The bulldozer drove back and forth over the mountain of photographs–several hundred thousand dollars’ worth, more than a decade of my hard work. I stood at the Fort Myers, Florida, county dump, watching it get ground into the dirt. Was this all my whole life really added up to?

Some weeks earlier, on June 15, 1986–Father’s Day–my teenage son, Ted, had been killed by a reckless driver. Nothing had given me a moment’s peace since. Not my wife, Niki, who was lost in her own grief, not my work, not even my faith.

Everything I’d spent my life doing just plain stopped making sense.

For years I’d supported my family as a photographer. Seashores, sunsets, stuff like that. I’d begun taking pictures out of a deep love for God’s natural world, a beauty that nourished my soul, but soon that was swallowed up by the concerns of making a living.

I’d set up my camera, and instead of marveling at what God had created, I’d be calculating how many prints of the scene I would sell.

Not that Niki and I were up to doing much of anything, but this show was part of the routine in my line of work, a long-standing business commitment.

We’d set up our booth as usual, with all the popular scenic shots out front. I went through the motions, chatting with customers. Once they left, though, I sank into my chair, the emptiness in my heart overwhelming me again.

God, where is the beauty in a world where my son could die so senselessly?

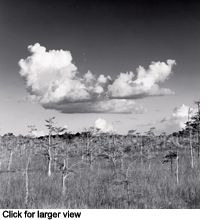

My eye traveled to the half-dozen “art shots” I’d relegated to the rear of the booth. Black-and-white photos of the Everglades that I’d been experimenting with. Niki and I had driven through the area countless times.

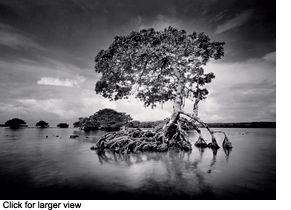

From the car, the Everglades hadn’t looked like much, a featureless sea of sawgrass taking up space between the crowded beaches and tourist attractions. Nothing to take pictures of, I’d thought, until Tom Gaskins, a real Florida old-timer, and Oscar Thompson, a fellow photographer, convinced me to get out of my car and get my feet wet.

A whole other world, really, I thought, sitting there at the art show. Untouched, mysterious, profoundly peaceful, like it had come fresh from God’s hands.

All at once I knew what I wanted–no, needed–to do, for myself and for my grief.

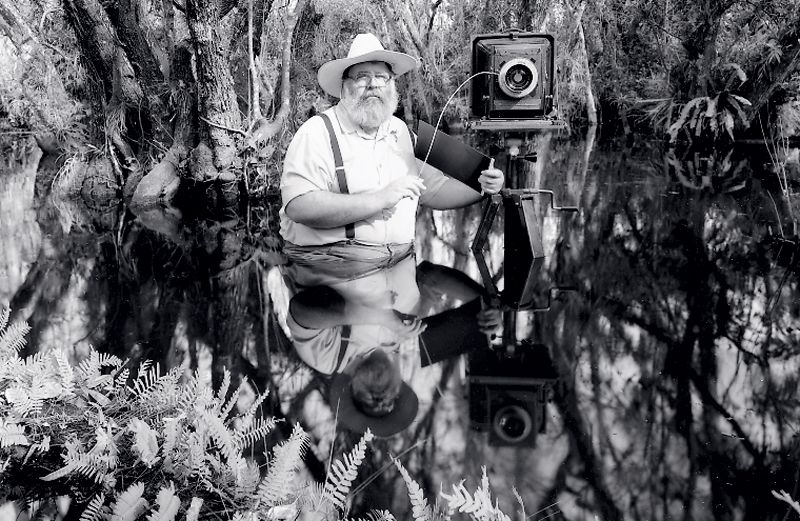

As soon as we returned to Florida, I bought another camera–a bulky, old-fashioned 8-by-10 view camera with accordion-pleated bellows and all. It took large-format film that needed to be loaded shot by shot in big, black plastic film holders. Time-consuming, but perfect for high-definition black-and-white shots.

The next morning I loaded our van with my entire inventory of stock color prints and took them to the dump, where I watched the bulldozer flatten the mountain of photographs. I felt an unexpected sense of release. It was time to start over.

I drove home and called my friend Oscar. I asked if he wanted to help me take some pictures out in the swamp. “These are going to be different,” I said.

“Different how?” Oscar asked.

“I’m not sure,” I said. “I just know I’m supposed to do this.”

Late that afternoon, with my new large-format camera and a stack of black-and-white film in the backseat, Oscar and I drove out to one of the old oil roads that cut through the Everglades. I pulled over, hefted the camera onto my back and climbed into the swamp, Oscar behind me carrying the film.

Water soaked through my shoes and up my legs. I looked at the sweeping expanse of water, trees and sky. I could feel something happening. A picture was coming together, and I’d been drawn here, to this exact place, to take it.

Off in the east, the moon was just rising over a distant line of cypress trees. A huge single cloud began floating across the horizon, almost like wings, straight toward the spot where the moon was coming up. I set up the big camera and waited, letting the stillness of the swamp settle over me. In a few minutes, moon and cloud aligned. Perfect.

Oscar handed me a film holder. I slid it into the camera and tripped the shutter.

Nothing happened. The shutter was stuck. I grabbed another film holder and held it over the aperture for what I guessed was a good exposure time. The spectral moon suspended in the sky, the cloud beneath like a cupped hand waiting to receive it.

Every time I look at that photograph, even now, 18 years later, that stillness, that same mysterious peace, settles over me. I’ve been trying to capture a “moon shot” with the same magic to it ever since.

The timing has never again been as perfect as it was that first moment of my new life, the moment when God drew me back to the wondrous world he created and set me on my way as a photographer again, and to healing.