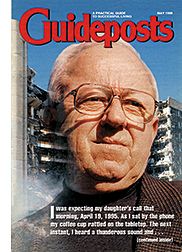

I was expecting my daughter’s call that morning, April 19, 1995. As I sat by the phone, my coffee cup rattled on the tabletop. The next instant, I heard a thunderous sound and the floor shook beneath my feet. I ran to the kitchen window. Blue sky, spring sunshine. A peaceful Oklahoma day. It was hard to imagine anything terrible happening on a bright Wednesday like that.

I hadn’t put on my Texaco uniform that morning; I was meeting my 23-year-old daughter, Julie, for lunch. Proud of her? Everyone who came in for an oil change heard what a great kid I had. She’d caught me bragging on her just two days before. “Dad! People don’t want to hear all that!”

Odd, that visit…Julie often stopped by my service station for a few minutes on her way home from her job at the Murrah Building in downtown Oklahoma City. (Her mother and I were divorced.) Monday, though, it was as if… she didn’t want to leave. She stayed two hours, then threw her arms around me. Julie always gave me a hug when she left, but Monday she held me a long time.

“Good-bye, Daddy,” she’d said.

That was odd too. Nowadays Julie called me Daddy only when she had something really important to say to me. Well, maybe she’d tell me about it that afternoon. Every Wednesday, I would meet Julie for lunch at the Athenian restaurant across from the Murrah Building.

issue of Guideposts

At nine o’clock, I’d sat down with that cup of coffee to wait for her call. Julie usually got to work at the Social Security office where she was a translator at 8 a.m. sharp. It was her first job after college. As a federal employee, Julie got only 30 minutes for lunch—and she wouldn’t take 31! She always called to find out what I wanted for lunch, then phoned our order in to the Athenian so we could eat as soon as we arrived.

Chicken sandwich this time, I’d decided. The parking lot would be full by lunchtime; I’d see Julie’s red Pontiac in her favorite spot beneath a huge old American elm tree. I’d park my truck at one of the meters on the street and watch for her to come out of the big glass doors—such a little person, just five feet tall (“Five feet one-half inch, Dad!”), 103 pounds.

But a big heart. I believed in loving your neighbor and all the rest I heard in church on Sundays. But Julie! She lived her faith all day, every day. Spent her free time helping the needy, taught Sunday school, volunteered for Habitat for Humanity—I kidded her she was trying to save the whole world single-handed.

The rumbling subsided. Bewildered, I stood staring out the kitchen window. Then the phone rang. I grabbed it.

“Julie?”

It was my brother Frank, calling from his car on his way out to the family farm where we’d grown up. “Is your TV on, Bud? Radio says there’s been an explosion downtown.”

Downtown? Eight miles away? What kind of explosion could rock my table way out here! On the local news channel, I saw an aerial view of downtown from the traffic helicopter. Through clouds of smoke and dust the camera zoomed in on a nine-story building with its entire front half missing. An announcer’s voice: “…the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building…”

Floors thrusting straight out into space. Tangled wreckage in rooms with no outer wall. And in place of those big glass doors, a mountain of rubble three stories high.

I didn’t move. I scarcely breathed. My world stopped at that moment. They were appealing for people not to come into the downtown area, but nothing could have pulled me away from the telephone anyway. Julie would be calling. Her office was at the back of the building, the part still standing. Julie would find her way to a phone and dial my number.

All that day, all that night, all the next day and the next night, I sat by the phone, while relatives and friends fanned out to every hospital. Twice the phone rang with the news that Julie’s name was on a survivor’s list. Twice it rang again with a correction: The lists were not of survivors, but simply of people who worked in the building.

Friday morning, two days after the explosion, I gave up my sleepless vigil and drove downtown. Because I had a family member still missing, police let me through the barricade. Cranes, search dogs and an army of rescue workers toiled among hills of rubble, one of them a mound of debris that had been the Athenian restaurant. Mangled automobiles, Julie’s red Pontiac among them, surrounded a scorched and broken elm tree, its new spring leaves stripped away like so many bright lives.

Julie, where are you? Rescuers confirmed that everyone else working in that rear office had made it out alive. The woman at the desk next to Julie’s had come away with only a cut on her arm. But, at exactly nine o’clock, Julie had left her desk and walked to the reception room up front, to escort her first two clients back to her office.

They found the three bodies Saturday morning in the corridor, a few feet from safety.

From the moment I learned it was a bomb—a premeditated act of murder—that had killed Julie and 167 others, from babies in their cribs to old folks applying for their pensions, I survived on hate. When Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols were arrested, I seethed at the idea of a trial. Why should those monsters live another day?

Other memories blur together… Julie’s college friends coming from all over the country to her funeral. Victims’ families meeting. Laying flowers on my daughter’s grave. No time frame for any of it. For me, time was stuck at 9:02 a.m., April 19, 1995.

One small event did stand out among the meaningless days. One night—two months after the bombing? four?—I was watching a TV update on the investigation, fuming at the delays, when the screen showed a stocky, gray-haired man stooped over a flower bed. “Cameramen in Buffalo today,” a reporter said, “caught a rare shot of Timothy McVeigh’s father in his…”

I sprang at the set. I didn’t want to see this man, didn’t want to know anything about him. But before I could switch it off, the man looked up, straight at the camera. It was only a glimpse of his face, but in that instant I saw a depth of pain like—

Like mine.

Oh, dear God, I thought, this man has lost a child too.

That was all, a momentary flash of recognition. And yet that face, that pain, kept coming back to me as the months dragged on, my own pain unchanged, unending.

January 1996 arrived, a new year on the calendar but not for me. I stood at the cyclone fence around the cleared site of the Murrah Building, as I had so often in the previous nine months. The fence held small remembrances: a teddy bear, a photograph, a flower.

My eyes traveled past the mementos to the shattered elm tree where Julie had always parked. The tree was bare on that January day, but in my mind I saw it as it had looked the summer after the bombing. Incredibly, impossibly, those stripped and broken branches had thrust out new leaves.

The thought that came to me at that moment seemed to have nothing to do with new life. It was the sudden and certain knowledge that Timothy McVeigh’s execution would not end my pain. The pain was there to stay. The only question was what I would let it do to me.

Julie, you wouldn’t know me now! Angry and bitter, hate cutting me off from Julie’s way of love, from Julie herself. There in front of me, inside that cyclone fence, was what blind hate had brought about. The bombing on the anniversary of the Branch Davidian deaths in Waco, Texas, was supposed to avenge what McVeigh’s obsessed mind believed was a government wrong.… I knew something about obsession now, knew what brooding on a wrong can do to your heart.

I looked again at the tenacious old elm that had survived the worst that hate could do. And I knew that in a world where wrongs are committed every day, I could do one small thing, make one individual decision, to stop the cycle.

Many people didn’t understand when I quit publicly agitating for McVeigh’s execution. A reporter interviewing victims’ families on the first anniversary of the bombing heard about my change of heart and mentioned it in a story that went out on the wire services. I began to get invitations to speak to various groups. One invitation, in the fall of 1998, three years after the bombing, came from a nun in Buffalo, New York. Buffalo…what had I heard about that place? Then I remembered. Tim McVeigh’s father.

Reach out. To the father of Julie’s killer? Maybe Julie could have, but not me. Not to this guy. That was asking too much.

Except Julie couldn’t reach out now.

The nun sounded startled when I asked if there was some way I could meet Mr. McVeigh. But she called back to say she’d contacted his church: He would meet me at his home Saturday morning, September 5.

That is how I found myself ringing the doorbell of a small yellow frame house in upstate New York. It seemed a long wait before the door opened and the man whose face had haunted me for three years looked out.

“Mr. McVeigh?” I asked. “I’m Bud Welch.”

“Let me get my shoes on,” he said.

He disappeared, and I realized I was shaking. What was I doing here? What could we talk about? The man emerged with his shoes on, and we stood there awkwardly.

“I hear you have a garden,” I said finally. “I grew up on a farm.”

We walked to the back of the house, where neat rows of tomatoes and corn showed a caring hand. For half an hour, we talked weeds and mulch—we were Bud and Bill now—and then he took me inside and we sat at the kitchen table, drinking ginger ale. Family photos covered a wall. He pointed out pictures of his older daughter, her husband, his baby granddaughter. He saw me staring at a photo of a good-looking boy in suit jacket and tie.

“Tim’s high school graduation,” he said simply.

“Gosh,” I exclaimed, “what a handsome kid!”

The words were out before I could stop them. Any more than Bill could stop the tears that filled his eyes.

His younger daughter, Jennifer, 24 years old, came in, hair damp from the shower. Julie never got to be 24, but I knew right away the two would have hit it off. Jennifer had just started teaching at an elementary school, her first job too. Some of the parents, she said, had threatened to take their kids out when they saw her last name.

Bill talked about his job on the night shift at a General Motors plant. Just my age, he’d been there 36 years. We were two blue-collar joes, trying to do right by our kids. I stayed nearly two hours, and when I got up to leave, Jennifer hugged me like Julie always had. We held each other tight, both of us crying. I don’t know about Jennifer, but I was thinking that I’d gone to church all my life and had never felt as close to God as I did at that moment.

“We’re in this together,” I told Jennifer and her dad, “for the rest of our lives. We can’t change the past, but we have a choice about the future.”

Bill and I keep in touch by telephone, two guys doing our best. What that best will be, neither of us knows, but that broken elm tree gives me a hint. They were going to bulldoze it when they cleared away the debris, but I spearheaded a drive to save the tree, and now it will be part of a memorial to the bomb victims. It may still die, damaged as it is. But we’ve harvested enough seeds and shoots from it that new life can one day take its place. Like the seed of caring Julie left behind, one person reaching out to another. It’s a seed that can be planted wherever a cycle of hate leaves an open wound in God’s world.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.