It wasn’t as if this was my first time. My first time in rehab had been 16 years before. I snuck out of the place on my twenty-first birthday, promising my brother Russell I’d never use again. It all felt so familiar. The 12-step slogans on the wall: One Day at a Time, Easy Does It, Let Go and Let God.

The chairs set in a circle for the mandatory group meeting. I’d only been in Hazelden, a rehab center in Minnesota, a week. You’re supposed to count the number of days you’ve been sober. Me? I was counting down the days until I got out.

“Danny, you need to identify with these other addicts and alcoholics,” a counselor had told me. “You’re different people with the same disease.” But I’d never done any of the stuff these folks were talking about. I never robbed or lived on the streets or got my dinner out of a Dumpster.

I came from a solid background. I had a house, a good job, a master’s in public finance. I painted and wrote poetry. Yes, I broke my promise to Russ. I used heroin, and some other substances. I thought I had it under control. I did have it under control. Until suddenly I didn’t.

READ MORE: ANDREW ZIMMERN’S ROAD TO RECOVERY

My mind drifted as the meeting began and people started to share. How did I get here? Back in the sixties, when I was coming of age in New York, everyone I knew was getting high. We were activists by day, hippies by night, hanging out, listening to all that great new music that seemed to define the era. Like the song said, it was the Age of Aquarius. We believed it. I thought getting high fed my creativity, helped define me as an artist. Yet there was another reason I did it too. Pain.

I was into sports as a kid and broke both hips by age 15, developing arthritis soon afterward. Pins and hip fusions didn’t work. Drugs did, though, which was one reason I went into rehab the first time. In my early thirties I had the first of several hip replacements.

Because I was an addiction risk when it came to opioid painkillers, they were doled out to me in limited quantities and for as short a time as possible. Man, I did everything I could to endure the pain. Finally it was too much. I turned to my local pharmacy—the corner. No prescription required.

Well, maybe I’m not being totally truthful. After that promise to my brother Russ, I dabbled in all kinds of drugs. More than dabbled. Even after I earned a degree and got a job in social work, even after I got married and had a son, I used—marijuana, cocaine, psychedelics. You name it, I used something almost every day.

Heroin, though, that was my downfall. That’s how I ended up here at Hazelden. I’d tried it as a teen, then quit when I made that vow to Russ. Then came the hip surgeries and the pain, and I knew exactly what to do about it. I thought I’d do heroin for one night, just to get some relief. One night turned into three years. Finally my family stepped in, but only after I lost my marriage and practically everything else.

The guy next to me was talking. “I feel like it’s impossible to stay clean. This is my fourth time in rehab and…”

Well, this was going to be my last time. This was just a little rest stop. If I played the game for another 21 days I’d get out and stay clean. Maybe mess around here and there with softer drugs. Nothing serious. I’d get my life back on track. I still had a house…barely. I still had a job in social work if I wanted it… barely. I’d give it five years. Five years clean and then I’d try heroin again, just on the weekends, here and there.

Suddenly it was as if someone had slapped me. No, as if I’d slapped me. Here I was in a 12-step rehab meeting, seeing myself five years into the future, and all I could really imagine was buying a bag of dope, obsessing on exactly how it would feel when the drug hit my brain, practically drooling at the prospect. Who thought that way? An addict thought that way, that’s who. Only an addict. Chances are, if you think like one you are one.

Now the counselor was speaking. His words cut right through my zone-out. “Once you’re a pickle, you can never go back to being a cucumber.”

That had to be one of the silliest things I’d ever heard, one of those things they’ve been saying in 12-step meetings for years. And yet it made total sense to me. I am a visual person. I formed a picture in my mind of a cucumber. I saw its texture, its shades of green. I could almost touch it. Then I imagined it soaked in vinegar until it got all gnarly and acidic. Until it was, irrevocably, a pickle. There was no way for it to be a cucumber again.

I glanced at the dude next to me who said this was his fourth trip to rehab. Would I have a fourth trip? Or a sixth? Or a trip to the morgue? My addiction was stripping everything meaningful from my life. I’d stopped being a cucumber a long, long time ago. I was in denial. Yes, I was in denial that I was a pickle. I had to stop myself from laughing out loud.

I looked around the room. I could definitely identify. We were all pickles. And it felt good to know that. I’d been running my whole adult life from who I was, an addict, and the further I ran the more I used.

I stared at one slogan: Let Go and Let God. Two separate acts. Except they weren’t. I couldn’t do one without doing the other. Only a higher power could remove my desire for drugs, a power much stronger than my addiction. I always believed in God—or said I did. Had I ever really trusted him? Was trusting God the only true way to believe in him? This was my moment of clarity that recovering addicts and alcoholics talk about, the freedom of surrender.

I finished my stint at Hazelden, humble, grateful, sober. There’s another recovery slogan that says, People, Places and Things. It means that it’s not really the drug that gets you high. It’s the people, places and things that lead you to the drug. Using is just the end result.

How true that was. My neighborhood was wall-to-wall people, places and things I associated with drugs. There was no going back there. Not then. So I moved out of my brownstone in Brooklyn and moved in with my mom in Queens, one borough over. I guess I let go and let Mom too. She kept an eye on me, made sure I took care of myself, an important part of early sobriety. About the only time I left the house was to attend recovery meetings.

Russ would come by and give me encouragement. He and Mom gave me time to heal and to hide out a little bit too, I guess.

READ MORE: GIVING HIS ADDICTION UP TO GOD

One night Mom said, “So now what, Danny? You’ve been given so much. What are you going to do with it now that you’re sober?” I sat there for a cool minute. I needed something to focus my life on. But I had to trust that I was being led in the right direction.

“I want to leave social work,” I said. “I want to be a full-time artist.”

“Go ahead,” Mom said, smiling. “Nobody will let you starve. Paint if that’s what you feel called to do.”

I moved into a loft in a new neighborhood in Brooklyn and stocked up on art supplies. Then I faced one more moment of truth. Could I create art without drugs? I’d never tried. I wasn’t even sure I believed I could.

Instead of cutting lines of cocaine or heroin on a table, I squeezed warm tones of paint onto a palette—orange, red, yellow. I ran my hand across the freshly primed canvas. Smooth, clean, ready to be transformed. I looked at the brush in my hand. It wasn’t just a brush. It was a choice. It could have been a pipe or a spoon. It could still be.

I dabbed it into the red paint and swirled it on the canvas. I added blues and purples, shapes and shadows, texture and movement. I felt as good as I ever had, like the story of my recovery was unfolding right on that canvas.

A few months later, I had my first sober show and it was a hit. The next one sold out. More shows—and success—followed.

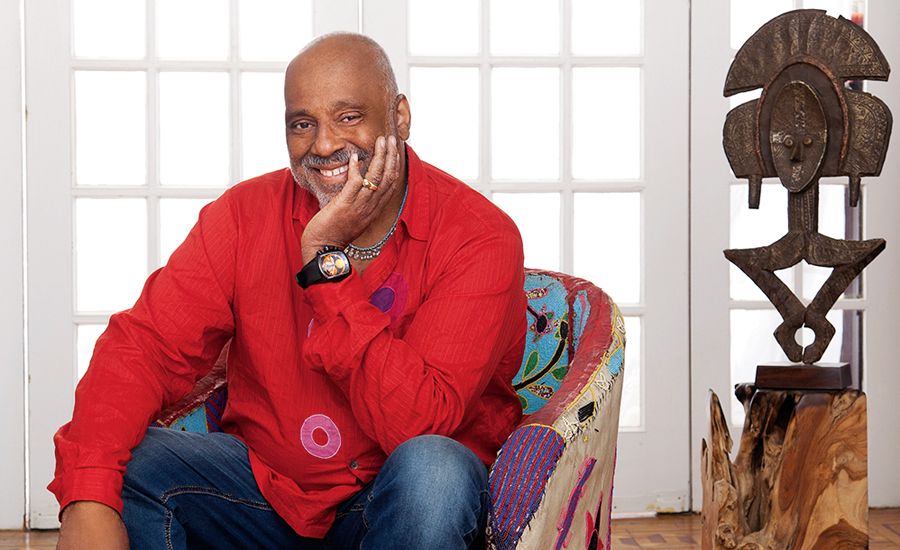

Sobriety was a gift I needed to give back. I got together with my brothers, Russ and Joseph “Rev. Run” Simmons, and we created Rush Philanthropic Arts Foundation, to provide disadvantaged youth with exposure to the arts; Rush Gallery in Chelsea and Corridor Gallery in Brooklyn, to support emerging artists. I want to give people the chance to make the same choice I did, by the grace of God.

Today, the Rush Foundation is 20 years strong and I’ve been clean for 22 years—a happy pickle, one day at a time. The pain is still there, but I can deal with it. That’s the thing about this new life: It’s the greatest high I ever had.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.