It wasn’t a great summer. I’d been feeling haunted by intimations of my own mortality, unusual for me, who had always seen every day as a gift from God, something to be treasured. But then last summer I fell into an unaccountable funk.

Perhaps it was because I was worried about my mom’s health. A naturally sunny-tempered soul, she’s blessed with what C.S. Lewis once called, in reference to his own mother’s family, “the talent for happiness,” but she’d been hampered by a nagging illness.

In the early part of summer, my wife, Carol, and I joined her for our traditional week in a beach rental, and she couldn’t do the usual walks along the boardwalk or swims out to the buoy that always sustained us. She’s not going to be around forever, I reminded myself.

READ MORE: MOURNED BY HEAVENLY ANGELS

Then, too, maybe I was thinking about own approaching sixtieth birthday. All of a sudden that number started looking very large, in spite of my feeling about half that age. I kept hearing in my head the mournful response Padre Pio is supposed to have given a woman who asked for his blessing at a similar milestone birthday: “Death is not far behind.”

It irritated me that death had taken on such a dark tone when what I’d observed was closer to the “direct flight” an elderly friend said she prayed for. At my own dad’s death just a few years earlier, we had all gathered around his bed those last few days and told wonderful stories, and laughed a good deal too. “He gave us the luxury of saying goodbye,” was how Mom put it.

So why the heaviness in my soul? Why couldn’t I feel that ease I felt at Easter when we sang “alleluias” and hymns that proclaimed, “The powers of death have done their worst/But Christ their legions hath dispersed/ Let shout of holy joy outburst”? Where were those dispersing powers now when I needed them?

We were slated to spend a long weekend at Martha’s Vineyard to celebrate Carol’s college roommate’s sixtieth birthday. “I need to visit a cemetery while we’re there,” I told Carol, an odd sort of outing considering my mood. “I’ve got some long-gone ancestor buried there.”

I’d never been much of a genealogist and had only been able to trace back my father’s family four generations, when a Guideposts reader with the same last name contacted me and asked, “Is it possible that we’re related?” I sent him a note, revealing the extent of my ignorance.

To my amazement he wrote back explaining that we were sixth cousins and sent along a notebook tracing our genealogy back to Puritan days. We were all descended from one James Hamlin, who was brought to the colonies as a baby in the 1630s and lived an astonishingly long time, dying on Martha’s Vineyard in 1718.

His parents had made the trek for religious freedom and his descendants were almost as numerous as the angels above.

My sixth cousin included photographs he had taken, including a gravestone with a dour skull and some words: “Here lieth the body of Mr. James Hamlin late of Barnstable who died at Tisbury May 3rd 1718 in the 82nd year of his age.”

“Now, just how do you think you’re going to find that?” Carol asked.

“It’s on Martha’s Vineyard, somewhere.” I logged on to websites, found the cemetery, but there was no map of where my ancestor’s grave might be, and I could imagine tromping through weeds and brush, looking for some dark stone buried in some deep corner.

On Saturday morning when Carol and her roommate, the birthday girl, were driving to the farmer’s market, they agreed to drop me off at the cemetery for my fool’s errand.

The cemetery didn’t look very promising, a scattering of a hundred stones amid a grassy field. No map, no caretaker’s cottage, no historic plaque, just dark stones, many of them unreadable.

“Where exactly will we find you?” Carol asked.

“Somewhere out there,” I gestured to the field. “I’ve got my phone. You can call.” I was certainly going to need some heavenly help to find Mr. James Hamlin.

And yet, I hardly had to turn around. His stone was right there, just off the road, as though he were looking for me. The bright August sun shone on it like a beacon and the words were clear and easy to read. He’d been here for almost 300 years and with all the changes in the world—cars, cell phones, the internet—nothing much had changed for him, his body at rest.

I lay back in the sunshine. I thanked God for the day and for my life and for all those I loved. Life is short indeed and none of us have that much time on the earth, and yet instead of finding that thought morbid and depressing I found it freeing.

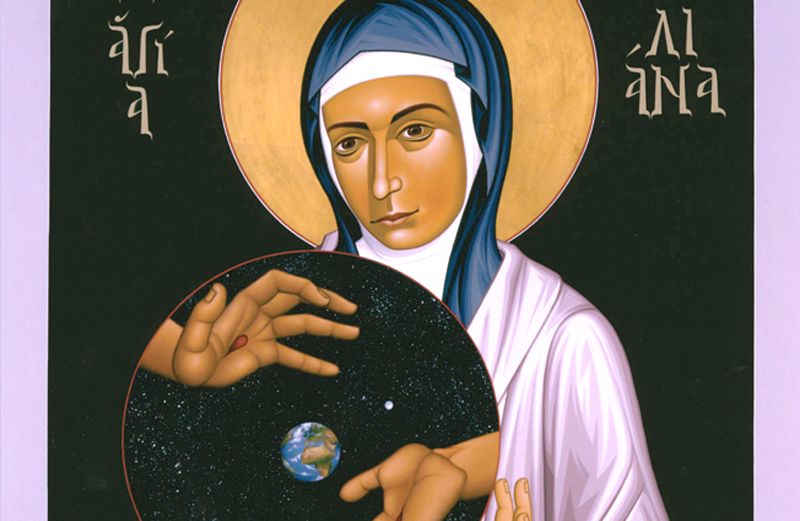

It was a good thing to hold death in mind, like the Puritans did with their carved skulls. Makevthis life count, do all the good you can in the years you have been given, but never forget the angel wings.

The white trail of a distant jet marked the blue sky. A direct flight, I thought. I’d pray for that when the time came.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Angels on Earth magazine.