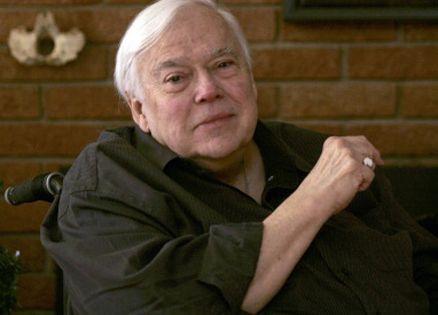

*Reynolds Price passed away on January 20, 2011. We remember him here with this inspiring story.

So far it had been the best year of my life. In love and friendship I was lavishly endowed. I’d recently published my eleventh book. My work had been received more generously than not by the nation’s book journalists and buyers, and for 27 years I’d also taught English literature and narrative writing at Duke University. I’d lived for nearly two decades, alone by choice, in an ample house by a pond and woods that teemed with wildlife; and in February 1984 I’d turned 51, apparently hale.

The previous fall I’d gone with a friend to Israel. It had been my second visit in three years to a place that had fed my curiosity since childhood and was promising now to enter my work. I’d once spent months translating the Gospel of Mark, and I wanted to see for myself the places about which he wrote.

But late in the spring of 1984, tests indicated there was something foreign within my upper spine. Surgery was performed on June 4 and I was under anesthesia for 10 hours. The next morning Dr. Allan Friedman told me he had found a malignant tumor. It was pencil-thick, ten inches long and too intricately braided in the core of my spinal cord to permit him to do more than sample the tissue. I asked how much of it he had removed.

He said, “Maybe ten percent.”

I’ve never known a single hour of doubt that I was made and watched over by the source of all life. But in these early stages of my illness I was at times extremely depressed. From the moment I awoke from the operation, I felt the pain that would become my constant companion.

I now had to face five weeks of intense radiation. A long rectangle was outlined in bold purple dye around my ugly scar, and I was told there was a risk that I might lose the use of my legs. A doctor told my brother my prognosis was “six months to paraplegia, six months to quadriplegia, six months to death.”

And then, on July 3, I had the strangest experience of my life.

I woke at daylight alone in my house, propped on pillows against the head of my old brass bed. No lights were on but I was completely conscious—I’m an easy riser, clearheaded from the moment my eyes click open. I was thinking naturally of the massive violence done to my body, and of all the unknowns that might lie ahead.

Without warning, I was suddenly no longer in my brass bed or even contained in my familiar house. It was barely dawn, and I was lying in modern street clothes by a lake I knew at once. It was the lake of Kinneret, the Sea of Galilee, in the north of Israel—the scene of Jesus’ first teaching and healing. It was the same lake I’d visited the previous October, a 13-mile-long body of fish-stocked water lined with beautiful hills, trees and small family farms.

Still sleeping around me on the misty ground were a number of men in the tunics and cloaks of first-century Palestine. I soon understood with no sense of surprise that the men were Jesus’ 12 disciples and that he was nearby, asleep among them. So I lay on awhile in the early chill, looking west across the lake to Tiberias, a small low town, and north to the fishing villages of Capernaum and Bethsaida. I saw them as they must have been in the first century—stone huts with thatch-and-mud roofs, low towers, the rising smoke of breakfast fires. The early light was a fine mix of tan and rose. It would be a fair day.

Then one of the sleeping men woke and stood.

I saw it was Jesus, bound toward me. He looked much like the lean Jesus of Flemish paintings—tall with dark hair, unblemished skin and a self-possession both natural and imposing.

Again I felt no shock or fear. All this was a normal human event; it was utterly clear and was happening as surely as any experience of my previous life. I lay and watched him walk nearer.

Jesus bent and silently beckoned me to follow.

I knew to shuck off my trousers and jacket, then my shirt and shorts. I followed him.

He was wearing a twisted white cloth round his loins; otherwise he was bare and the color of ivory.

We waded out into cool lake water till we stood waist-deep.

I was in my body but was also watching myself from slightly above and behind. I could see the purple dye on my back, the long rectangle that boxed my thriving tumor.

Jesus silently took up handfuls of water and poured them over my head and back till water ran down my puckered scar. Then he spoke once—”Your sins are forgiven”—and turned to shore again.

I came on behind him, thinking in my standard greedy fashion, It’s not my sins I’m worried about. So to Jesus’ receding back I had the gall to say, “Am I also cured?”

He turned to face me, no sign of a smile, and finally said two words—”That too.” He climbed from the water, not looking round, really done with me.

I followed him out and then, with no palpable seam in the texture of time or place, I was home again in my wide bed.

Was it a dream I gave myself in the midst of a catnap, thinking I was awake? Was it a vision of the sort accorded to mystics through human history? From the moment my mind was back in my own room, no more than seconds after I’d left it, I’ve believed that the event was a gift, a shifting to an alternate time and space in which to live through an act crucial to my survival.

For me the clearest support for my conclusion survives on paper in my handwriting. My calendar notes are sparse—hard happenings only, not thoughts or speculations. And on my calendar for ’84, at the top of the space for Tuesday, July 3, I had drawn a small star and written:

6 a.m.—By Kinneret, the bath, “Your sins are forgiven”—”Am I cured?”—”That too.”

It is the record of an event that had a concrete visual and tactile reality unlike any sleeping or waking dream I’ve known or heard of, and it betrayed none of the surreal logic or the jerked-about plot of an actual dream. The plain fact is that I’ve never since had a remotely similar experience; nor again, had I ever before known anything similar in five decades of a life rich in fantasy.

Over the next five weeks of daily radiation I lay facedown in my body cast while the technician aimed the beam precisely at the target range of my spine; and with my eyes shut I imagined intensely a curative hand laid over my wound, that same hand that had bathed me in Lake Kinneret.

My friend Leontyne Price called. “You’ll be all right,” she said. That was the first arrival, from outside my immediate circle, of a message that came seven more times in the months ahead—the explicit and confident-sounding news that I wouldn’t die, not of this ordeal. Each person wrote or called with no prior collusion—most of them still don’t know each other. One of the strongest assurances came from a woman I hadn’t seen for years, who herself had been stricken with cancer. She phoned and, with no preface, calmly said, “I’ve called to tell you you’re not going to die of this.” Then she quoted the famous talisman lines from Psalm 91: He shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways.

Weakened by the treatments, I went to stay with my cousin Marcia and her husband, Paul. I told Marcia about my morning experience in Kinneret. To please her I sketched a rough likeness of Jesus cupping the water to my head. As I did so, I realized I was suddenly concentrating for more than 10 seconds on something better than the pain that roared down my spine.

The fact of regaining just that much on paper triggered the dozens of drawings I’d make in the next two years. All meditations on the face of Jesus, these drawings became my main new means of prayer. If they asked for anything, I suppose it was what I still ask God for daily—for life as long as I have work to do, and work as long as I have life.

In the spring and fall of 1986 I had more surgeries, to remove tumor tissue that had spread up my back and into my neck. There were times each day, for hours at a stretch, when my whole body felt white-hot pain, scalding and all-pervasive. For three years I took the drugs prescribed to me; and then at Duke Hospital I was taught techniques of biofeedback and self-hypnosis that helped incredibly to ease the searing pain, as well as the self-focus and self-pity that pain eventually clutches to itself.

There have been many moments over these past years when I all but quit and begged to die. Even then, though, I’d try to recall the passage of daunting eloquence in the thirtieth chapter of Deuteronomy: I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live: that thou mayest love the Lord thy God….

Choose life. In my case, life has meant steady work, work sent by God but borne on my own back and on the wide shoulders of friends who want me to go on living and have helped me with a minimum of tears and no signs of pity.

Ten years have passed. Though I make no forecast beyond today, annual scans have gone on showing my spine clear of cancer—clear of visible growing cells at least (few cancer veterans will boast of a cure).

I’m in a wheelchair—I may always be—but I write six days a week, long days that often run till bedtime; and the books are different from what came before. Even my handwriting looks very little like the script of the ravaged man I was in June of ’84. Cranky as it is, it’s taller, more legible, with more air and stride. It comes down the arm of a grateful man.