Two weeks. That’s all it was going to be. I was here in Uganda on a mission trip as part of the global justice project at Pepperdine University Law School, where I teach. We’d spend our January semester break helping out some kids who had been stuck in a juvenile detention home, waiting for their day in court. We’d offer legal counsel, prepare briefs to be sent to the judge, do some sightseeing and go home. That seemed like enough of a commitment for someone with my hectic schedule.

My colleague Jay Milbrandt had been urging me to get involved in the global justice program, but I’d put him off. Not only did I have classes to teach but I’m also associate dean of student life, and there was always something coming up. What little free time I had went to teaching Bible classes with my wife at our church or coaching one of our three kids’ soccer teams. Of course I cared about justice, cared very deeply. Justice is the soul of the law. My job was to teach that to my students, not give legal advice in Africa. “Later,” I told Jay.

Then last fall Jay and I went to the annual conference of the Christian Legal Society. Three days of talks and seminars culminated in a closing dinner with Bob Goff, one of the nation’s top litigators, giving the keynote address. Bob’s well over six feet and he towered over the podium, his voice booming as if he were addressing a closing argument to a jury in a murder trial.

“We have a moral, faith-based duty to see that justice is done for the least of us!” Bob talked about the pro bono work he was doing for kids in Third World countries, seeking to protect them from abuses like forced labor and prostitution. Lately he’d been focusing on Uganda where the judiciary was overworked and understaffed, often unable to process the cases of kids who were arrested, some of them with little or no evidence against them. He challenged us to use our legal skills for the poor and oppressed, especially the most vulnerable—the world’s youth.

“Our God is a God of justice,” he declared, then added, “and he’s nuts about kids.”

That final line got me. Something inside me clicked. You could help here, I told myself. Go overseas and use your legal training. It would be a good experience. And a good way to live out your faith. I leaned over and said to Jay, “We’re going to Africa.”

The two of us accosted Bob and asked what we could do. He told us about a children’s prison he’d visited in rural Uganda where children were stuck sometimes for years, their cases unheard, and sometimes used as forced labor. All they needed were a few volunteer lawyers to prepare summary briefs for them so a judge would agree to hear and process their cases. What if a group of us from Pepperdine went there? Bob could put us in touch with the right people.

And so it happened that three months later we were on a plane to Uganda. I had no idea what to expect. I’d been a lawyer for almost 20 years and had clerked for a judge, worked for a large firm and in private practice. I was used to spending months on depositions, but Bob said we could interview the children and learn their cases in a matter of days. All we needed to do was prepare a paragraph-long summary for each child. That would be enough for the judge. A two-week trip, that’s all it was going to be. I could handle it, then be back to my busy schedule at Pepperdine.

We landed in Kampala and drove north to the dusty town of Masindi. We met with a judge and got a list of the 22 cases we’d handle. Finally we were at the remand house, where the children were being held, answering Bob Goff’s call to faith and action. There was no guard or fence around the place, just a few teenagers milling about. Where could anyone escape to, way out here in the bush?

The boys’ hall, where 18 boys lived, was a one-room concrete warehouse. No lights, no screens against malarial mosquitoes, no running water, no electricity, no closets for their clothes, no beds, no privacy whatsoever. Just foam pads and a few ragged blankets. I thought about Bob’s final line, the clincher. How would these kids ever know God was nuts about them?

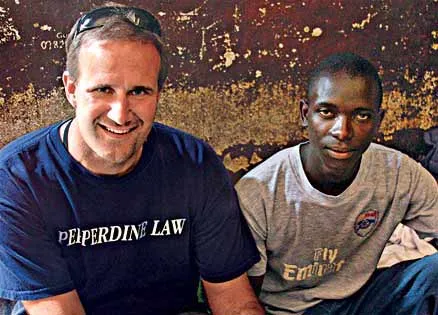

The four of us divided into two groups to interview the kids. “Who can translate into English for these lawyers?” the judge asked. Two young men stepped forward, brothers named Joseph and Henry.

Our group got Henry. A short, slim 16-year-old dressed in sweatpants, a T-shirt and flip-flops, he was bright and deferential, always addressing me as “sir.” We sat down in lawn chairs under a tree. I opened my laptop. What had this sweet boy supposedly done to land here? Steal food for his family?

“Which case is yours?” I asked. He looked over my shoulder and pointed to the screen, “That one…and that one.” I caught my breath. An accused double murderer? I would get to his cases later. First I wanted to clear some of the simple ones.

With each interview I began to see how flimsy the cases were. Some would have been thrown out of court for lack of evidence. I became more and more disturbed the more I found out. I discovered that the matron in charge had unlawfully hired the boys out to local farmers to do forced labor, which was perhaps why their cases had languished so long. One of the boys being forced to work had died of an apparent asthma attack, a heartbreaking miscarriage of justice.

Henry was an excellent assistant, often anticipating our questions. Because of his intelligence and leadership he’d been made the head boy, or “prime minister” as they called him at the house. During a break I gave him my business card and let him listen to my iPod. “What’s the name of that song, sir?” he’d asked. “‘Livin’ on a Prayer’ by Bon Jovi.”

“Ah, a Christian song,” he said. Not exactly, I thought, but the explanation would be too long to go into. Prayer was important to the children. Henry told me they’d prayed after Bob and one of his colleagues had visited them in the fall, asking God to bring the men back to hear their stories and help them. And here we were, an answer to boys’ prayers halfway around the world.

When it came time to interview Henry I sat him down in the lawn chair. “Tell me exactly why you are a prisoner here.”

He and his brother were charged along with others for the murder of a herdsman in their village. They didn’t do it. They couldn’t have. The man was killed between eight and nine in the morning when both were at school. Henry’s teacher confirmed that. But they’d been stuck in this remand house for a year and a half, their education interrupted, their futures on hold indefinitely, perhaps forever, for a case that should have been dismissed in a court of law if it were heard.

The second murder? Because of his position of leadership at the house, Henry was charged along with the matron in the death of the boy who’d died of asthma, something he was hardly responsible for.

The interviews continued. Each night our team stayed up late to write up summaries from our notes, then we went back for more. During one break I took out my phone and showed it to Henry. “This is better than mine, sir,” he said.

“Yours?” I asked. He pulled out his from a pocket. As head boy he was entitled to it. He pointed to the business card I’d given him earlier. Was the phone number on it the number for my cell? No, I said, that was my phone at work. He gestured to my cell again. “What is the number for this, sir?” he said.

I was caught off guard. In an instant I knew that how I answered his question would largely determine what kind of journey I was on. Was I just a do-gooder passing through or someone willing to become personally invested in the life of a 16-year-old Ugandan prisoner? In doing justice where justice was not always done? Was I called to this place because God had moved me or was I just doing something to ease my conscience?

“Of course you can have my number, Henry. I could not have done this work without you and I promise to help you as best I can, through the law and through prayer.” In turn Henry gave me his number. “Thank you, sir.” The deal was sealed. I was in this for the long haul.

I have been back to Uganda three times since that trip in 2010. Henry and Joseph were released, the case against them for the death of the herdsman dismissed. As for the charge against Henry in connection with the boy who died of asthma, I’m working at having it struck from his record when I go back to Uganda this fall. Both boys have since been enrolled in the boarding school Bob Goff started in Uganda, the Restore Leadership Academy. They’re doing great.

Henry calls me on my cell once a week. He always asks, “How’s America?” He asks about my work, my family. He tells me about his school, his family. We discuss the cases of those in the remand house, who’s gone to court and what was decided. This January I’ll head back to Uganda. I’m taking my family with me. I’ll be working with the Ugandan judiciary as part of a six-month sabbatical, and my wife and kids will be working to educate children in the remand home. Did I say two weeks? Did I say I’m as nuts about these kids as God is?

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith.