Faces were grim on Engine Company 208.

We sped through the streets of Mesa on our way to one of the worst calls a firefighter can get. “Med-3 on North Rosemont,” the dispatcher’s voice had said. “Possible pediatric drowning.”

The house where a little girl had tumbled into a swimming pool was only three and a half miles from the station. The four-minute drive felt like forever.

We were experienced firefighters. Between the five of us we had nearly 80 years’ experience. This was my sixteenth year with the Mesa department. I knew all too well the awful truth about kids who fall into swimming pools—few survive. It takes only minutes for an oxygen-starved body to shut down. By the time paramedics reach the scene victims usually show no sign of life.

I’d been called to more than a dozen pediatric drownings. Not a single child recovered. A few revived with catastrophic brain damage. Most died.

I reviewed our treatment protocols. First we insert a tube down the victim’s throat and pump it with pure oxygen. Then we establish an IV and administer drugs to strengthen cardiac contractions, all in hopes of restoring oxygenated blood flow.

I tried to stay focused, but my mind kept flitting back to my own kids, who’d grown up just blocks away from the house where we were now headed. Jason and Shannon were teenagers now, but I still saw their faces every time an emergency involved kids.

The worst part was talking to the victim’s parents. I remembered one call, a three-year-old who’d wandered into a neighbor’s backyard and fallen into a pool. The boy’s mother was a friend of our family’s. Her distraught face burned in my memory. I’d felt so helpless, so frustrated that there was nothing we could do. It’s the worst feeling a paramedic can have.

The truck halted in front of a two-story house with a desert garden. A cluster of neighbors stood out front. We hurried inside, lugging oxygen tanks and equipment. My eyes took in kids’ toys on the living room floor, a family portrait photo on the wall. I wondered if the baby in the photo was the child we were about to try to save.

More people clustered in the backyard near a swimming pool. A man on his knees frantically pumped the chest of a tiny girl. She looked about two years old. We raced over. The girl was motionless. Her skin was deathly pale, her lips and fingernail beds a purplish blue—all signs of severe oxygen deprivation. Her shoulder-length brown hair streamed wetly from her head. She wore shorts and a T-shirt.

I pulled the man away from the girl’s body. We inserted the tracheal tube, pumped it with oxygen, administered medication and hooked up a heart monitor. I looked for the parents. They were obvious by their horrified faces. The father, who’d administered CPR, clutched his wife.

They spoke in anguished bursts. The girl’s name was Paisley Walker. Her parents were Terry and Kaye. She was almost two, her birthday just a week away. The family—they had six kids—had only recently moved.

“We were about to put up a fence surrounding the pool,” Terry said.

“Paisley must have wandered outside and fallen in,” said Kaye.

“Please save her!” they both pleaded. I yearned to tell them their daughter would live, but I didn’t dare raise false hopes. I’d seen too many victims rally only to die moments later or live on in a coma. Instead I walked Terry and Kaye through our treatment procedures, keeping them focused on something tangible.

One of the paramedics at Paisley’s side spoke. “We have a pulse,” he said in the measured tone that comes from years of experience.

“She has a heartbeat,” I relayed to Terry and Kaye. “We’re going to medevac her by helicopter to a trauma center in Phoenix.”

Word came over the radio that the helicopter had landed in a nearby field. An ambulance arrived and we hoisted Paisley onto the stretcher, her little body so light and easy to lift. The stretcher wheeled through the house and disappeared inside the ambulance, which sped to the helicopter. I gave Paisley’s parents directions to the hospital and returned to the backyard to help pack up equipment.

A television news reporter hurried up to me. “Will the girl live?” she asked. I thought a moment. “I don’t want this on the record,” I said, “but I don’t think it’s going to be a real good outcome.”

I tried not to think about Terry and Kaye getting the likely pronouncement at the hospital—that Paisley hadn’t made it after all, or that she’d live, but not as the Paisley they’d come to know and love. It was a somber ride back to the station.

My job was finished, but I knew I’d never forget that little girl and how we’d probably failed to save her. I still felt so helpless I didn’t know if I could face another emergency call, whatever it might be. But you have to face it, I told myself as we pulled back into the station. That’s your job.

A week later on a brilliant June morning the guys and I were taking a break when a knock came at the station door. It was Terry and Kaye Walker. The anguished expressions I remembered were gone, replaced by excited smiles. I looked down. At their side stood a little brown-haired girl staring up at me with wide, shy eyes.

“Guys, come here!” I shouted, hardly believing what I was seeing. The guys crowded around and we welcomed the Walkers inside. It was as if nothing had happened to Paisley. She immediately began toddling around the station, marveling at her reflection in the fire engine’s chrome bumper and grabbing every piece of equipment she could reach.

“It’s Paisley’s birthday,” Terry said. “We wanted to stop by and thank you.”

“We wouldn’t be celebrating today if it wasn’t for you,” Kaye said.

I stared at them, then at Paisley. The Walkers kept thanking us, telling how Paisley had revived at the hospital and come home seemingly unscathed a few days later.

I thought of all the other drowning calls we’d been on, all the heartbreak we’d endured at the station. I thought of the grim feeling inside the truck as we’d pulled up in front of Paisley’s house.

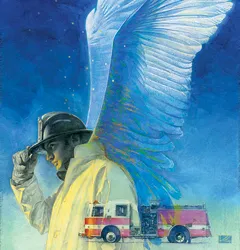

Who’d saved whom? I wondered. Sure, we’d helped save Paisley’s life. But she’d saved us too. She was like an angel fluttering down from God to remind us why we did the work we do. To remind us never to give up hope, even when the odds seem so terribly stacked against us.

It’s been 10 years since Paisley toddled through our station door. We’ve celebrated every birthday with her. Watching her grow into a young lady with a bright future, I feel like I’m watching a miracle of God unfold in real time.

A miracle for Paisley—and for five grim-faced firefighters on Engine Company 208.