I paced the long hallway outside Customs at Reagan National Airport, scanning the faces of the weary passengers streaming past me. The flight from Kabul, Afghanistan, had landed but there was no sign of Janis Shinwari or his family.

I’d dreamed of this moment for so long. My final mission, to make good on a promise I’d made five years before to the man I called brother. The man who saved my life. Now, I believed, I would save his.

Had there been some last-minute problem? The Taliban knew who Janis was, what he’d done for the U.S. military. They’d stop at nothing to kill him.

Again I looked toward the doorway. At last, at the very end of the line, I spied him, a tall man in a burgundy jacket, his wife beside him, pushing two kids in a stroller. Our eyes met.

September 11, 2001. Who will ever forget the live images on television? A jet crashing into the Twin Towers that cloudless Tuesday morning. Anger I’d never known before rose inside me. I was a pre-law student, a sophomore at an elite private college in upstate New York, 125 miles from where I grew up.

I didn’t know a thing about Afghanistan. All I knew was that I wanted to go after the bad guys. I went to an Army recruiting station. The recruiter persuaded me I’d be more valuable to the Army by completing my degree.

I joined the Army National Guard and ultimately earned dual master’s degrees in public administration and international relations. Graduated first in my class from the Army’s military intelligence officers’ basic training. In 2008, my unit was deployed to Afghanistan. Finally!

We were sent to Ghazni, a city of 141,000 people in the eastern part of the country, stationed at an Afghan Army base, living and working beside hundreds of native soldiers. Our mission was to train police officers, not for law enforcement, but as a paramilitary security force.

The hope was that one day the Afghans would be able to fight this war on their own. But it was a painfully slow process. I never went anywhere without an interpreter.

They were invaluable–not just for language but to know who we could trust, the culture, the meaning of a gesture. Men who’d left their families to work for the U.S. military, risking certain death should the Taliban capture them. But inside the base we Americans kept to ourselves.

Barely a month in, we were driving back to the base after inspecting a district police office. Fifteen soldiers in three vehicles.

I watched through a slit in our 30,000-pound, 12-feet-tall mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicle (MRAP) as the lead vehicle negotiated a fork in the road. BOOM! It flew through the air like a toy.

We scrambled to set up a perimeter, anchored by our .50-caliber machine gun. Everyone was alive, thankfully. Now we had to wait for the 101st Airborne and a wrecker. I watched for any movement in the distance, a head peeking from behind the ridgeline, sunlight glinting off the scope of a rifle, any–

BOOM! A rocket-propelled grenade. Behind us. Knocked us all to the ground. Machine-gun fire rained down. We scrambled behind one of the MRAP’s massive tires.

We returned fire, but it was like we were shooting at phantoms, the air thick with smoke and dirt kicked up by the shelling. A mortar exploded about 50 feet in front of me, leveling me.

I crawled to a ditch, firing my grenade launcher at a grove of trees to the west. The onslaught continued for more than an hour. It was terrifying. No way to tell who was alive and who was dead. My ears filled with the sounds of screaming, the ground erupting around me.

I was out of grenades. Down to my last 90 bullets. Through the haze I could see our attackers, scores of them, moving in for the kill.

I’m yours, Lord, I prayed. Comfort my family . Then out of nowhere, a truck. Thunderous, syncopated reports. A grenade machine gun. There was a heavy thump next to me, a body hitting the ground. The unmistakable sound of a Russian AK-47 firing next to my head.

I glanced to my right. An Afghani man I’d never seen before. Just a few yards behind me, two Taliban lay sprawled in the dirt, dead.

“Who are you?” I screamed.

Click here to donate gift subscriptions to Guideposts Military Subscription Program.

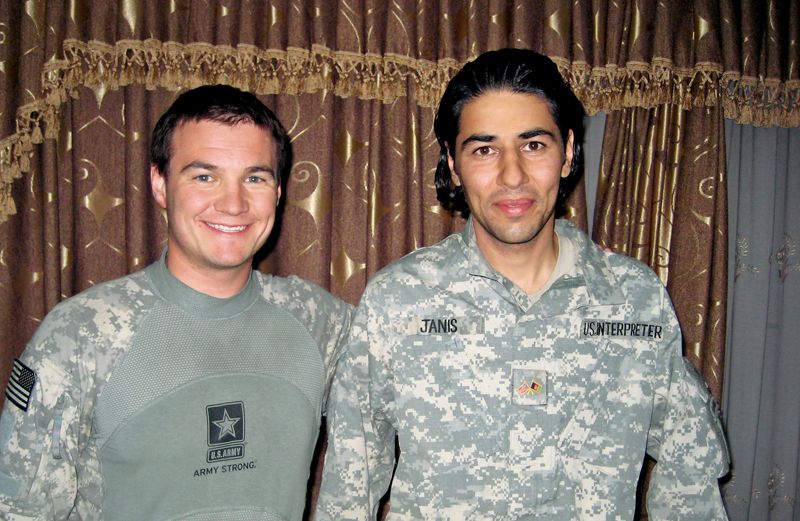

“I’m Janis,” he said. “An interpreter.”

Later I learned that a makeshift squadron of American soldiers from our outpost and a few of our interpreters, realizing from the radio traffic that air support wasn’t coming soon enough, had driven the half hour from base to rescue us.

They brought an MK19 grenade launcher, which can fire 60 rounds per minute and blow away light armored vehicles. That had turned the tide. Not a single soldier in my unit died. But all I could think about was the shots Janis had fired. The ones that had saved my life.

That night, back at the base, I sought him out, insisting we eat together. “Why are you doing this?” I asked.

“You are a guest in my country,” he said. “I will do my best to take care of you.”

“No, I mean why aren’t you shooting at us? Why aren’t you with the Taliban?”

“My mother would kill me if I joined the Taliban,” he said. “My mother can read. She’s educated. She would never let me side with these men who treat women like slaves. Or worse.”

My mother was a college professor back in New York. I thought about how she’d read books to my brother and me when we were young. How important it was to her that we got the best education possible. The conversations we’d had over dinner. Ideas, food and family, things my mother had taught me to cherish.

She hadn’t wanted me to join the Army. But in a way I was here because of her. She’d taught me the difference between right and wrong. That there were values worth fighting for.

Janis picked at the dinner. “I’m sorry,” he said. “This is not good. Tomorrow I’ll get food from the bazaar. I’ll make you a real Afghani meal.”

Janis told me that his father had been an officer in the Afghan Air Force. They’d lived comfortably, not wanting for anything. Then, with the rise of the Taliban, the tyrannical fundamentalist order that swept into power after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, they lost everything.

They’d fled to a refugee camp in Pakistan. At the camp Janis did odd jobs, earning enough money to buy a VCR. Inside was a videotape, the movie Commando, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Janis watched it hundreds of times, until he’d learned every word.

He taught himself English and graduated from high school in the camp, honing his language skills even further. He dreamed of one day being an English teacher. His family was one of the first to return to Afghanistan after the overthrow of the Taliban.

In 2005, a cousin told Janis he could make money as an interpreter. Enough to support his parents, sisters and brothers. A wife and then maybe a family of his own. He was hired, after passing an extensive security review.

His story was like nothing I’d ever heard before, a life of incredible sacrifice, hardship, struggle, so different from mine.

Sitting there next to Janis, still stunned that I was even alive, I realized how little I really knew about the people of Afghanistan, the grinding poverty they lived under, the horrific cruelty of the Taliban, the decades of war.

And yet, for all our differences I felt a connection between us, more than just gratitude, though that was no small thing. I wanted to spend more time together, to get to know him.

The next night, true to his word, Janis made us a dinner of rice, raisins, carrots, onion and goat meat, seasoned with spices he said were a secret. Kabuli pulao, he called the dish. Delicious, that’s what I called it.

We were inseparable after that. He shadowed me on every mission. We ate meals together, drank tea every evening. We talked about our faith. He a Muslim. Me a Christian. United in our belief that God held us in his hands.

Bring faith and inspiration to our troops! To donate a Guideposts subscription now, click here.

I shared the music on my iPod with him. The Beatles. Dave Matthews. U2. Songs he’d never heard before. He’d never seen the ocean, was amazed that in parts of America people could go to the beach practically whenever they wanted. I wanted to take him there, to show him a world of possibilities, of hope.

I was the hyper one, always on. He was calm, easygoing. But the danger he faced was never far from his mind.

“Last year an interpreter was seized by the Taliban while riding a bus,” he told me one night. “They castrated him, cut off his head and disemboweled him. They sent the pieces to his family and the other interpreters.”

When my eight-month deployment was over, Janis came to see me off. I threw my arms around him. “Janis, you are my brother,” I said. “I won’t forget about you. I’m going to get you and your family out of here. To America. I promise.”

“Okay,” he said. “I look forward to that day.” I watched him walk away through the streets of Kabul, a bulky leather coat his only protection.

I came back to the United States frustrated at leaving a job unfinished. I should have brought every man in my unit home, but I’d had to leave behind the one I was closest to. My interpreter, my friend, my brother.

I wanted to do something to make the world a better place. I got a job with a green-energy company. Meaningful work, but still there was something missing.

Janis and I stayed in touch through Facebook. I worried constantly about his safety, what he’d told me about the murdered interpreter haunting me. The U.S. military was closing bases, bringing troops home.

In 2011, he messaged me that he was applying for visas for himself, his wife and their two children. At last!

I knew it wouldn’t be easy. Sixteen different agencies had to approve the application, certifying that he wasn’t a security threat. He had to prove his family was in danger. I felt responsible for him. I made countless calls, to State Department officials, congressmen, the news media.

I enlisted my family and friends, the guys I’d served with. Even started an online petition that garnered more than 100,000 signatures. Still there was no word. For more than two years.

Finally, in early September 2013, he was approved. It seemed like a miracle. He sold his house. Quit his job at the base in Kabul.

Every night he and his family moved to another friend’s home, trying to stay one step ahead of the Taliban. Waiting for news of his flight arrangements from the U.S. government. Still, I thought the hard part was over.

Then, one Saturday in late September, I woke at 2:00 a.m. to my cell phone pinging. I grabbed it. Opened my Facebook app. There was a message.

“Brother, I’m terrified. I just got a call telling me to come to the U. S. Embassy and bring my passport. Our visas have been revoked. We’re dead. The Taliban is looking for me, always. They’ll kill my whole family. You have to help me.”

There wasn’t time to start over again. Just days before, Janis had told me he’d found a message scratched into the hood of his car: “Your Day of Judgment will come.” He no longer had the Army’s protection. And the base was in the process of shutting down. He couldn’t go back there.

I was frantic. I owed so much to this man. I punched in the number for the U.S. Embassy in Kabul. I explained to the Afghani receptionist why I was calling. “I don’t believe you,” he said, and hung up.

Every new message I got from Janis I worried would be his last. He’d gone to the embassy and turned in the visas. He’d heard nothing more.

Finally, someone at the State Department returned my calls. “Trust me, this is getting a lot of attention, at the highest levels,” he said. “The holdup is on the intelligence side. There was an anonymous call saying Janis is a terrorist. Someone got nervous and canceled his visas.”

The Taliban was trying to keep Janis trapped. Always attacking from the shadows. I thought of that day in Afghanistan, pinned in the dirt, down to my last bullets. That feeling of utter hopelessness. Lord, I prayed, you know the danger Janis is in. I can’t protect him. You’ve got to save him.

Late one night in mid-October my phone pinged. The last I’d heard from Janis he’d been called to the embassy to take two polygraph tests. I took a deep breath and hit the app.

“Brother, great news! The consul general called. Our visas have been approved.”

“Thank God,” I said. I ran down the hallway outside Customs to Janis and threw my arms around him. “Assalamu alaikum,” I said. May peace be upon you. Peace. An elusive dream. Yet in that moment all things seemed possible. I’d gotten the last man in my unit home.

Now I see Janis every day. But there are thousands like him still in limbo. Interpreters and others who risked their lives to help American troops are in even more danger now. We can’t leave them behind. That is my new mission. To do everything I can to make sure that these good people are taken care of, to truly be, as the Bible says, my brother’s keeper.

Matt Zeller is the founder of No One Left Behind, a community organization dedicated to ensuring that the United States keeps its promise to care for those who jeopardize their safety for our country.

Learn more about how you can contribute to Guideposts’ Military Outreach.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.