I was six when I fell in love with Christmas carols, especially American Christmas songs. That year, the nuns in the Philadelphia orphanage where I lived took me to midnight mass on Christmas Eve. The crowded chapel, the altar crèche, the scent of balsam trees—it was intoxicating!

But something else thrilled me even more: the music—soaring, majestic religious carols filled me with peace, joy and hope. It was a feeling, a deep spiritual warmth, I’d never experienced, living as I did, without a family, without a sense of belonging.

That night, I felt part of something—something much bigger than me. Where did such beautiful music come from? The question stayed with me all my life.

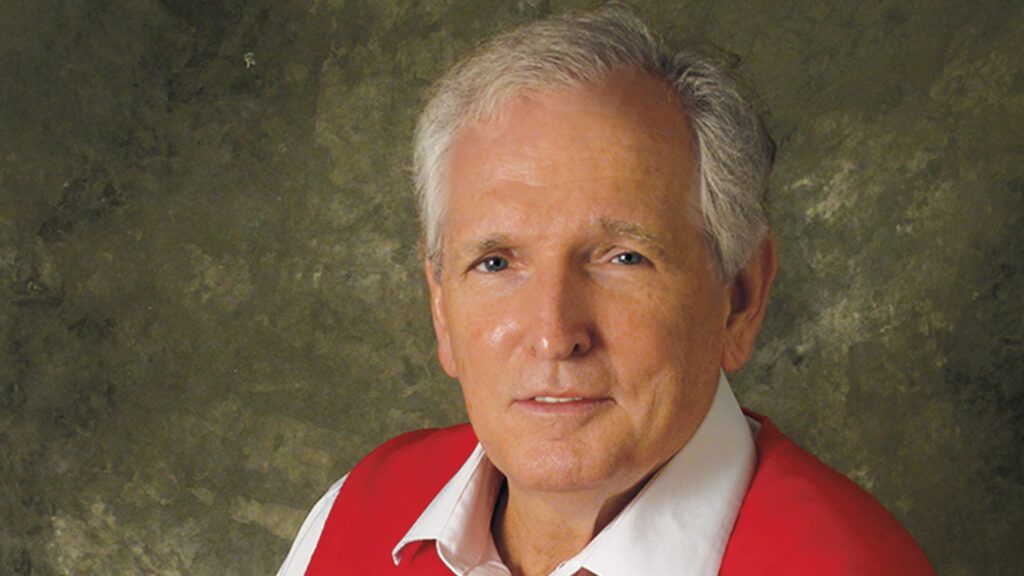

Finally, in my sixties, I needed an answer. I decided to travel 4,000 miles, across seven states in nine days, to find the true stories behind those songs that held such deep meaning for me. I’d collected rare recordings of carols for decades—even compiling them into three richly illustrated book/CD boxed collections.

“I’m going to ask you the biggest favor of my life,” I said to my wife, Renate, one September night after dinner. She knew better than anyone the influence Christmas carols had on me.

“I want to visit the places where American carols originated. I want to get a feeling for what might have inspired their composers.”

I was asking a lot. We both worked—me up at 3:00 A.M. to deliver 230 morning newspapers daily, she as a schoolteacher who often worked till 6:00 P.M. It meant she would have to take over my delivery route, and then head straight to her elementary school. Bless her, she said yes right away.

Savannah, Georgia

Savannah, Georgia

Jingle Bells

I piled a suitcase, a still camera, a video camera and a tape recorder into my sturdy Volvo and headed from my home in North Cape May, New Jersey, to Savannah, Georgia, 13 hours and 760 miles south. My destination was the Unitarian Universalist Church of Savannah, known to just about every Savannan as the Jingle Bells Church.

It was there in 1857, while serving as the church’s musical director and organist, James Pierpont finally copyrighted One Horse Open Sleigh, the Christmas carol now known as Jingle Bells, which he had composed in Medford, Massachusetts, at least seven years earlier.

What a beautiful church, I thought. The stately stone edifice was recently renovated. I tried to imagine Pierpont sitting at the organ, playing his spritely song to the congregants every Christmas Eve.

The man led a complicated life. He moved to the South and fought for the Confederacy, while his brother, John, served as a Union Army chaplain. He died impoverished though his nephew was the great financial titan, J. Pierpont Morgan, said to have more money than the U.S. Treasury.

I would like to have stayed in Savannah a few days more, but the road beckoned. I phoned Renate at the end of the day. “Honey, I’m in heaven,” I said.

St. Helena Island, South Carolina

Mary Had a Baby

“You’re headed to South Carolina tomorrow, right?” she asked.

“Yes, to St. Helena Island,” I said, “just fifty miles north.”

St. Helena Island, one of South Carolina’s sea islands, is home to one of Christmas’s most precious treasures, the carol Mary Had a Baby. Composed there somewhere in the early 19th century, it’s one of the few surviving slave-written carols.

The line that never fails to move me is its last one—“People keep a-comin’ an’ the train done gone.”

There’s no agreement on its meaning, but the interpretation I like best is this one: Trains represented an escape to freedom. And though this particular train had gone, with faith surely they’d find another opportunity.

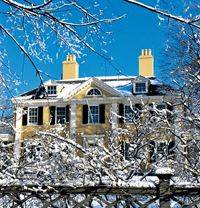

No one knows for sure the plantation where it was written, and today the Coffin Point Plantation is the only one on the island that remains. At one time it occupied 1,120 acres and housed 63 slaves. I found the three-story manor house, white with red-roof shingles, down a quiet back road, near the sea.

Built in 1801, it’s a private home now. No one was there. I backed off the veranda and stood on the ample lawn. I sang the song softly to myself and thought of what the peace of Christmas must have meant to a slave.

Murphy, North Carolina

I Wonder as I Wander

The next morning I drove six and a half hours, from St. Helena Island, to Murphy, North Carolina, in the Great Smoky Mountains.

The Little Drummer Boy

After a full day of travel to All Saints Episcopal Church in Pontiac, Michigan, the source of inspiration for the Alfred Burt family carols, I headed east to Concord, Massachusetts, to visit Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, where composer Katherine K. Davis is buried.

In 1941, Ms. Davis wrote The Carol of the Drum, known today as The Little Drummer Boy. Davis taught music at Wellesley College. She penned more than 600 songs. It is said she based her famous hymn on an old Czech carol. In a long-ago interview, she said the song “practically wrote itself.”

But it wasn’t an instant hit. In fact, 17 years passed before she got a phone call one day from a friend. “Kay, your carol is on the air, all the time, everywhere on the radio!” she said.

“What carol?” she asked, surprised.

Harry Simeone and Henry Onorati had turned it into a top hit, with a new title and some minor changes. Simeone even had claimed authorship. Davis eventually proved she was, in fact, the songwriter.

It Came Upon a Midnight Clear

The First Parish in Wayland, a Unitarian Universalist church in Wayland, Massachusetts, a scenic town outside of Boston, was my next stop. It was there Edmund Hamilton Sears, author of It Came Upon a Midnight Clear, served as minister.

What I love so much about the carol is that Sears wrote it as a prayer for peace more than as a carol. The Mexican War had just ended and the Civil War was on the horizon when he penned it Christmas Eve 1849.

A year later, his friend, the soon-to-be New-York Tribune music critic Richard Storrs Willis, set Sears’s poem to music.

I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day

After a visit to the nearby Edmund Hamilton Sears Chapel, I set out for Cambridge. I had an appointment to see Dr. Jameson Marvin, director of choral activities at Harvard.

“Did you know,” I asked, “that a number of Harvard professors wrote carols? Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote Christmas Bells, the basis for I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day.

“Christmas Eve, 1863, he was grieving over the death of his wife in a home fire, and of his son, who had been wounded in battle. The professor was awake late, in a desperate mood, when he heard the peal of church bells. Christmas had come.

“He sat down and penned his now-famous poem. Its last lines, famously, were, ‘With peace on earth, goodwill to men.’ Longfellow’s mood had changed.”

O Little Town of Bethlehem

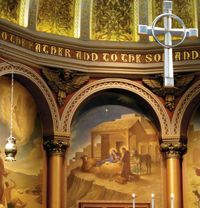

From Cambridge I drove to Philadelphia, to The Church of the Holy Trinity on Rittenhouse Square. I wanted to pay homage to Rev. Phillips Brooks, the rector who wrote the poem O Little Town of Bethlehem, after returning from the Holy Land in 1866.

Brooks had traveled there following President Lincoln’s assassination, and the deaths of so many of his parishioners in the Civil War. He was struck by how peaceful it was in Bethlehem.

“The hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight,” went his lyric—a message that he yearned for a similar peace in his homeland.

Do You Hear What I Hear? and White Christmas

I saved New York City for last. First I hoofed it to the corner of Lexington Avenue and East 50th Street, and inside what was then the Beverly and is now the Benjamin Hotel. P

ianist Gloria Shayne was playing in the hotel’s dining room. Composer Noel Regney was instantly smitten. The two married and in 1962 together wrote Do You Hear What I Hear? as a hymn to peace in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, and not originally a Christmas song.

My final stop was 17 Beekman Place, in Midtown East, for decades Irving Berlin’s home. The composer of the classics God Bless America, Easter Parade and Puttin’ on the Ritz believed his best song was White Christmas.

Christmas had always been a sad day for Berlin. He lost a son Christmas Day 1928, and over time grew increasingly reclusive. In 1983, when he was 95, carolers gathered outside his home and serenaded him with his wonderful song.

His maid invited them all inside. Berlin greeted them and told them how touched he was by their gesture. Carolers continued to serenade him through 1988, the last Christmas of his life, and still gather to sing outside his home—now the Luxembourg House, the country’s United Nations consulate.

I was back in Cape May the next day sweeping Renate into my arms.

“Thank you,” I said. “This was the Christmas present of a lifetime.”

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith