Mrs. Naman, we need you to come to the high school—immediately.”

The phone call was from the secretary at my 15-year-old daughter Natalie’s school.

I have three children, one older than Natalie, one younger. I had never been summoned to a school office before. And certainly not for anything like this. It just wasn’t possible!

I called my husband, Peter, a surgeon at the hospital in our Pittsburgh suburb. “Meet me at Natalie’s school,” I said. “They said she was caught with substances. What does that mean?”

“Not good,” said Peter. “I’ll be there.”

Natalie was in the principal’s office, surrounded by school officials and three police officers.

I couldn’t process everything they were saying. “Possession…heroin…backpack…zero tolerance…suspension…charges.”

On the principal’s desk were small packets of white powder, a spoon and syringes.

This couldn’t be happening. There had to have been some mistake. We were a loving, happy family from a nice neighborhood. Peter was a respected doctor. I had dreamed of becoming a mom my whole life, and I had worked hard at it. Natalie was a wonderful child. Bright. Creative. Game for anything. Practically perfect.

“Are you sure?” I asked the circle of stern faces. “Natalie is a good girl. I never saw any sign of this.”

“Parents often don’t,” one of the police officers said matter-of-factly.

On the way home, Natalie insisted it was all a mistake. “It wasn’t mine, Mom,” she said. “Someone asked me to hold it for them. I don’t have a drug problem. You’ve got to believe me!”

“If she’s injecting heroin, that’s serious,” Peter said later that night. We’d stayed up talking to Natalie; now it was just the two of us. “Heroin affects the brain in unique ways. It is very addictive, especially for adolescents.”

“She told us it wasn’t even hers,” I said. “Shouldn’t we give her the benefit of the doubt?”

I remembered occasionally finding little packets in Natalie’s room like the ones I’d seen on the principal’s desk. I’d had no idea what they were and left them alone. I suppose I hadn’t wanted to know. I’d put them out of my mind.“

Natalie needs to go into treatment immediately,” Peter said.

“She’s not some junkie,” I said. “What will her friends think? Everyone will know! She’ll be an outcast.”

Peter shook his head. “We need to intervene as soon as possible,” he said.

Reluctantly, I agreed to enroll Natalie in an outpatient treatment program, the least disruptive option. I certainly wasn’t going to send her away to some facility. There would be so many questions.

And I insisted that Peter and I tell only our parents, no one else in our extended family or circle of friends. Other families at school would find out through the rumor mill, but there was no need to tarnish Natalie’s reputation.

I went to bed shaken but determined to turn this situation around. I also felt something I hadn’t experienced before. Anger toward God.

“How could you let this happen?” I demanded. “I did everything right.”

I had worked so hard to be a perfect mom. I’d been a teacher before the kids were born, but I’d quit to raise them. My dream was the kind of family you see in Hallmark movies. I’d planned so carefully, so perfectly. This couldn’t be happening. Not to us.

October? Time to pick pumpkins and decorate Halloween cookies as a family. Christmas Eve? Arrive at church early to get front-row seats. I made meat loaf from scratch, baked, always brought treats for school parties. I covered all the bases. Heroin wasn’t part of the plan.

What I couldn’t accept was how all of those positive experiences had led Natalie to…drugs.

“It’s my fault,” Peter said. “I should have been home more.” His hospital schedule was demanding.

“I was the one who was home with her,” I said. “Which is worse?”

For a while, it seemed as if my instinct to keep things quiet and give Natalie a chance to do better was working. The school wanted to turn her suspension into an expulsion, but we convinced the administration to allow Natalie to become a full-time online student.

She was charged with drug possession, convicted and sentenced to probation with treatment, which she was already doing.

Natalie seemed relieved to be out from under the social pressure of in-person school. A boy asked her to a dance. We let her go and even invited other families to gather at our house before chaperoning the kids. Some of the moms seemed standoffish or awkward, but others were nice. How many people knew about Natalie? Inside I cringed. Shouldn’t this be a private matter?

I tried not to notice at first that Natalie’s grades were slipping. (She was just struggling with remote learning, I told myself.) Or that she was staying up later and leaving the house with people I didn’t know.

Then I found a syringe in Natalie’s room. I confronted her, and she insisted she had no idea how it got there. I wanted so badly to believe her, but Peter warned me that things were getting worse.

Soon the signs were unmistakable, even to me. Natalie began nodding off during meals. Disappearing for an entire day or night. She began to look haggard.

I worked harder and harder. We took her to psychiatrists and counselors. I relented and agreed to send to her to an inpatient treatment program. I was desperate, desperate to turn all this around, to get back to the way I thought things were.

I tried to reason Natalie out of using. Begged. Cried. Issued ultimatums. I scoured her room for drug paraphernalia. Stayed up all night waiting for her to come home.

By this point, I’d given up on God. One Sunday, our priest said in a sermon that sometimes God comes alongside us in suffering but doesn’t immediately solve the problem.

Well, he should, I thought bitterly.

I felt as if we were in this alone. “Where do you even get drugs?” I asked Natalie one day as we drove to the store. I couldn’t imagine drugs being sold in a town like ours.

“You mean walking distance or driving distance?” Natalie responded. I looked at her in shock.

“It’s everywhere, Mom. So many kids my age take drugs. Families here have tons of money, and parents have no idea what’s going on.” We passed a house, and her face darkened.

“What?” I asked.

“The guy in that house will sell you any drug you want,” she said. “See why it’s so hard to quit?”

After yet another relapse, Natalie began telling me, “I just want to close my eyes and never wake up.”

One Saturday morning, I peeked into her room and saw her motionless on her bed. Her skin was purple.

“Peter!” I shrieked. Natalie had overdosed. Peter rushed in with a container of Narcan, and Natalie revived. I staggered out of my daughter’s room and collapsed in the hallway.

I began to cry. I couldn’t stop. I lay on the floor unable to move. Just like Natalie, I wanted to close my eyes and never wake up.

That thought frightened me. I sat up. “I have to go out,” I told Peter. Natalie was stable and under his observation. I drove straight to our church. The sanctuary was open but unlit. I walked to a pew and got on my knees.

A sensation of utter weakness and imperfection engulfed me. I was broken. Natalie was broken. Our family was broken, and I couldn’t fix or even hide the problem.

“I can’t do this on my own,” I said to God. “Please give me your strength and wisdom.”

I didn’t hear an answer. But on the drive back home, I began to feel more clearheaded. I had been trying to do the impossible: fix someone else’s addiction. I had gone against everything the professionals told us. I’d downplayed the severity of the problem. Denied, denied, denied. Kept things quiet. Tried to force Natalie to get better.

I had turned away from the one thing I needed most: trust.

I had not trusted God—my biggest denial of all. I had not trusted our friends or extended family enough to be honest with them or ask for help.

And I hadn’t trusted Natalie. She was an adolescent and needed guidance and love. But if she was going to get better, the change would have to start with her. I couldn’t will her into recovery. I wasn’t in control.

I wish I could say I returned from the church transformed into exactly the mom Natalie needed me to be. That’s not how it works. I’d simply taken the first step on a long journey. That meant trusting my daughter to God.

It took another overdose and more than a year of relapses before Natalie finally decided, on her own, that she’d had enough and wanted to get better.

Along the way, I gradually figured out how to help her. I attended support groups and talked to a therapist. I worked on setting aside my drive for perfection that made it so hard for me to let Natalie make her own decisions. I stopped denying that we weren’t the perfect family.

How long had I burdened Natalie with my outsize expectations? Probably her whole life.

“I can’t fix this for you,” I told her. “But I love you, and I’ll be at your side when you’re ready to try.”

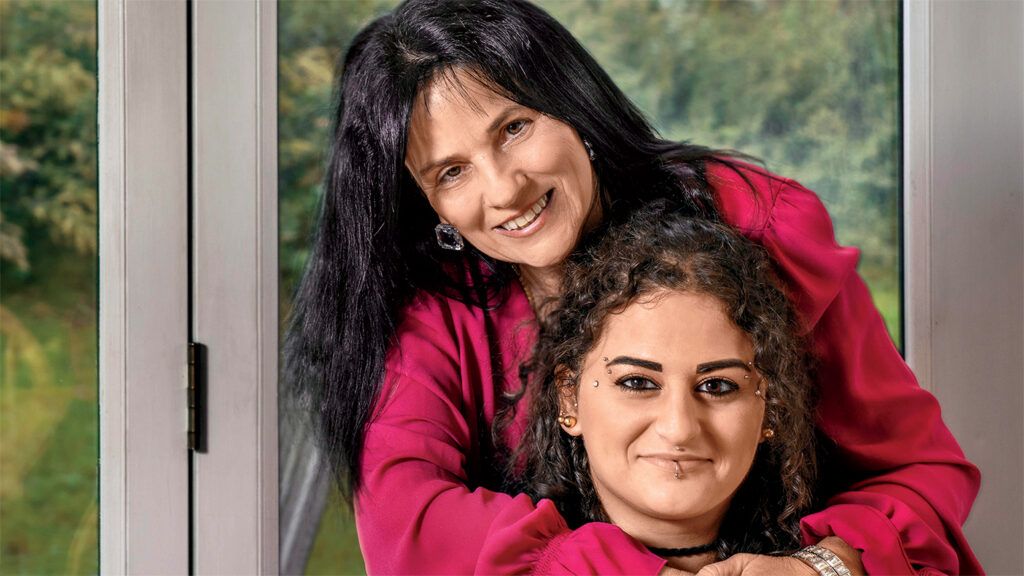

By the grace of God, Natalie is two and a half years clean now. She decided to enter a treatment program, and she is determined to remain sober. This year, she started taking community college classes.

Our family remains a work in progress, but I have hope. Why? Maybe it’s moments like a recent afternoon when Natalie and I were on our way home from running errands.

“One more stop,” I announced as I pulled into the church parking lot. We had parked in this exact spot at church many times over the years of my daughter’s addiction. I had always invited Natalie to come inside. Mostly she stayed in the car and played on her cell phone. I knew better than to ask this time. “Just going inside to pray for a few minutes,” I said. “I’ll be right back.”

“Wait,” Natalie said. “I’ll come.”

I did my best to hide my elation.

The sanctuary was open but unlit, just as it had been on that day she’d overdosed. We knelt side by side. I wondered what she prayed for, but I didn’t ask.

Together we lit two candles near the entrance and watched their soft glow.

“I prayed for you,” Natalie said as we headed back outside. She reached out to take my hand.

“Me too,” I said, giving her hand a squeeze.

We approached the car.

“He hears us,” Natalie said.

“He does,” I said.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.