I am truly my mother’s son. I think about Geraldine Barber everyday and I don’t mean just in passing. I’ve had many fine coaches over the years—from high school to the NFL to my mentors on the Today show. Hands down, my mom is one of the most influential persons in my life.

That’s how it should be with moms, and I want to tell you about the most important lesson my mother ever taught me.

It was my fourth year at the University of Virginia, our second home game of the season, against our conference rival, the Maryland Terrapins.

It was an absolutely beautiful day and the stadium was packed. You could hear the fans stomping and yelling in frenzied anticipation as our team gathered in the tunnel leading from the locker room to the field.

The noise built to a crescendo. We were fired up like you wouldn’t believe. Guys were jumping up and down, shouting, bumping shoulder pads and helmets. At the front was our coach, poised to lead us out onto the field. The intensity in the tunnel felt like the crackling of a current.

My identical twin brother, Ronde, and I stood in the middle of it all. I was the running back. Ronde was the team’s star defensive back. We exchanged glances, knowing instantly what the other was thinking: Is one of those voices our mom’s?

Mom was at every game. She’d been to every youth league, junior high, high school and college home game we’d ever played. Mom was the rock in our lives.

But this time, her coming would be hard. Five days earlier she had undergone a double mastectomy after discovering in April that she had breast cancer. The next day she insisted on going home. “I couldn’t stand feeling helpless in the hospital with everybody fussing all around me,” she said. “You boys have a game Saturday!”

“She thinks she’ll be coming?” I asked Ronde. “She plans to drive 120 miles from Roanoke to Charlottesville, just to see us play in another football game?”

Yet the more I thought about it, the less crazy it seemed that one of those voices in the stadium would be hers.

Mom never had it easy. Her dad—Army Major Willie T. Brickhouse, Jr.—died in Vietnam in 1967, two days before her 15th birthday. She watched her mother raise seven children, including three grandkids, on her own without complaint. “That’s what families do,” Grandma said.

My dad left us when we were four. Mom was forced to do what her mother had done—raise her kids on her own. Money was tighter than Mom let on. We lived in a small townhouse in Roanoke, and throughout my childhood she worked two, sometimes three, jobs.

Days, she served as a budget administrator for the Girl Scouts of Virginia Skyline Council. Nights she worked as an inventory specialist, weekends as a clerk in a local specialty bird store.

I doubt she ever earned more than 20 thousand dollars a year, if that. We never went hungry, though, and if Ronde or I needed a new pair of cleats, she found a way to buy them.

Later, we figured she skipped a lot of lunches to provide for us. Back then, though, we didn’t appreciate her sacrifices. “Be proud,” Mom always told us. “Be proud in everything you do.”

That didn’t come easily. Both Ronde and I were painfully shy. We communicated in “twinspeak,” a barely audible mumble that few outsiders could understand.

At church we sat in the back row of the balcony so we wouldn’t have to talk to anyone. That changed when we started to come of age.

Mom made us sit downstairs in the front and say hello to the deacon or whoever else passed by once we got baptized on our 10th birthday. It was her way of making us feel comfortable around people. “You have to know how to present yourself to others,” she said, “especially in church.”

Mom’s secret was that she taught by example. She wanted us to be self-reliant, independent, hard working, brave enough not to follow the crowd. Not many athletes in our school spent their spare time reading, but we did. I was the nerdy kid, if you want to know the truth.

My mom loved books, and they were always lying around the apartment. She knew we’d pick them up. I remember finding a copy of Lonesome Dove when I was 13. I sat down with it one night and got totally caught up in the story. I couldn’t stop reading. “I wish I could write like that,” I told Mom.

“The important thing,” she said, “is that you want to excel.” She had just one rule regarding our play: We had to finish our homework first.

Like everything else, grades grew to be a competition between Ronde and me. “Hey,” I’d tweak him, “I got an A on my history test. How did you do?” It’s no accident I graduated as valedictorian of my high school class. We used to joke that Mom was behind us, pulling our strings.

She never tried to push us in any direction, though. Mom didn’t care what interests Ronde and I pursued, as long as we pursued them with passion. Our passion was sports—basketball, baseball, track, wrestling, but most of all, football.

Mom loved football too. Once, when we were 12, we watched her play in a game with other moms. Not powder puff—tackle football, the real thing. “Just so you can’t say I don’t know what I’m talking about,” she told us afterward, giving us a look.

Ronde and I went off to the University of Virginia. Mom enrolled in night school to get an advanced business degree.

Once during our first year she phoned us. Ronde and I were roommates and still competing over our grades. “I aced my test today,” she said. “How did you guys do?” Now it was Mom against the two of us.

Our third year she was diagnosed with cancer. She called one night with the news. “We’re coming home,” I told her.

She put her foot down. “I’ll have no pity parties,” she declared. “I don’t want you to come down and take yourselves away from school.” She was not going to let her circumstances, no matter how dire, dictate the way she—or we—led our lives.

Mom had never missed a college home game. But it seemed she would that Saturday after her mastectomy. Waiting in the tunnel with Ronde and my teammates for Coach to give the signal to take the field, all I could think about was Mom. No, she couldn’t possibly be there. That would be nuts.

Coach gave the signal and we exploded out onto the brilliant green field. I risked a glance in the stands. It couldn’t be! I nudged Ronde. Our mom rose to her feet, shouting, clapping her hands. She wore a goofy hat festooned with buttons of Ronde and me. I flashed Ronde a huge smile and shook my head. “Can you believe her!” I yelled to Ronde, a smile on my face.

Ronde laughed. Deep inside we both knew that Mom wouldn’t have missed the game for the world.

You’d think that once Ronde and I graduated and went into pro football that Mom might have let up a little. Not my mom.

One of her sisters died some years earlier, and after her boys proved to be too much for my grandmother, my mom took in one of her sister’s sons (the other two went off to college)—a difficult kid—and raised him as she had raised us.

Mom turned his life around. He’s in the Air Force now, and served in Iraq.

Mom’s health is fine today. She met a great guy and three years ago they married. I think it was the first thing she’d done for herself since Ronde and I were born.

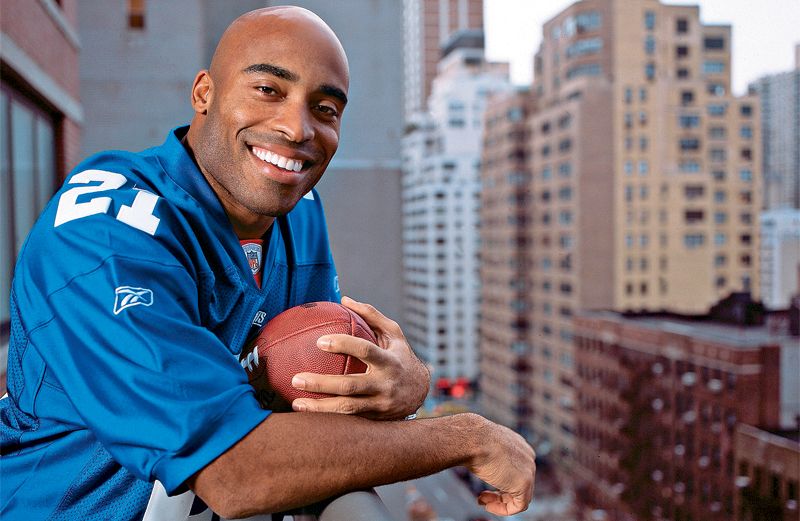

These days she spends a lot of time in Tampa, watching Ronde play for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and tries to catch me on the Today show. As you can imagine, all Ronde and I want to do is make Mom proud.

Sometimes when I look into the TV camera I think what a good thing it was that Mom helped me overcome my childhood shyness. Yes, she always seemed to know what was best.