Harlem's Morningside Park overlooks the brownstones of my historic neighborhood. There's a hill there where I take my problems. Not long ago I stood atop that hill, struggling for a solution to my latest.

I'd had a good year. My wife, Glenna, and I had become parents to twins, a boy and a girl. We lived in a sunny two-bedroom apartment just walking distance from the park. To top it off, I was promoted at work to a managerial position. I felt like I'd really earned it.

I'd always been fairly independent, focusing on my projects until they were the best that they could be. That single-minded determination had paid off. The new position came with a better salary, and our young family's financial life improved greatly. Life was good.

Then the boss called me in for my year-end review.

He shut the door behind me. We sat down. He took a long look at me and read from his evaluation.

"After getting off to a promising start, Kenneth's performance has declined precipitously. He has not demonstrated the qualities of a good leader. He is too immersed in his projects to notice deadlines for his team. His own work takes priority."

My boss looked me in the eye. "You have 60 days to improve," he said. "If you don't, the company will take further action. Up to and including termination."

I left his office in a daze. I had worked hard, and met every deadline. The people on my team were adults. They eventually worked things out and got back on schedule. So what? This was my review. The daze wore off. Now I was mad.

"He straight-up called me selfish!" I told Glenna when I got home. "He said I didn't care enough about the team. I should quit."

"You either find another job in 60 days," Glenna said calmly, "or make this one work."

So I climbed the hill in Morningside Park. "I'm at a loss, God. I need your help." Turning my face to the breeze I whispered, "Help Good Path Elk."

Good Path Elk—my secret name. The one I never used unless I needed direction. I received that name my first summer at Camp Flying Cloud in Vermont, where for two months I was an African-American boy living like a Lakota Sioux Indian.

We slept in tepees, wore loincloths, cooked over an open fire and had powwows.

"You are quiet and strong, and eager to learn," the camp leader said during my naming ceremony. "You are a boy who follows a good path like an elk crossing the woods. Good Path Elk. That will be your name."

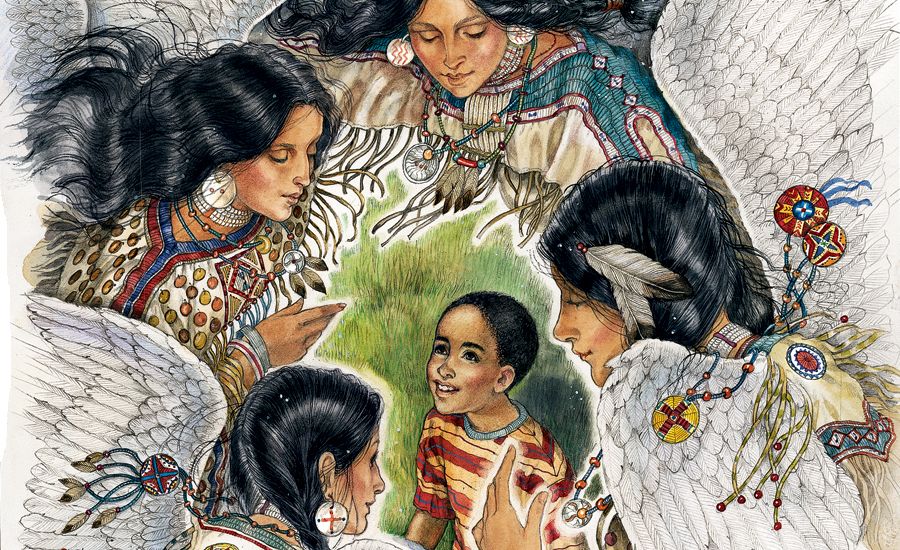

If I was lost, the leader told me all those years ago, I should speak my name to the Four Winds and ask for help. To me, God was the power behind the wind, and those wind spirits were his angel.

I pictured them now, all around me on the hill. "I'm a grown man just as lost as a boy in the woods," I said.

My mind traveled back to a summer day at Camp Flying Cloud. I was 14. My tepee had the chore of cooking that day. But I had a more important task. I was making an Indian warbonnet, one I hoped would be more magnificent than any other.

I'd stitched feathers along the edges of the leather head strap and strung beads to hang down on either side of my face. I even beaded the image of an elk for the front. I was determined to wear my headdress to the powwow that night.

If I worked diligently all afternoon, I could finish it before cooking dinner. I found a comfortable spot up on a hill overlooking a clearing, laid out my materials and got to work.

I heard my friends Rainbow Archer, Smoke Talker and He Dances in the Forest pumping water from the well and carrying it back to camp. I concentrated on stitching the elk on my headdress, right in the center. When I was finished with that I would put a strip of fur on either side, I decided.

I was about to reach for more thread when my counselor called to me on the hill. "Good Path Elk! Food delivery! Our tepee must carry it up from the gravel pits."

Rats! That supply hike was two miles round-trip. I looked around the camp. Almost everyone seemed to have gone off somewhere. The fewer campers to help, the more trips we'd have to make. I'd never finish my headdress in time for the powwow!

"Good Path Elk, let's go!" my counselor called, walking over to me.

"But I swore I'd finish my warbonnet today." My counselor sat down and inspected my work. I could tell he was impressed, and I felt proud.

"It's a good job you're doing," he said. "But you're being selfish."

"No," I said stoutly. "I'm not. I'm being determined."

"You're being selfish," he repeated. "There's nothing more important than doing something for others."

He picked up the headdress. "Crazy Horse. Sitting Bull. Chief Joseph. Those men were warriors. Great men who actually wore bonnets like this. They were great because of the service they provided to their people, not for the glory they brought to themselves.

"If you want people to respect you in this bonnet, you must be deserving of it."

He doesn't understand, I thought. Reluctantly I packed up my materials and followed my counselor down the hill. Truth be told, I followed him because he was the counselor and I had to do what he said. I still thought my work came first.

Now, 25 years later, I stood on another hill thinking it over and feeling every bit as much misunderstood. I thought back on my months as a manager. I worked just the way I always had. Independent. On a schedule. Without much small talk. So why all the complaints?

Then it hit me. Managing the team was my own work. I came down from the hill in Morningside Park knowing what I had to do.

The next morning I went to the office with a different attitude. The one my camp counselor had explained to me all those years ago. If I wanted respect as a manager, I had to earn it.

And my strategy? I would try to see myself providing a service to others. When someone needed help, I had to put aside whatever I was doing to take care of the other person's problem first.

At 5:30, I looked over the day's work coming out of my department. Who needed a gentle push to accomplish more? Who deserved a pat on the back?

My new habits seemed to bring out the best in people. In a way, they brought out the best in me.

By the time my 60 days were up, I wondered if my boss had noticed a difference. He called me into his office and shut the door.

"Congratulations," he said. "I like what I see. You're doing even better than I'd hoped."

On the way home to Glenna that day, I climbed up the hill in Morningside Park. The road before me seemed clearer than ever. I turned my face into the breeze again and whispered, "Thank you from Good Path Elk."