Ted excuses himself to get more water. “Dry mouth,” he explains, a lasting effect of the treatment he underwent for oral cancer.

He returns and I ask about that. “June 1998 I went to the dentist. I had a sore spot on my tongue. The dentist referred me for a biopsy right away.”

He was diagnosed with stage 4A cancer. “My surgeon, Dr. Bill, said a marvelous thing: ‘Radiation is gonna be hard. But you are about to enter one of life’s great affirmative experiences.’”

I lean closer. “Did you believe him?”

“I wasn’t in a position to speculate!”

Following his treatment, Ted took walks to regain his strength. Each time he’d bring something home to write about. “Here was a way to take disorder and anxiety, compress them into something small and orderly and take assurance from that.”

Ted was changing, and so were his poems. Now he says, “There’s a real spirit of celebration. I tend to be quite easily moved. More so, having survived cancer.

“I saw people in waiting rooms who were almost beatific in their love of life, their desire to live. There was a tremendous amount of grace in those waiting rooms.” One poem, “At the Cancer Clinic,” records that situation, and ends:

|

…Grace

fills the clean mold of this moment

and all the shuffling magazines grow still.

|

Dr. Bill framed a copy of “At the Cancer Clinic” and hung it in the hospital. In hopes, surely, that those who see it will draw strength from it and, perhaps, grace too. I share with Ted my simple belief that poetry just makes life better.

“It makes life bigger too. Suddenly an artichoke is more than a thing,” he explains. “Joe Hutchinson has a one-line poem, ‘Artichoke,’ that says: ‘O heart weighed down by so many wings.’

“You get that poem in your head and go to the grocery. That crate of artichokes will never look the same. There’s something special about it.”

That night the Hoyt Sherman Place Theater is packed with people who have come to hear Ted and three other poets read. I scan the crowd and can’t help thinking, Are there men here, grudgingly accompanying their wives, who will leave full of wonder with a new way of seeing?

Sunday. I’m flying home. Try to notice six things. Plump beads of condensation on the window. The earrings—silver filigree set with smoky blue stones—on the woman beside me. A crying toddler, with a shock of yellow curls. That’s three.

Ted was right; it’s hard to pay attention. But I feel its effects instantly. Something much like grace. There’s something special about the window. The earrings. The child. They’re bigger. And I feel connected to all of them. For that powerful feeling, that sense of sacredness, I can never be too busy.

Download your FREE ebook, Rediscover the Power of Positive Thinking, with Norman Vincent Peale