You never know what you might learn at the dog run.

I’d taken Gracie to the Chelsea dog run in Manhattan on a beautiful spring morning perfect for doing nothing but watching the dogs play and cavort. The dynamics of a neighborhood dog run delight me. First there are the dogs and the complex social relationships that ebb and flow day by day. You can see who’s a friend and who’s on the outs. Who’s popular and who’s not so much. Who’s an extrovert and who’s an introvert (is there a Meyer-Briggs test for dogs?). Occasionally there is a scuffle, but it rarely amounts to much and seems to generally clear the air of whatever conflict triggered it.

Then there are the social relationships of the owners, not so dissimilar from the dogs. You could demonstrate the overlap using a Venn diagram, but we don’t have time to go into that.

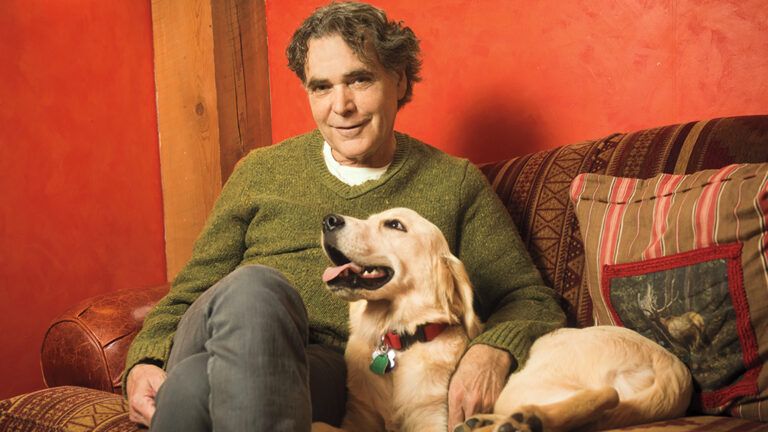

That day I sat on a bench with one other person, a man who was reading on his phone, and watched my golden charge into the canine throng, quickly convincing some of the other big and even not-so-big dogs to chase her. She loves the attention and is as swift as the wind.

The man looked up from his phone and scanned the run then called out, “Buddy!” a couple of times. I tracked his gaze to an older dog standing alone in a corner of the run, seemingly staring at the ground. “Buddy!” The man whistled and clapped. No response. I wondered if his dog might be deaf. Finally, he got up and walked over to Buddy, knelt by his side, and talked softly to him. He slipped his fingers under Buddy’s collar and gently led him back to our bench.

Buddy was a lab mix of some sort with a graying muzzle that melted my heart for after all there is nothing sweeter than an elder dog. He seemed happy and relieved to be back with his human and curled up at his feet contentedly. Perhaps he was blind, so I asked.

“No,” the man said. “He has dementia.”

I was surprised at my own ignorance. Of course. Our pets suffer many of the same ailments that afflict us: diabetes, arthritis, thyroid problems (Gracie), kidney disease, cancer.

“He’s almost fourteen,” the man, whose name was Lyle, said. “I rescued him when he was about seven thinking I’d be lucky if he made it to ten. He’d been abused. I guess all he needed was a little love.”

I leaned over and ruffled Buddy’s neck. He looked up appreciatively.

“It happened so quickly,” Lyle said. “My partner noticed it first. Buddy would get disoriented in our apartment. I mean, it’s a New York city apartment. Hard to get lost in one of those.”

“He still has his appetite?” I asked.

“Oh, yeah. I can’t say no to him. He’s getting a little porky.”

We both laughed. Dogs. Food is everything.

“He’s developed an anxiety disorder. He paces a lot and doesn’t sleep well at night. Or he just stares. Sometimes he barks and barks until you calm him down. Never did that before. I think he hallucinates, and the vet said that was possible.”

Gracie trotted over to check in and say hello to Buddy. She’s so good with older dogs who might not be as active as she is. I do not like to think of her getting old.

“He always loved the run so I bring him here as much as I can though it tires him out some.” Lyle took out Buddy’s leash. “Our vet is great though there’s not much she can do. All we can really do for him is give him a lot of love and reassurance. Sometimes we take turns staying up with him at night.” Lyle smiled. “I’ve been catching a lot of old movies.”

It struck me that Lyle and his partner were caregivers, like so many of us these days, being there for the people and animals we love, being there because we are needed, and it isn’t in us to say no.

“I’ll know when it’s time,” Lyle said, clipping Buddy’s leash to his collar. “When I think I’m keeping him alive just for myself, then I’ll know it’s time.” With that he and Buddy headed off.

“I’ll say a prayer for Buddy,” I said, waving, but I don’t think he heard me.

Canine cognitive dysfunction (CCD) is more common as our dogs live longer. Like Alzheimer’s, with which it shares many symptoms, it is incurable, and the underlying pathology is similar. There have been small but promising trials using stem cells in dogs with CCD, and this has led researchers to speculate that stem cell therapy could possibly be used as an intervention for humans suffering from Alzheimer’s and other dementias. But that day is a ways off.

As I write this book on Alzheimer’s it occurs to me that it deserves a chapter on the dementia that afflicts dogs, something I didn’t initially plan. We love our dogs so deeply and when they suffer something like CCD, we suffer with them and do all we can to help. So, I have a request. If you have had experience in this area as a caregiver for a dog with cognitive dysfunction, please let me know by writing me here. I might be able to use your story in the book, and I would love to hear from you in any event.