All my life, it seems, folks have been telling me what I can’t do. In school, my learning disability kept me from picking up things as quickly as the other students. On the playground, I was the biggest, slowest kid. No one thought I could ever be an athlete—except for my mom and dad, who were always telling me that with prayer and persistence I could find the strength to do anything.

Maybe that’s why I was always pushing myself. I found a sport where my 286 pounds were an asset, wrestling, and I took it all the way to the Sydney Olympics in 2000. Naturally I was the underdog, but I made it to the final round and faced the best in the world, the legendary Russian Alexander Karelin, undefeated in 14 years of competition.

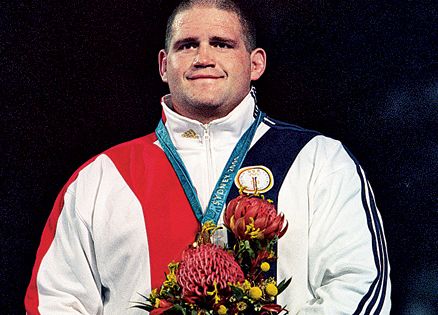

I had an older brother, Ronald, who died when I was eight. I’d win this medal for him. “Rulon doesn’t stand a chance,” the commentators said. “He might as well go home before he gets hurt.” I stood alone on the mat and looked Karelin in the eye. You can do it! I shouted at myself silently. And I did. I beat him. I came back to my parents farm in Afton, Wyoming, with a gold medal and the champion’s belt.

I’d reached the pinnacle, right? But no, I kept looking for new challenges, for other ways to show the world, “Look what I can do!” Afton, in Star Valley, where the Grand Tetons taper into the wooded peaks of the Salt River Range, was just the place for it. I gunned my Jeep around mountain curves, the closer to the edge the better. I raced my four-wheeler through the forests. I pulled stunts with my snowmobile on frozen lakes. I was always testing my limits—and maybe those of the people around me too.

Last February 14, I did my morning workout, then met up with my buddies Danny and Trent for a big lunch. It was about 25 degrees, and the winter sunlight sparkled on the deep snowdrifts that blanketed Afton. “Perfect day for snowmobiling,” I said, pushing my empty plate away. “We’ve got four more hours of sunlight. Who wants to have some fun?” We got our gear and by 1:30 we were roaring through the woods, taking deep gulps of cold air and letting civilization disappear behind us as we climbed into the mountains on our snowmobiles.

Around 3:30, Danny said he’d had enough. “Gotta go. Can’t miss my daughter’s basketball game. Call me later.” Trent mentioned heading in too. “Are you kidding, man?” I exploded. “We’ve still got to tackle Wagner Mountain!”

I revved my motor and shot uphill. The snowmobile slid and I braced with my feet. At the top, I looked over my shoulder for Trent. He was nowhere to be seen. I guess he gave up, I thought. I’ll just take a look around before I turn back. I’d never been up here before. I explored the ridge, loving the spectacular view of Star Valley spreading out below. I called Danny on my cell phone. “I’m on top of the world!” I shouted. “I’ll get Trent and head down in a few minutes. Let’s meet for dinner after the game.”

I swigged the last of my Gatorade and turned back. I found Trent’s tracks and followed them. It was 4:30 now. The sun had started to dip under the ridgeline, casting long shadows on the snow. Man, these are my tracks, I realized, not Trent’s! I took out my cell phone to call him, but now that I was off the peak, I couldn’t get a signal.

I wasn’t far from the Salt River, which winds down into Star Valley, carving a deep gully in the mountainside. I’ll bet he’s checking out the gully, I thought. Its slopes were awesome for snowmobiles. I drove down into the gully. No sign of Trent. The river flows back to Afton, I thought. Might as well follow it home. Trent’ll get back on his own.

I rode alongside the river. A couple places it had overflowed, making semi-frozen waterholes. I tried to cross one. The ice cracked and the rear end of the snowmobile sank underwater. I jumped out, feet soaked. No problem. I could get my snowmobile out. Those things weigh about 600 pounds, but I was strong. I pulled until the sweat was steaming off me. It didn’t budge. I broke off a big tree branch and levered the machine out, and started on my way again.

Another waterhole. Same thing happened, except I ended up soaked to my thighs. Better stick to the slope. It was pitch-dark by now, but I figured I was entering Star Valley. I was bound to see a road soon, then Afton would be a clear shot. I imagined a big steak dinner waiting with a tall glass of Mountain Dew. My stomach rumbled.

The river narrowed and the sides of the gully steepened to almost vertical. I can’t get up that—better just keep going. I inched forward, sending rocks and dirt tumbling under me. Suddenly my snowmobile skidded and slid straight down the slope into the river. I picked myself up, unhurt, but soaked, and stared at the snowmobile on its side in the water. This time I wouldn’t be hauling it out.

The wind cut straight through the fleece jacket I was wearing. Underneath, I had a sweatshirt, T-shirt and runner’s tights—fine for an afternoon ride, but no match for night in the wild. I shivered. I could hear the water sloshing in my boots, but I couldn’t feel my toes. I tried to take the boots off so I could wring out my socks. My fingers were so cold I couldn’t undo the laces. There was a grove of trees nearby. I struggled through waist-deep snow to take shelter.

Still no signal on my cell phone. The clock showed 7:30. Danny and Trent know I wouldn’t miss dinner. I’ll just wait here till they come back for me. I kicked the snow from under a tree and sat down. I felt sore and tired like I’d just wrestled 10 matches in a row. All I wanted to do was sleep. That’s your body shutting down, hypothermia taking over. “Stay awake, Rulon!” I shouted at myself.

I stood up, sat down, pinched myself. I checked my cell phone again: 8:30. What’s keeping those guys? I dozed off, then jerked awake. “Get up! Keep moving!” I yelled again, just like I did on the wrestling mat. But it was no use. One minute I’d be staring up at the bright stars overhead, the next I would wake up spread out on the snow.

My fleece and pants turned into solid ice, my hands froze in my gloves. The next time I checked my phone, it was after midnight. Still seven more hours of darkness! I tried to focus like I would with a tough opponent, like I had with the big Russian. You can do it, I thought. You can do anything, Rulon Gardner!

That’s what my mom and dad raised me to believe, that God hadn’t put me in this world to fail. That’s how I’d lived my life. When my teachers told me I wouldn’t graduate high school, I just worked harder. During my junior year, one teacher said, “Rulon, you may graduate from high school, but forget about college.” Oh, yeah? I thought. I’ll show you. It took me more than six years, but I got my degree from the University of Nebraska. Sports were the same way. I got to the Olympics on my own steam.

“I’m Rulon Gardner,” I shouted at the snowy treetops. “I can do anything!” But my voice was swallowed in the wind.

Around 2:00 a.m. I heard the faint sound of a motor. Trent and Danny! My voice was too weak to holler, so I whistled as loud as I could. The sound came closer, then faded.

They missed me, I thought. No one will find me now. For the first time that night, for the first time in my life maybe, I was scared. I’d worked so hard to get strong, gold-medal strong. I’d tested that strength time and again, often foolishly. Now my strength wasn’t enough. Not near enough. I laid my head against the rough trunk of the tree and closed my eyes. I can lick any opponent, I thought, but this? Lord, I am weak and you are strong. Infinitely strong. Help me.

I drifted off. I dreamed that I was standing in a warm room with Jesus. Beside him was my older brother, Ronald. They were both smiling. I took a step toward them. “Wait, I don’t want to be here,” I said, “not yet.” I woke with a start and struggled to my feet. Overhead the darkness was turning to gray. How much longer until morning? I shut my eyes to pray again. What came to me wasn’t words, but the face of Jesus, like in my dream. In his expression, there was such infinite strength that I felt warmed. My eyes flew open. “I can do this,” I said.

I stumbled back to the river and my sunken snowmobile. I was thirsty, so I bent down and put my lips to the rushing water. It was warmer than I expected, much warmer than the air, so I waded in. I let the water run through my frozen boots and lay back on a rock in the middle of the river, watching the stars melt into dawn. Was that the drone of an engine? I struggled up. An airplane was circling low overhead.

“Hey!” I croaked, waving my arms. The plane dropped something. A heavy coat landed on the snow. I got to my feet and started toward it. Then everything went black.

I awoke to a chopping sound. I was in a helicopter landing at a hospital in Idaho Falls. My core body temperature was 80 degrees, I heard the doctors say. They had to cut my boots off. I was shocked by the sight of my black, swollen feet. Eventually, I lost my middle toe. “You should have lost your feet,” my doctor told me. “In fact, you should have died. The windchill was forty below. Normally, a person can’t survive in those conditions. It’s a good thing you’re so strong.”

All my life I’ve worked hard to get smarter, faster, stronger. But it wasn’t bodily strength that got me through the long, freezing night in the mountains. It was strength from the One who showed me that night what he had been telling me in the classroom, on the wrestling mat…all my life, really: You can do it. The only strength that never fails.