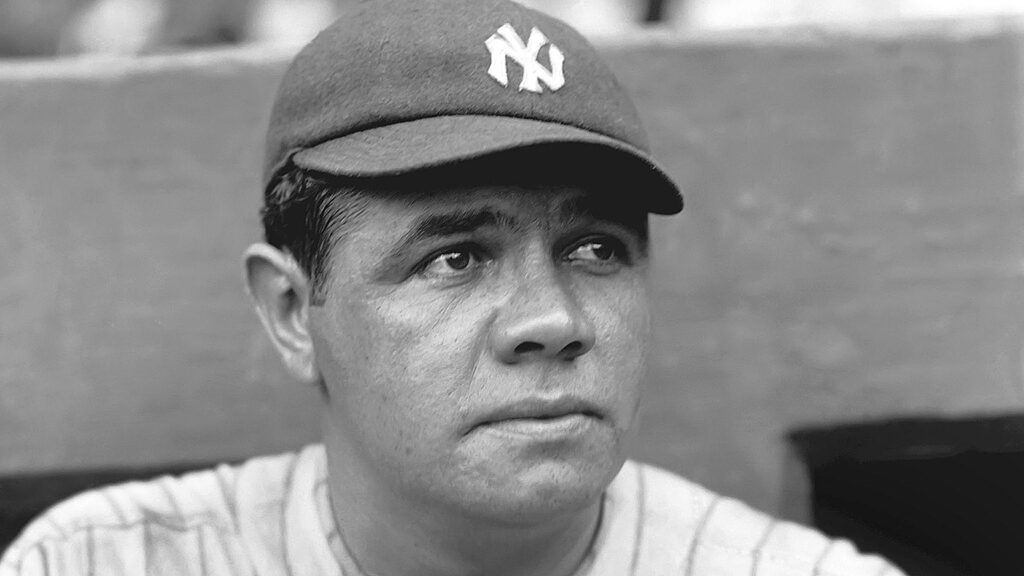

This is Babe Ruth’s last message. It was written with the help of friends Joe L. Brown (of the MGM Studios which produced The Babe Ruth Story), Paul Carey, and Melvyn G. Lowenstein not long before the Babe died. The Guideposts office received it on the fatal day–August 16, 1948.

We bring it to our readers as a notable guidepost to the solution of the serious problem of juvenile delinquency, it is the simple, honest story of a man who relearned what faith meant, and who says so humbly and proudly, knowing it was his most valuable legacy to his fellow man.

Bad boy Ruth–that was me.

Don’t get the idea that I’m proud of my harum-scarum youth. I’m not. I simply had a rotten start in life, and it took me a long time to get my bearings.

Looking back to my youth, I honestly don’t think I knew the difference between right and wrong. I spent much of my early boyhood living over my father’s saloon, in Baltimore–and when I wasn’t living over it, I was in it, soaking up the atmosphere. I hardly knew my parents.

St. Mary’s Industrial School in Baltimore, where I was finally taken, has been called an orphanage and a reform school. It was, in fact, a training school for orphans, incorrigibles, delinquents and runaways picked up on the streets of the city.

I was listed as an incorrigible. I guess I was. Perhaps I would always have been but for Brother Matthias, the greatest man I have ever known, and for the religious training I received there which has since been so important to me.

I doubt if any appeal could have straightened me out except a Power over and above man–the appeal of God. Iron-rod discipline couldn’t have done it. Nor all the punishment and reward systems that could have been devised. God had an eye out for me, just as He has for you, and He was pulling for me to make the grade.

As I look back now, I realize that knowledge of God was a big crossroads with me. I got one thing straight (and I wish all kids did)–that God was Boss. He was not only my Boss but Boss of all my bosses.

Up till then, like all bad kids, I hated most of the people who had control over me and could punish me. I began to see that I had a higher Person to reckon with who never changed, whereas my earthly authorities changed from year to year.

Those who bossed me had the same self-battles–they, like me, had to account to God. I also realized that God was not only just, but merciful. He knew we were weak and that we all found it easier to be stinkers than good sons of God, not only as kids but all through our lives.

That clear picture, I’m sure, would be important to any kid who hates a teacher, or resents a person in charge. This picture of my relationship to man and God was what helped relieve me of bitterness and rancor and a desire to get even.

I’ve seen a great number of “he-men” in my baseball career, but never one equal to Brother Matthias. He stood six feet six and weighed 250 pounds. It was all muscle. He could have been successful at anything he wanted to in life–and he chose the church.

It was he who introduced me to baseball. Very early he noticed that I had some natural talent for throwing and catching. He used to back me in a corner of the big yard at St. Mary’s and bunt a ball to me by the hour, correcting the mistakes I made with my hands and feet.

I never forget the first time I saw him hit a ball. The baseball in 1902 was a lump of mush, but Brother Matthias would stand at the end of the yard, throw the ball up with his left hand, and give it a terrific belt with the bat he held in his right hand.

The ball would carry 350 feet, a tremendous knock in those days. I would watch him bug-eyed.

Thanks to Brother Matthias I was able to leave St. Mary’s in 1914 and begin my professional career with the famous Baltimore Orioles. Out on my own … free from the rigid rules of a religious school … boy, did it go to my head. I began really to cut capers.

I strayed from the church, but don’t think I forgot my religious training. I just overlooked it. I prayed often and hard, but like many irrespressible young fellows, the swift tempo of living shoved religion into the background.

So what good was all the hard work and ceaseless interest of the Brothers, people would argue? You can’t make kids religious, they say, because it just won’t take. Send kids to Sunday School and they too often end up hating it and the church.

Don’t you believe it. As far as I’m concerned, and I think as far as most kids go, once religion sinks in, it stays there–deep down. The lads who get religious training, get it where it counts–in the roots. They may fail it, but it never fails them.

When the score is against them, or they get a bum pitch, that unfailing Something inside will be there to draw on.

I’ve seen it with kids. I know from the letters they write me.

The more I think of it, the more important I feel it is to give kids “the works” as far as religion is concerned. They’ll never want to be holy–they’ll act like tough monkeys in contrast, but somewhere inside will be a solid little chapel.

It may get dusty from neglect, but the time will come when the door will be opened with much relief. But the kids can’t take it, if we don’t give it to them.

I’ve been criticized as often as I’ve been praised for my activities with kids on the grounds that what I did was for publicity. Well, criticism doesn’t matter. I never forgot where I came from. Every dirty-faced kid I see is another useful citizen.

No one knew better than I what it meant not to have your own home, a backyard, your own kitchen and ice box. That’s why all through the years, even when the big money was rolling in, I’d never forget St. Mary’s, Brother Matthias and the boys I left behind. I kept going back.

As I look back those moments when I let the kids down–they were my worst. I guess I was so anxious to enjoy life to the fullest that I forgot the rules or ignored them. Once in a while you can get away with it, but not for long. When I broke training, the effects were felt by myself and by the ball team–and even by the fans.

While I drifted away from the church, I did have my own “altar,” a big window of my New York apartment overlooking the city lights. Often I would kneel before that window and say my prayers.

I would feel quite humble then. I’d ask God to help me not make such a big fool of myself and pray that I’d measure up to what He expected of me.

In December, 1946, I was in French Hospital, New York, facing a serious operation. Paul Carey, one of my oldest and closest friends, was by my bed one night.

“They’re going to operate in the morning, Babe,” Paul said. “Don’t you think you ought to put your house in order?”

I didn’t dodge the long, challenging look in his eyes. I knew what he meant. For the first time I realized that death might strike me out. I nodded, and Paul got up, called in a Chaplain, and I made a full confession.

“I’ll return in the morning and give you Holy Communion,” the chaplain said, “But you don’t have to fast.”

“I’ll fast,” I said. I didn’t have even a drop of water.

As I lay in bed that evening I thought to myself what a comforting feeling to be free from fear and worries. I now could simply turn them over to God. Later on, my wife brought in a letter from a little kid in Jersey City.

“Dear Babe”, he wrote, “Everybody in the seventh grade class is pulling and praying for you. I am enclosing a medal which if you wear will make you better. Your pal–Mike Quinlan.

P.S. I know this will be your 61st homer. You’ll hit it.”

I asked them to pin the Miraculous Medal to my pajama coat. I’ve worn the medal constantly ever since. I’ll wear it to my grave.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.