That June of 2004, out in Portland, Oregon, Mother struggled with pneumonia. This was not the first time she had made the high-speed ambulance ride to the ER, then the gurney trip to ICU, then the slower journey to recovery in the rehab unit of her assisted-living program.

But what could we expect of my 92-year-old mother, Cecilia, a Southern belle from Georgia who had stolen the heart of a Montana man named Herb, our dad, and years later ended up in the Pacific Northwest? She had Parkinson’s disease and a few other senior ailments that seemed to require a multitude of pills. None of this had weakened her spirit.

But now, a week or two into rehab, she needed oxygen constantly. She barely ate. “Just this morning,” the nurse on the phone alerted me, “she’s begun hallucinating. The doctor said it might be the medication.”

READ MORE: THE ANGELS WHO TOOK HER HOME

At the Town Center Village, where Mother lived, she protested when I informed her that the doctor thought she might be having side effects to the medication.

“I am not hallucinating,” she declared from her mound of pillows. Her brown eyes snapped, and I could distinctly hear—despite the plastic nose mask—“I tell you, he’s right there!” She pointed to a spot beside her bed.

“He calls himself Bill,” she announced. “And I think it’s highly inappropriate for a strange man to be in my room! Right next to my bed!”

“Well,” I asked, “is he behaving himself? Has he done anything inappropriate?”

“No,” she admitted.

“Mother, could you describe Bill?”

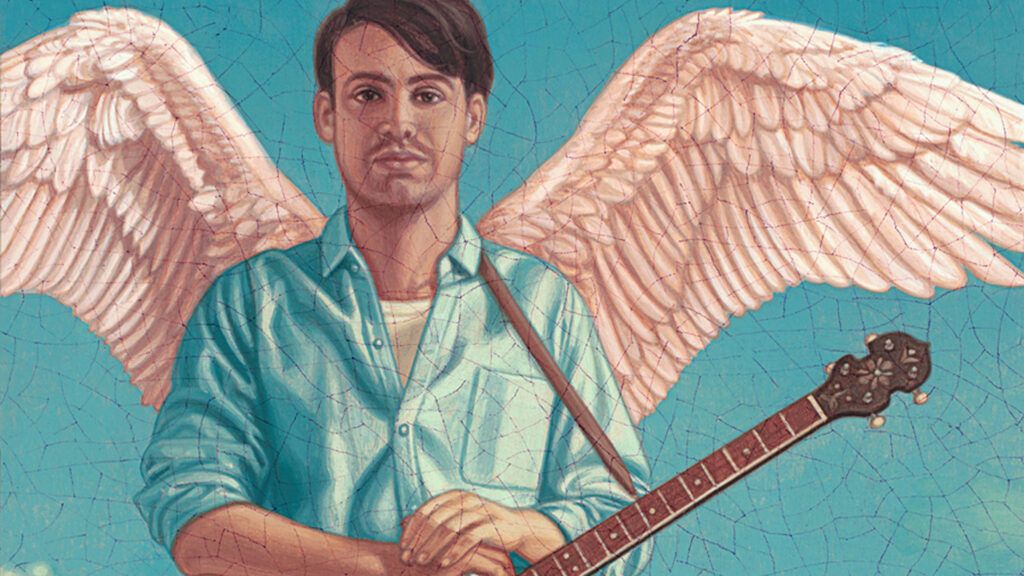

“He’s about thirty years old, medium height with dark hair, and he’s got a banjo,” she said between gasps for air. Mother loved to talk. She could make friends with almost anyone, carry on lengthy conversations with strangers, and no oxygen mask was going to stop her.

“Is he playing the banjo?” I asked, curious.

“No, he just wears it on a strap over his shoulder.”

“Maybe he’s here to help. If he’s not doing any harm, I wouldn’t worry about him.”

And so, as the days passed and Mother’s condition remained serious, we tolerated Bill. I asked her if he talked much.

“No, very seldom,” she replied. “Just sort of stands around?”

“Seems to.”

READ MORE: CHAPERONE TO HEAVEN

There were only a few days that month, two or three perhaps, when Mother mustered her strength to travel by wheelchair to the sitting lounge. Once or twice, we even went outside into the sunlight. The ubiquitous oxygen tank rode with her. And just before leaving her room, Mother would wave good-bye to Bill.

So would I. He remained an invisible mystery to me, but to Mother, a vivid presence. I liked to think a comforting one.

I read to her some, mostly her Bible, sometimes a magazine piece. Those days when she felt strong enough to talk we remembered people long gone and events long over. One afternoon we sat outside in the warm summer air. She looked so small wrapped in a pink cardigan and a couple of blankets.

“I had a dream last night,” she said. “I dreamed about your dad.”

Dad, the tall, silent guy who loved geology and could tell you how to get the ore from rocks, who’d packed into Glacier National Park with horses as a youth and traveled up the Amazon and all over South America as a young man prospecting for American mining outfits. Dad died Christmas Day of 1993, a decade earlier.

“How did Dad look?”

“He looked great, like a young man. He told me we were going on a trip and not to bother to bring any luggage. That was odd, wasn’t it?”

Really odd, I thought. I felt disheartened. I wished she would regain her strength, that vigor that had been such a prominent part of her personality. Daily she seemed to diminish. What was happening to my life-of-the-party mother?

One afternoon she recounted again a story from school days, a memory that always brought chuckles. She and her sister, Eldredge, two years younger, had performed in a play at North Atlanta Presbyterian School. The auditorium was packed with family and friends of the young cast and crew.

All in the audience held their breath as performers came onstage. In the middle of the drama, Mother forgot her lines, except for one, and she turned to her sister Eldredge, her dramatic partner, and repeated over and over, “Let’s get out of here, Bill! Let’s get out of here, Bill!” each time with more intensity, more desperation. The rest of her lines erased from memory.

Finally too embarrassed, both sisters rushed off stage. Later it became an inside joke between them. When together, and in a boring or bewildering situation, one would whisper to the other, “Let’s get out of here, Bill!” and they’d escape, leaving a wake of uncontrollable giggles.

“Bill, that’s the name of your new friend in the room, isn’t it, Mother?” She nodded. Her condition remained grave and she went into hospice, returning to her own room, the home containing her treasures for the past six years. Four days later she slipped away, right before midnight. I watched her go. I’m guessing that her last words, though not out loud, were “Let’s get out of here, Bill!”

The two of them probably burst into laughter. No bags were taken, just one banjo. It was Father’s Day, and I’m guessing Dad must have met them somewhere along the way.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Angels on Earth magazine.