Again, let me thank you for so many responses to recent blogs. Thanks for all the tips on making lists—you folks sure are list makers, and you have brought me into the fold—and for sharing how you feel about a possible Alzheimer’s vaccine. Most said you would take it. I would too even if I were the very first subject in an experimental trial. Sign me up.

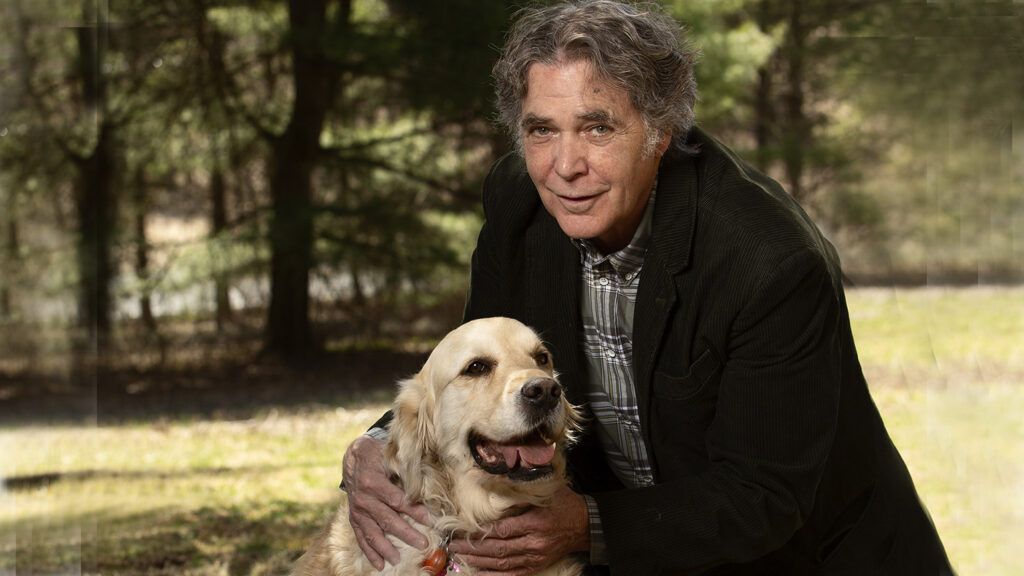

Maybe my eagerness stems from the fact that I couldn’t find the keys to the Jeep this morning to take Gracie for her hike. It’s not the first time in my life this has happened, of course, but these days any lapse can unnerve me. “Gracie, where did I put them?” I knew she knew. If only she could tell me!

At last, I found them in the place I should have looked first, adding to my frustration. But it jarred loose a very painful memory: having to take the car and car keys away from my mother as Alzheimer’s impaired her driving skills. And Mom was quite the motorist.

Mom didn’t learn to drive until her forties when Dad finally relented (Dad was old school on the matter of women driving and, besides, Philadelphia had trolley cars if you needed to get somewhere). He got her a used black-and-red Plymouth and the first time out solo after getting her license she rear-ended a cop.

We moved to Detroit where cars were imperative (trolleys and mass transit broadly were frowned upon by the automakers—not in their backyard!). Mom drove everywhere, especially after Dad died. She was always going somewhere, starting with church every morning.

The call came from my brother. “We’ve got to get the keys away from her.” In truth we’d already waited too long and to this day my brother and his wife, both civil litigators, can’t believe we delayed so long. But who wants to confront a parent on such a fundamental freedom?

There had been incidents, starting with not being able to find the car in the parking lot of T.J. Maxx and calling 911. There had been some thankfully minor fender benders and unexplained dents and scrapes. She drove through the back of the garage…twice (it was, she explained, the car’s fault). Finally, one morning she sideswiped a cop—yes, a cop again—kept driving on until the cop caught up with her, denied the incident happened, then blamed it all on him for being such a careless driver.

I flew to Detroit. Julee stayed in New York with the dogs. I think it would have broken her heart to have confronted Mom. My brother, Joe, his wife, Toni, and my sister, Mary Lou, all went to Mom’s for dinner. Sitting around the table afterwards, Joe broached the subject.

I think Mom was expecting it. She’d seen it happen to her two older sisters, especially Cass, who was the Welcome Wagon lady in Paoli, Pennsylvania, at the end of the Main Line and wanted to die rather than surrender her keys.

Mom jumped up from the table and retreated to a corner of the kitchen where she seemed so much like a frightened, cornered animal. We were her children, and we would not take her car, her freedom. We would not! Mary Lou explained that her license was already suspended due to the incident with the cop and the only way to get it back was to pass a new driving test at the DMV.

I saw the surge of hurt in Mom’s eyes, as if a part of her brain could still process how impossible the prospect of passing that test was. She saw the life she loved—always on the move—slipping away. I wondered if she was thinking about her sisters and their fate. And I prayed she wasn’t too afraid though I knew she was. Who wouldn’t be?

I stayed up late talking to her. She was too mad to say much, as mad as I’d ever seen her. She’d thought we were all together because I had come to visit, the returning youngest son. Instead, I’d come to betray her. Eventually I went up to bed but not before being sick. I prayed I’d never have a night as bad as this again.

It didn’t quite end there. Mom fell in with a couple of self-styled Gray Panthers she knew slightly from church. Had they known her better they would have seen her decline—that her counting of the offering basket after Mass, a task she’d done for years, had to be quietly recounted. That the books she shelved as the parish librarian usually had to be reshelved.

Nevertheless, these ladies convinced Mom she was the victim of a terrible injustice at the hands of her unfeeling children. They took her down to the DMV so she could reclaim her right to drive and sideswipe cops. Of course, poor Mom didn’t make it past the first few questions on the written test—this from a woman who skipped two grades and started college at 16. I’m all for advocating for seniors’ rights, but I am still mad at these two women. I hope that someday God removes my festering resentment (but not my car keys).

You have told me similar stories about what seems to be a watershed event in caring for our loved ones with dementia, that time when it is no longer safe for them to drive, and we must step in even if it means taking away some of their freedom. It’s a painful defining point in the course of this horrible disease. Some of you may be going through it now. Know that you are doing the right thing, and you are in my prayers. I would welcome your thoughts and experience on this subject.