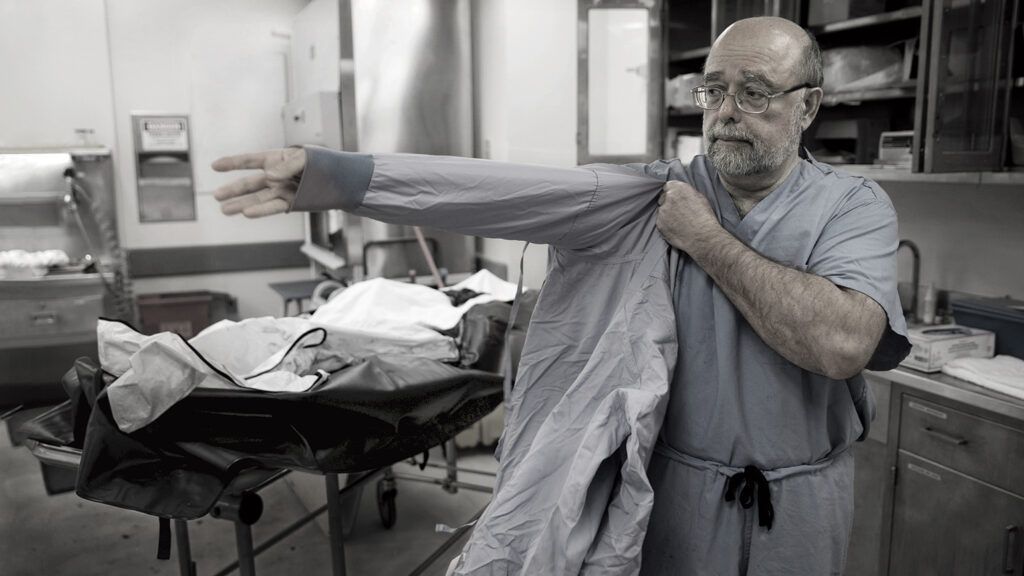

For two decades, I worked as what I call an accountant of America’s opioid crisis. From 1997 to 2017, I was the chief medical examiner for the state of New Hampshire. I oversaw autopsies. My department’s job was to determine and officially certify the cause of death.

New Hampshire is a small state. In 1997, the population was almost 1.2 million. (It’s a little more than 1.3 million now.) When I started as chief medical examiner, the department saw roughly 30 to 40 drug-related deaths per year. Then, suddenly, in the early 2000s, after pharmaceutical companies began heavily marketing opioid pain medicines, the number of drug deaths shot up to 200 per year. They kept climbing. By 2015, they were at 439 per year. Last year, 487 people in New Hampshire died from drug-related causes. That’s more than one drug-related death per day. A one thousand percent increase in two decades. One thousand percent!

Community Newsletter

Get More Inspiration Delivered to Your Inbox

I learned to recognize the telltale signs of opioid abuse. Needle marks. Bruising in areas associated with injection. Inflamed or damaged sinuses from snorting drugs. Signs of respiratory failure—most overdose victims die from lack of oxygen to the brain.

I did my job with professionalism and medical objectivity. But the work took its toll. I’m a Christian, strongly influenced by my upbringing and youth spent as a Boy Scout. I believe in serving others. Examining the bodies of overdose victims, I often felt helpless. I could determine how people died. I couldn’t stop the deaths from happening.

I told myself when I took over my department that I would stay in the job no more than 20 years. In my view, public servants shouldn’t consider their jobs lifetime appointments. Organizations need new leadership to change and grow. I knew I would retire in 2017.

What I didn’t know is what I’d do next. After much thinking and praying, I enrolled in seminary, intending to become a Methodist chaplain and work with young people. What explains such an unexpected turn? I’d spent my career investigating death. Turns out, the job was preparation for something else—steering people toward life. Growing up, I was blessed by several influential mentors.

My parents were examples of strong faith and devotion to family. The minister at our Presbyterian church—a tall, authoritative, deep-voiced Calvinist named Reverend Nicholson—taught me Scripture and the basics of Christian life. Reverend Baer, the minister at the Methodist church that hosted my Boy Scout troop, showed me that a pastor can be young and cool as well as spiritually grounded. He even let me give the sermon at his church on Scouting Sunday when I was 14.

There was my beloved Boy Scout troop leader, Alva Butt, whose example also guides me today. Alvie, as we called him, wasn’t the kind of youth leader who tries to impress kids with his hipness or his skills. He was sort of goofy, just like us boys. He never raised his voice. Never got angry—no mean feat when you’re shepherding a dozen or so teen and preteen boys through the wilderness. And yet we always knew who was in charge. And we always knew how Alvie wanted us to behave—with kindness, courtesy and trustworthiness, according to the Scout Law. Alvie inspired us to be our best selves.

I considered going into ministry or youth leadership myself as I left for college. But I was a science nerd at heart, and medical school captured my interest. I began my medical career as a pediatrician, working with kids. The job was rewarding—and frustrating. Time with patients was limited. There were endless hassles with insurance.

I’m a methodical person. I try to look at issues from all sides. I could not do that in the rush of primary care, so I went back to school, studied anatomical pathology and became a forensic pathologist under the wing of my most influential mentor, Dr. Charles Hirsch. I worked in three medical examiner branch offices in New York City before coming to New Hampshire.

I love pathology. It’s like detective work. Clues are everywhere: on the skin, in the organs, in the blood. A pathologist must be thorough, ruling out nothing. It can take a long time to determine a definitive cause of death.

Opioid drugs stimulate the release of naturally occurring mood-regulating chemicals in the brain. The drugs do this by attaching to neural receptors, flooding the brain and altering perceptions and responses. One receptor that opioids attach to is the mechanism regulating breathing. The opioids slow breathing, part of their overall depressive effect. Take too much and breathing will slow until the brain is starved of oxygen—hypoxia. Unless the drug user is revived by an opioid-reversing medication such as naloxone, he or she will die of asphyxiation. That’s why so many overdose victims turn blue.

I saw few such cases when I started work in 1997. After the turn of the century, the number began to increase. I didn’t understand why at first. Then I began reading news stories about OxyContin, a new long-acting opioid pain medication being marketed to primary care physicians. The medication was said to be nonaddictive. But I was seeing clear signs of addiction and abuse. The overdose victims I examined had large amounts of opioids in their blood, far more than would be expected if they’d taken the drug as directed.

As regulators began cracking down on prescribing procedures, I saw a growing number of heroin overdoses. Unable to get pills, users were switching to powerful street drugs in the opioid category.

“If we keep going like this, overdose deaths are going to outnumber traffic deaths in New Hampshire,” I told a reporter in 2004. The comment—a heartfelt expression of alarm—went viral. People were shocked, incredulous. A high-ranking federal drug official even traveled to New Hampshire to meet with me and learn more. No one could believe the situation was that bad.

The very next year, it happened: More people in my state died of overdoses than in traffic accidents. Was this just a New Hampshire phenomenon? No. The same became true for all of the United States in 2009. In 2016 alone, the last year for which statistics are available, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 63,632 Americans died from drug overdoses. That’s 5,000 more than the number of soldiers killed throughout the entire Vietnam War.

Imagine if the number of traffic deaths skyrocketed by one thousand percent in 20 years. In fact, in 2014, 10,000 fewer people were killed in traffic accidents than in 1997. American car manufacturing is highly regulated by government safety standards, roads are heavily policed and drivers are subject to traffic laws. Our nation has not yet committed to a similar solution for the opioid crisis.

Watching overdose victims appear in my lab at an ever-rising rate, I grew increasingly frustrated. Yes, I could recognize the signs of an overdose, examine victims and arrive at a carefully determined cause of death. But by the time people came into my care, it was too late. They’d already paid the awful price of addiction. I was the cleanup crew.

I did my best, though not always successfully, to hide my stress from my kids. I unburdened myself to my wife. And to God in prayer. That faith I learned from my mentors growing up? I leaned heavily on it as my work grew more challenging. Approaching retirement, I became increasingly convinced I didn’t want to end my working life as an accountant of death. I wanted to prevent people from ending up in the forensic lab. I wanted to address the spiritual dimension of the crisis, reaching kids before drugs did.

How could I do that? I thought back to Alvie. How his gentle but unwavering leadership, his dedication to us boys and his selfless example of service had inspired me. Could I do the same for kids now? New Hampshire has one of the lowest churchgoing rates in the U.S. If I wanted to reach kids with a spiritual message I would have to go to seminary—then work in an organization outside the church. Like Scouts.

That became my plan.

I retired in 2017. That year, New Hampshire had the nation’s highest overdose rate after West Virginia and Ohio. My successor in the forensic pathology office has been confronted by so many overdose deaths, her staff is barely able to keep up with the workload. The arrival on the black market of fentanyl—a potent and deadly synthetic opioid marketed and sold like heroin—has deepened the crisis.

I enrolled in a seminary in Dayton, Ohio, where I grew up. I take some online classes and commute to Dayton to be on campus. I’ve completed nearly one year of studies. It feels strange to be writing exegesis essays on biblical prophets after all my years investigating death in a forensic lab.

I’m focused on life now. For so many years, I watched America’s drug crisis unfold before my eyes. For just as long, I have believed that this crisis does not have to get the better of us.

The Boy Scout Oath says, “On my honor, I will do my best to do my duty… to help other people at all times.” If we live by that, if we give this crisis the attention it deserves, reaching out with love and compassion for those caught in the web of substance abuse and their families, we can make progress. The number of deaths doesn’t have to rise inexorably. The tragedy of addiction doesn’t have to claim a generation.

I was an accountant of death. I’m ready now to help prevent it.

4 Tips to Help Protect Your Kids from Drugs and Alcohol

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.