At 24, on a whim, I became the owner of a netherlands dwarf bunny named Angus. He was about the size of a baseball. In terms of personality, however, he soon established himself as a giant.

I moved around a lot in those days, and wherever I went, Angus went with me. Whether I was waiting tables in Massachusetts or working as an office temp in New York, Angus was always there when I got home, ready to cheer me up with his odd little repertoire of habits.

When he was feeling feisty, he’d charge back and forth and thump his back feet on the floor. In a more relaxed frame of mind, he’d stretch himself out like a cat. I’d sometimes wake up from a nap with him perched alertly on my head.

Then, the unthinkable. I came home to find a cloth draped over his cage. A note from my roommate lay on top. “I’m sorry,” it read. “When I got home, Angus was no longer alive.” I lifted the cloth, and there was my little ball of personality, stock-still.

In all the time I’d had him, I’d never seen Angus asleep. Even at rest, he was partly on the alert. Now, for the first time ever, I saw him with his eyes shut.

Angus’s death was something I should have been prepared for. Dwarf bunnies don’t have a long life expectancy. All the same, I was inconsolable. Just a rabbit? Forget about it. Angus’s passing hurt.

I found myself thumbing through my books on religion and mythology for references to animals and the afterlife. This is silly, I thought. But silly or not, I wanted to know what people over the centuries had to say on the matter.

Plenty. Animals played a large role in most ancient peoples visions of the spiritual world. The mythologies of several ancient cultures claimed that when people passed on, their dogs were waiting to guide them to the land of the blessed.

The Egyptians—cat people were especially emphatic in their belief that cats and other animals played a key part in the afterlife. One Native American legend states that when God set about to create the world, he brought his dog along with him.

What did the Bible have to say? On the surface at least, the Bible seems to say very little about the place of animals in the afterlife. Look up “dog” in a concordance, and you won’t find any evidence that the people of biblical times valued the role dogs play in day-to-day life.

When the writer of Psalm 22, for example, says, “For dogs have compassed me,” he is not describing a pleasant situation.

It doesn’t get much better when one looks to traditional Christian authors beyond the Bible either. Eminent churchmen like St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas have left a number of very discouraging passages about the place of pets, or any animals, in the world that waits beyond the borders of earthly life.

Though I didn’t know it then, this experience of losing a pet and coming up short on biblical consolation is one that many people have gone through. It’s also one that many have tried to convince themselves they must simply accept.

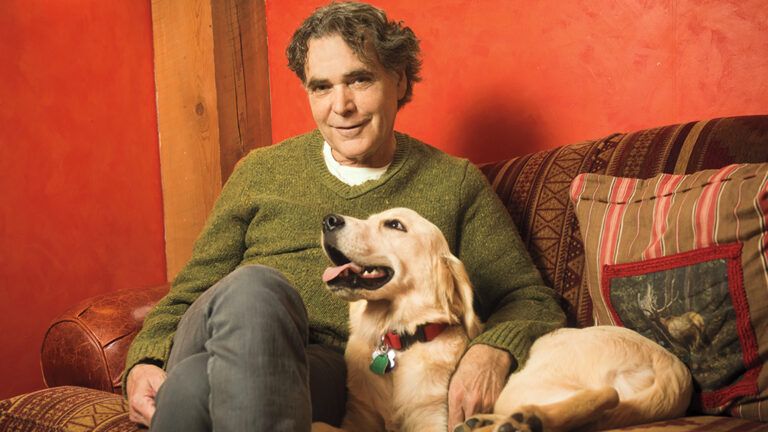

As Steve Wohlberg, author of the recent book Will My Pet Go to Heaven?, told himself when he lost his dog: “The central focus of the Bible is God, the people, and human salvation, not dogs and cats, right?”

Not so fast. Steve and a number of other writers argue that the question “Will I see my pet again?” isn’t silly, and it isn’t a question without an answer either. To discover as much, all one need do is take a closer look at the Bible.

Okay, the question of whether there are pets in heaven is never answered straight-up in the Bible. But as M. Jean Holmes, author of Do Dogs Go to Heaven?, writes, “The pieces have to be patiently gathered, carefully laid side-by-side, then prayerfully interpreted.”

The Bible does indeed have an answer about whether we will see our furry loved ones again.

Consider the story in Genesis of the very first covenant established between God and his people, made with Noah right after the flood.

The clouds part and the world’s first rainbow appears. God tells Noah that he is creating a covenant “with you, and with your descendants after you; and with every living creature that is with you, the birds, the cattle, and every beast of the earth with you; of all that comes out of the ark, even every beast of the earth.”

God goes on to say that his covenant with “all flesh” shall never be “cut off”—a strong suggestion that animals will not be excluded from his dealings with the world.

(This passage was an inspiration for “Rainbow Bridge,” an anonymous poem that has become very popular on the internet. It describes how when people arrive at the gates of heaven, the first thing they will encounter is their deceased pets.)

Then there’s Luke 3:6. “All flesh shall see the salvation of God.” Or Mark 16:15—a passage well-loved by that great friend of animals, Saint Francis of Assisi. The risen Jesus tells the Apostles to go into the world and “preach the Gospel to every creature.”

Jesus filled his teachings with references to animals. His promise in Matthew and Luke that not even a sparrow falls to earth without God’s knowing it subtly but powerfully suggests what every grieving pet owner feels: God refuses to forget a single one of his creatures, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant.

What about the argument that runs: “Animals can’t go to heaven because the Bible says they don’t have souls”? Norm Phelps points out in his book, The Dominion of Love that the Hebrew term repeatedly used to describe animals in the Old Testament is nephesh chayah.

Chayah means “living,” while nephesh is the Hebrew term for the force that animates the body—what Phelps describes as “the whatever-it-is that makes a person or an animal a conscious, sentient individual.”

A funny thing happened when this term was translated into English. In most English versions of the Bible, different words are used to translate nephesh chayah depending on whether animals or people are being discussed.

In Genesis 1:21 and 24, for example, Phelps points out that nephesh chayah is translated as “living creature.” But in Genesis 2:7, where the term refers to people, not animals, it’s translated as “living soul.”

The use of two different terms in the English translation completely blurs the fact that in the original Hebrew, no such distinction exists.

Why did the Bible’s english translators take such pains to use different terms for the souls of animals and people, when the Hebrew of the Old Testament repeatedly uses just one? Probably because they were concerned not to contradict Genesis teaching that humans alone are created in God’s image.

But to acknowledge that animals have souls isn’t to usurp the unique place of humans in God’s creation—as the original Hebrew makes clear enough.

Of all the biblical passages that I ultimately discovered I could turn to for consolation, the most moving and compelling is the Old Testament’s single greatest passage prefiguring the Christian heaven—Isaiah’s vision of the Peaceable Kingdom:

“The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.”

Why, when Isaiah wanted to paint the ultimate picture of heavenly fulfillment, did he choose to make such rich use of animals? Because he knew what every pet owner knows: A world without animals is a barren one. And clearly, a heaven without our pets would be less heavenly.