February is Black History Month, first held when I was a senior in high school in 1971 and more prevalently when I was in college and grad school. Today the month is widely observed in this country. As a student I learned about pivotal figures in Black history and culture, the legacy of slavery, segregation and Jim Crow, and other realities of the Black experience in America. What does that have to do with life in America today? History doesn’t stop with the past.

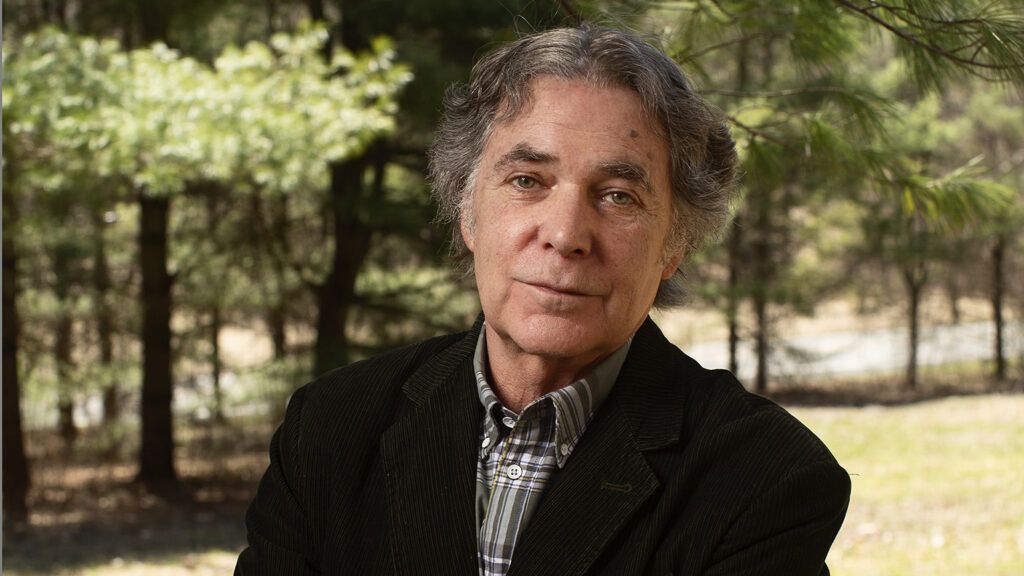

As you may know, I recently published A Journey of Faith, a book for Guideposts about Alzheimer’s, about my family history and my own susceptibility. In my research for the book, I learned so much more than I knew at the outset of this project. One fact that stunned me was the prevalence of Alzheimer’s in the African-American community. By some estimates it is twice the rate than that of the general population, where about one in six people over the age of 65 have some form of dementia. That’s a big number with incredible implications. And considering that two-thirds of Alzheimer’s patients are female, this puts Black women at considerable risk.

At first, I assumed this disparity was simply the result of the distribution of genetic factors. Then I thought about my last visit to my neurologist and what he enumerated as my “protective factors”—among them a high level of education and intellectually challenging work.

If these factors helped protect me against dementia later in life, what does it say about people who haven’t had the advantages and privileges I have?

A lot. Some of the same underlying conditions that put certain populations at higher risk for severe Covid—diabetes, hypertension, obesity—are also risk factors for Alzheimer’s. It is not exclusively a disease that strikes people randomly later in life. Researchers believe that stress itself can make one more susceptible to dementia. Stress hormones affect the brain in ways that may make it more susceptible to brain disease and if you already have a genetic predisposition, that risk factor goes up. Poverty and discrimination are certainly contributors to chronic stress.

For a variety of reasons, among them access to quality healthcare and healthy food sources plus socioeconomic status, including level of education, African-Americans are more likely to fall prey to certain factors that in turn may make them more vulnerable to Alzheimer’s. This relates to Black history because many of the conditions that increase that vulnerability are rooted in the centuries-long struggle for equal rights. History shapes the present, especially Black history in America.

Of course, many of the so-called lifestyle diseases mentioned above generally afflict lower income people of all races, and there is research under way to see how this plays out across the population when it comes to brain diseases like Alzheimer’s. Yet isn’t it reassuring that education, better health care and improved nutrition could help reduce the occurrence of a disease that is expected to extract 1 trillion dollars annually from the U.S. economy in the coming decades as the population grows older?

Here’s another interesting fact: Once an African-American is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s there are studies that suggest they decline more slowly. I have a theory about this. Some research shows that faith and, in particular, participation in faith-based communities and social networks like churches slows the progression of Alzheimer’s.

Regular church attendance is higher among African-Americans than it is in the general population. For centuries the church has been the center of African-American life, especially when white institutions barred Black participation. Ironically that history may pay dividends today when it comes to dementia. In this case, faith can be the great equalizer.

Black History Month is more than the celebration of Black heroes whose courage and sacrifices paved the way for the gains African-Americans have seen since emancipation. It helps us understand the present in many important ways, wouldn’t you agree?