Growing up in a small town in West Virginia, I’d always dreamed of the adventures I would have when I went out into the world. It was 1963, the spring of my senior year at the University of Pittsburgh, when I saw a movie called Come Fly With Me, about three young stewardesses and their adventures.

One stewardess was always in a predicament of some sort; another was shy, demure and reserved. But it was the third who captured my imagination. She was so elegant, with a serene face and a voice like warm honey.

Who was this woman? I wanted to be like her—young and vibrant, in what felt like the most exciting time in history to be young and vibrant.

I read a review of the movie and learned that the actress who had made such an impression on me was Dolores Hart. One critic deemed her the next Grace Kelly.

Close to my age, she had already gotten a Tony nomination for a performance on Broadway, and had appeared in a range of movies from Where the Boys Are to a co-starring role with Elvis Presley in King Creole.

Dolores Hart—forever linked in my mind to her stewardess character—was everything I wanted to be: attractive, confident, adventurous.

The next week, on my way to class, I noticed a poster in a travel-agency window: Be a Stewardess, Wing Your Way to Adventure. Ever since I’d been a little girl, I’d prayed to discover the right path for my life.

As I saw it, that included travel and adventure, with a marriage and family somewhere along the way. Come Fly With Me made me think a stint as a stewardess was the ideal launching point. I went through a series of interviews with TWA, and was hired.

After college I went off to “hostess training,” a whirlwind combination of flight academy and charm school. Then from my base in San Francisco, I flew all around the country. I tied my scarf the same way Dolores Hart did in the movie, and tried to be as gracious and self-possessed as she was.

It was hard to imagine that just a few years before, I’d been living with my parents in a West Virginia steel town.

One day while waiting for passengers to board, a startling headline on a newspaper caught my eye: Actress Leaves Career to Join Convent. Dolores Hart was abandoning her Hollywood life to become a cloistered nun. Is this a publicity stunt?

I scanned the article but there weren’t any specifics about where she was going, just a quote to the effect that she felt this was where God was leading her. I couldn’t help thinking, Why would an attractive young woman give up a glamorous life to join a convent?

In the meantime, I was ready for a change of my own. While I loved flying—the roaring shudder as the jet lifted off the runway, the sweep of clouds struck golden by slanting rays of sun, the glitter of stars as I stared out the galley window at night—I hadn’t counted on being so jet-lagged and footsore.

After a year I turned in my airline wings.

When I was about 10, I’d put out a neighborhood newspaper from our backyard in West Virginia. In college, I’d majored in writing. I was ready to widen my horizons in journalism. I moved to Manhattan and got a job at the Saturday Evening Post.

Eventually I moved on to Seventeen and McCall’s, my love for my work and for the rhythm and color of city life cradling me as surely as the embrace of a small town. Yes, I was living out my dreams, having a grand adventure. Even in my 40s, when I came to work at Guideposts, I still felt brave and frisky and…young.

Then gradually I noticed it happening. When I walked too far in high heels, my knees hurt. I’d glimpse my reflection in a store window and wonder why that older woman was wearing my clothes.

So much of my identity involved being a young woman. I never anticipated that I’d wake up in the middle of my life and be blindsided by the fact that even members of the sixties’ “Youth Generation” don’t remain young forever.

As I approached 50, I felt disoriented and afraid, even angry. It seemed I’d hit some bumps on “the right path,” and the husband and children that I’d expected to share my life with never materialized.

Nothing had prepared me for aging—not college, not hostess training, not even my years in the working world. Was there really such a thing as growing older gracefully?

Then in 1994 I walked into a crowded ballroom at a writers’ convention and, out of perhaps a thousand people, sat down next to a dark-haired woman who introduced herself as Antoinette Bosco. As we chatted, I felt an unexpected urge to open up to her.

“I’ve been having trouble coping with getting older,” I blurted out. “Sometimes I feel so alone and unsure about the future.”

“There’s a special place I go when I’m feeling like that,” Toni said, “not far from where I live in Connecticut. It’s called the Abbey of Regina Laudis. I always have a better perspective on things after I’ve been there. Come visit and I’ll take you.”

In my mind, I pictured a medieval stone edifice on a fog-shrouded mountaintop.

One August afternoon a few weeks later, Toni met me at the bus in Danbury. We drove through rolling hills and woodlands until we reached an opening in the trees and swung into the abbey’s small parking area.

Instead of the intimidating setting I’d imagined, I saw what seemed to be an old farmhouse with a rustic wooden cross on its roof and a greenhouse as its entryway. A tractor rumbled past, driven by a ruddy-cheeked nun in long skirt and flowing wimple who waved at us merrily.

“The nuns run these three hundred and fifty acres as a farm,” Toni explained as we strolled along.

“Close to forty sisters live here,” Toni went on. “Some came to the abbey after successful careers as lawyers and teachers, one was in the state legislature. They wear full habits and never leave the grounds except for emergencies or special studies.”

She pointed toward outlying buildings. “Over there are a blacksmith shop and kilns to fire the nuns’ pottery. Sister Debbora is a beekeeper; others bake bread, milk the cows, tend the oxen.” She told me the sisters had just built a chapel where they gathered to pray and sing eight times a day.

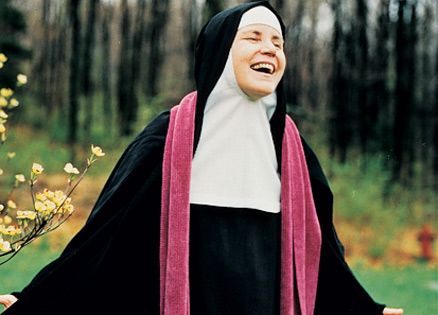

From the far side of a field, a nun appeared and swept down a grassy slope toward us. A wide straw hat with a floppy brim sat on her head over her wimple, sneakers peeked out beneath her long black skirt. Something about her seemed familiar. When she came closer, I caught my breath.

I knew that face framed in an oval of white, but now there was a gentle webbing of lines around her blue eyes and smiling mouth. “Mother Dolores!” Toni said. “This is my friend Mary Ann.”

“Welcome,” Mother Dolores said in that rich, honeyed voice I remembered so well. “How wonderful to have you here.” I sputtered something about being glad to meet her. A gust of wind caught the brim of her hat and she laughed and held it in place.

Like me, she wasn’t a girl anymore. But her expression was luminous, her manner exuded contentment and peace. As the bells rang, calling her to afternoon prayer, she invited me to come back to the abbey again.

Some months passed before I was able to return. When I did, I had a long talk with Mother Dolores through a wooden grill that surprisingly only added to the intimacy of our conversation. I poured out how I’d seen her in the stewardess movie, and at the time felt it was a kind of nudge from the Holy Spirit to set me on my path to adventure.

Mother Dolores laughed. She said that it had been in New York, while publicizing Come Fly With Me, that she had made her final decision to become a postulant and join the nuns at the abbey. She’d started visiting the abbey several years before, while performing on Broadway, and “subconsciously something kept drawing me back.”

I told her how I’d wished to be as glamorous as she was—and how disoriented I’d felt when I was forced to face the reality of getting older.

“Back when I was making movies,” Mother Dolores said, “I looked in the mirror one day and realized that if my sense of worth and fulfillment was based on my looks and youth, it was all short-lived.” She leaned closer. “I sensed inside there was something more—much more. And I was right. Time and age don’t matter.”

As I gazed through the grill into her gentle face, it became clear: True beauty comes not from youth or genes or circumstance, but from a wellspring of inner grace that transcends age and environment.

“Don’t worry,” Mother Dolores said. “Wherever you are on your path of life, however unexpected the twists and turns, God continues to draw you to where you belong.”

We prayed together, then the bells rang and it was time for her to go to vespers. As the shadows lengthened, I climbed the hill to the abbey chapel, where the sun’s slanting rays bathed the sanctuary with amber light.

While the nuns filed in and began to sing, I closed my eyes, filled with a deep feeling of peace. Lifted on the strains of their chanting, I felt older…younger…ageless…safe, an ongoing traveler following God’s path as it continues to unfold. Venite…jubilate…alleluia!

I’d finally discovered what had drawn me to Dolores Hart all those years before. It wasn’t glamour or sophistication, as I’d once thought. The Holy Spirit had been leading me to an inner beauty, the eternal beauty of the soul. A beacon that would light my way through the spiritual adventures ahead.

Download your FREE ebook, Paths to Happiness: 7 Real Life Stories of Personal Growth, Self-Improvement and Positive Change