Like most kids, I loved getting lost. Not really lost, but lost in a more intentional way. I had one favorite place to do it too: Montrose Park just above Georgetown in Washington, D.C. Montrose featured—and still features—a boxwood maze: a winding labyrinth made up of strategically planted and carefully trimmed shrubs.

Today I don’t find the Montrose maze all that intimidating. But at age four or five, it felt huge. And hugely attractive. Moving deeper and deeper into its twisting green interior, I felt the rest of the world fade away. Something, I knew, was waiting for me at the heart of that maze. And the closer I got to it—my hands now and then brushing against the tiny green leaves of the walls on either side of me for reassurance—the more excited I became.

There was something a little scary about being in that maze. That was part of its allure. Just beyond its walls my mother was waiting, and a single shout would bring her to my rescue. Because of that, I was able to savor the sense of disorientation that entering its borders created. After finding that mysterious center and emerging back into the world, I would always feel just a little larger—a little more grown-up—than I had when I had first entered.

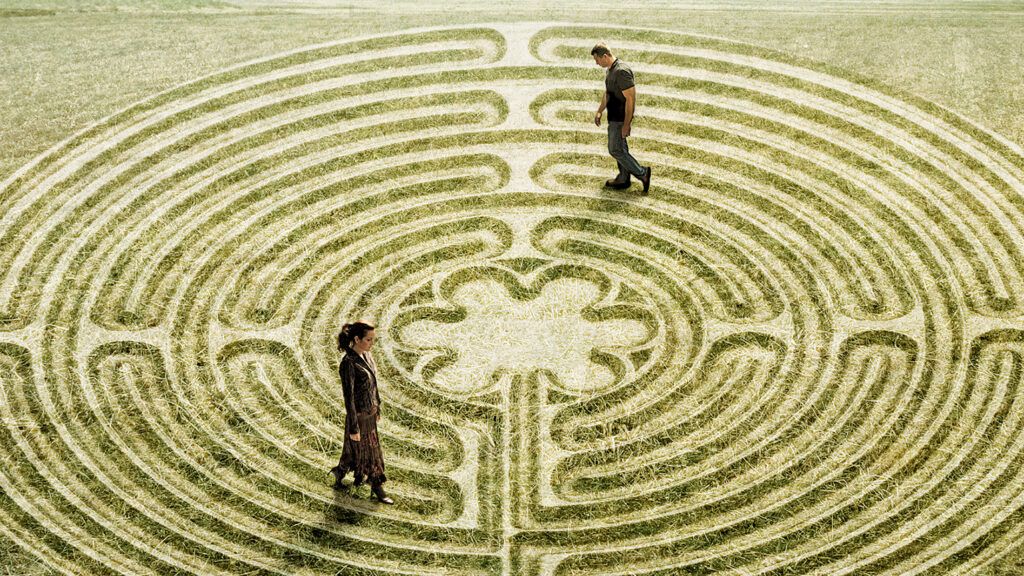

Those childhood visits to the Montrose boxwood maze came back to me recently when I paid a visit to St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Mamaroneck, New York. Several years ago St. Thomas installed a permanent labyrinth on its grounds. Unlike the Montrose hedge maze that drew me into its depths as a kid, the St. Thomas labyrinth is flat. Because there are no walls to block your view, you don’t lose sight of the outside world. You just follow along the path laid out at your feet.

There’s another critical difference: The labyrinth at St. Thomas’s has no wrong turns to it. To use the technical language employed by maze scholars, it is unicursal rather than multicursal. As much as it twists and turns, there is only one path, so you can’t really lose your way even if you wanted to. All that’s necessary to reach the center is faith in the path you’re on, and a little patience.

In spite of those differences, once I entered the labyrinth at St. Thomas, a strangely familiar feeling came over me: the same feeling I’d gotten as a kid. Once again I was moving, turn by turn, toward a mysterious center: a center that I could see as it got closer, then farther away, then closer again as I followed the labyrinth’s curves and reversals. A center that now, just as then, felt like it held some essential and enormous secret. By losing myself in the curves of the St. Thomas maze, I was finding a part of myself as well.

The labyrinth at St. Thomas Church is just one of thousands that have sprung up in recent years, ever since 1991 when Lauren Artress, the canon of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, laid down a large canvas labyrinth in the nave of the church and began teaching people the art of walking it. This canvas labyrinth became so popular that in 1994 an indoor floor tapestry was laid down in its place, followed by a permanent limestone labyrinth last year. In 1995 a stone version was also opened in the church’s meditation garden. What lies behind the allure of the labyrinth? As Canon Artress puts it, the answer has everything to do with its mysterious center. “The labyrinth,” says Artress, “teaches us that if we keep putting one foot in front of the other, we can quiet the mind and find our center.” The journey may be difficult, even confusing. But “the lesson is to trust the path.”

Both the labyrinths at Grace Cathedral and St. Thomas Church are patterned after the largest church labyrinth in the world: one that, in the early 13th century, was laid down in limestone and marble on the floor of the western nave of Chartres Cathedral in France. Both the Grace Cathedral and St. Thomas Church labyrinths are a little smaller than the one at Chartres and, of course, they’re not as finely wrought. But they also differ in another way. While the center of the labyrinths at Grace Cathedral and St. Thomas’s are empty (to suggest the mystery of the divine presence that walkers will hopefully encounter there) the one at Chartres has an indentation where a large brass medallion used to sit (it was removed during the Napoleonic wars and melted down to make cannons).

Though no paintings or drawings of the Chartres medallion have been found, scholars have good evidence for what was pictured on it: a battle between a hero from Greek mythology named Theseus and a monstrous creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull called a Minotaur. This Minotaur, legend tells us, lived in a labyrinth built by King Minos on the island of Crete. Each year Minos offered sacrificial victims to the Minotaur, until the day when Theseus braved the maze, did battle with the monster and finally slew it.

Wait a minute, you might say. What is a picture of a ferocious battle between two characters from Greek mythology doing at the heart of a medieval Christian cathedral? The answer has something to do with that slight sense of trepidation that I always felt when entering the Montrose maze as a kid. The fact is, mazes are both calming and scary—and no one knew this better than the early Christians. They saw in the story of Theseus’s journey to the heart of the labyrinth and his victorious battle with the Minotaur a parallel with another, more recent story.

In the original Christian view of the labyrinth, its twists and turns are those of earthly life (in some versions, even of hell itself), and at the heart of the labyrinth we encounter not peace and tranquility but a struggle to the death between Christ and Satan. As maze scholar Craig Wright has pointed out, “The myth of the maze expresses the hope of salvation—that eternal life will be won for all by the actions of the one savior.”

It was this reading of the story of the hero Theseus and the Minotaur that the creators of the Chartres labyrinth had in mind when they placed that seemingly incongruous image at the center of their labyrinth. In medieval Christian symbolism, the West is associated with death and the underworld. By placing the labyrinth at the westernmost part of the great cathedral, where everyone entered, the architects of Chartres were suggesting that every Christian must journey in spirit with Christ through the struggles of this earthly life—and even through hell itself—before emerging into the light of heaven (which is symbolized in the cathedral by the rose window stationed high above the famous labyrinth).

The journey into and out of the labyrinth that many contemporary maze walkers take today is, then, quite different from the one that those first creators of church labyrinths imagined. Of these two very different visions for labyrinth walkers, which one is actually correct? They both are.

As I suspected even as a child in Montrose Park, being lost in the twists and turns of life can be an adventure—but it can also be a battle. All of us get lost in life to some degree. But the promise of the labyrinth is that ultimately we do so to our own benefit. By putting our faith in the path, we reemerge from the labyrinth of life as different, larger beings than we were when we first entered it. We will lose ourselves only to find ourselves. Or as the poet T. S. Eliot famously put it:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.