As a meteorologist on TV, I’ve covered every natural disaster from Katrina on. Hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, wildfires—I’ve reported on them all, and one thing I’ve seen firsthand is how people rebound, no matter the devastation. They take stock, draw on their faith, rebuild and grow because they’ve faced the worst. Often they are the first people to reach out and help when others are suffering.

In my own life, I’ve struggled with a different sort of natural disaster—devastating bouts of depression. The first struck when I was 22, a recent college grad looking for a job in television meteorology. I know now that transitions can be a trigger for major depression. Back then I couldn’t understand why I felt life wasn’t worth living. As if I were a prisoner in a strange dark room without even a hint of light.

I’m a people pleaser, and it was as if I had to please even the therapists. I’d tell them what I thought they wanted to hear. I’m sure it looked like I was a big success as a broadcaster, going straight from college to one job after another, moving to bigger markets, from Grand Rapids to Chicago and now New York. ABC News had just hired me to be the weekend meteorologist on Good Morning America. It was all I’d dreamed of and prayed for, all that I’d worked so hard to achieve. Yet I felt empty inside.

Worse than that, I could feel myself plunging into that dark room I’d tried so hard to avoid. It had happened before. Things would be going well, and then the darkness would descend like a fast-rolling fog. I’d find myself trapped in a small, cold place with the blinds all the way down.

This time it hit me in a hotel room in Washington, D.C., where I had a meeting, when I was far from my family and friends in Michigan. I was in deep trouble, and I didn’t want to run away from it, not this time. There was too much at stake.

I called my mom back in Michigan and my cousin and, with their help, came up with a plan. I would check into a mental health hospital in New York for a weeklong, inpatient therapy program before I started my job at Good Morning America. I’d confront this monster once and for all.

Of course, the minute I checked in, I wanted to check myself out. I don’t belong here, I told myself. The other patients seemed really sick compared with me. They had serious mental illnesses, not my garden-variety depression. Some of these people, like my roommate, could barely speak. I wanted her to like me (I wanted everyone to like me), and she just ignored me, didn’t even say a word.

Then I had my first one-on-one session with my therapist, Dr. Wilson. He was clinical, matter-of-fact, not trying to be my parent or best friend. He wanted to get me out of this place, which I wanted too, and for the first time someone helped me connect the dots.

What was it about me that got me sucked into such emotional turmoil? Why did I feel that when anyone was angry or frustrated or sad, it was my fault and I needed to fix it? Why did I always end up going out with the wrong man while running away from men who weren’t natural disasters themselves? Therapists always make you talk about your childhood, and with Dr. Wilson I thought, Oh, here we go again. But he pushed me to untangle the feelings and needs buried deep inside me, and I came to a profound understanding I’d never had before.

My father and mother are wonderful people, and I’ve always felt loved by them, but their marriage didn’t work out. They got divorced when my brother and I were young, and both remarried. He and I spent most of our childhood bouncing from one household to the other with stepparents and half brothers and sisters added to the mix—no wonder I felt compelled to change apartments four times in the five years I lived in Chicago. Chaos felt normal.

The one source of stability was my father’s mother, Hilda Zuidgeest. My Oma (Dutch for “grandmother”). She and my grandfather had emigrated from Holland in the 1950s, after enduring the brutal Nazi occupation during WWII. What she suffered was horrendous, much of which she never talked about, yet she and my grandfather had come through the experience somehow stronger (like I said, I’ve seen this time and again with people who have suffered terrible loss).

She had a thick accent and a great sense of humor. “If you’re not Dutch, you’re not much,” she’d say with a smile. We went to her house for Sunday dinner. She would say grace, thanking God for the good food and our family. She usually put in a joke that made us chuckle, then we would eat. Roast chicken, mashed potatoes, cauliflower with cheese, salad, crepes, an apple pie that she got at the diner where she bused tables, all served on blue-and-white Dutch plates in her dining room with blue-and-white curtains, the cuckoo clock on the wall singing out the hours.

She was tall, strong, with curly white hair and a taste for craft-show sweatshirts with colorful appliqués. Most of all she was honest—intensely honest—with others, with herself, with me.

In my early twenties, I was engaged to a guy I knew I shouldn’t marry. I tried to stop the wedding once. I’d put all the stamped and addressed invitations in the mail, only to go back to the mailbox hours later and plead with the postman to let me have them back—God bless him, he did. Then my fiancé urged me to reconsider. I agreed to go ahead with the wedding, mostly because I didn’t want to hurt his feelings.

Three weeks before the wedding, Oma and I went cherry picking. We were going to use the cherries to make jam as favors for a wedding that I knew shouldn’t happen.

After an hour, Oma grabbed my basket with her weathered hands. “Let’s rest for a moment,” she said. We paused, then she looked at me, her blue eyes piercing. “If you don’t want to get married, you don’t have to,” she said.

Long past when any guests could fully refund their airfare or the bridesmaids could cancel their dresses or we could get the caterer’s deposit back, Oma spoke the truth. And that allowed me to recognize it. As much pain as it would cause others—I still can’t bear to recount the tearful conversation I had with my soon-to-be ex-fiancé—it was more important to be honest.

This was the message that Dr. Wilson tried to convey to me in the intense sessions that we had. Finally I understood. I would never get myself out of that dark, gloomy room of depression if I kept running away from any possible conflict, if I didn’t separate other people’s feelings from my own, if I insisted on pleasing others without paying attention to how I felt.

By the time I finished that inpatient hospital stay and started my new job at Good Morning America, I was a different person. There was a lot more work to do, and I met regularly with Dr. Wilson, learning how to look more deeply at my inner life, how to track emotional storms as closely as I did meteorological storms, how to be likable by liking myself first, following the Golden Rule, to love your neighbor as yourself.

Finally when the right man came around, I was ready—okay, I got scared off a couple times because Ben was so easygoing and joyful and loving and not given to chaos of any kind. We married in June 2014. We had our first child, our son Adrian, named for my Dutch grandfather, in December 2015. When he put his cheek against mine for the first time in the delivery room, I felt this deep and instant love.

One thing I want to do for Adrian and his baby brother is re-create those Sunday dinners at Oma’s. Not just the food—although I wish I could make those crepes like Oma did!—but the warmth, the trust, the dependability, the good humor and the gratitude in everything she said, everything she did.

And when someone attacks me on social media, telling me how lame a segment was or how awful my clothes were or how ugly my hair is, I make a point of saying, “I’m sorry that’s how you feel….” I want to let that person know I value their opinion even if I don’t agree with it. And as Dr. Wilson taught me, I don’t absorb all their negativity.

Depression is different for everyone. Some people require more extensive therapy or hospitalization or medication. Some slip into dark places where they are tough to reach. What I appreciate about my journey of depression is that it has made me stronger, more compassionate, more understanding.

That’s what I want to tell anyone who has weathered one of life’s storms. You can get through it and become a better person. Those natural disasters have purpose, and with hard work—emotionally and spiritually—you can find gratitude in each of them. The clouds don’t last forever. They can’t and they won’t. That’s just how the atmosphere—and life—works.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.

|

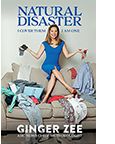

Ginger Zee is the author of Natural |